40 years after Pinochet’s bloody coup, war photographer David Burnett travels back to Chile in search of his most famous subject

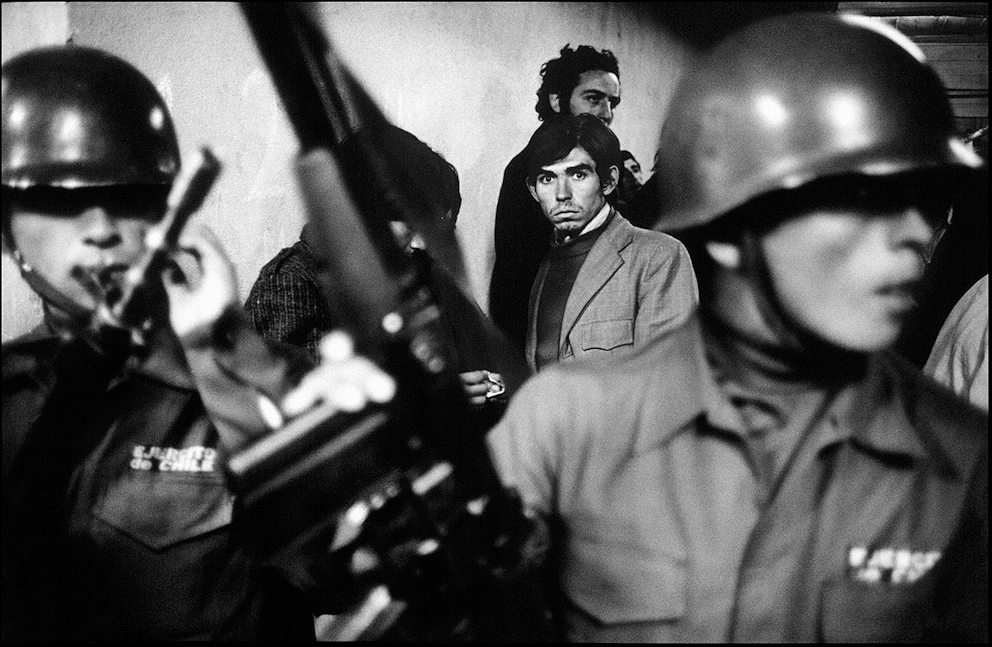

It’s not an image, it’s a mirror. The photograph stares back at you. Framed by blurred rifles and a few distracted compatriots, the man in the middle stands crisply and damns you with his eyes. It’s as if he knows that you are complicit in this thing that is happening to him, in his arrest, the torture, the possibility of his death. Argue if you will, but the fact remains: you are free, he is captive behind the soldiers.

Now imagine that it had been you in the tunnel that day forty years ago, that it was you behind the camera that took that picture. Imagine that it became perhaps your most famous picture in a long career. Imagine that you have spent decades honestly trying to understand what it means to make pictures of people in crisis or in triumph, and that this picture spoke as much about your life’s work as any other.

Wouldn’t you want to know who that man was? Wouldn’t you want to meet him?

David Burnett has spent his whole life in photography. There he was, winking at Gorbachev to try to get an expression. Squaring off with Mondale on a campaign plane. Waiting for just one shot of Mary Decker in agony. Or, in the beginning of his career, shacking up at a $2-a-night flophouse in wartime Saigon, losing friends in that helicopter crash over Laos that killed Larry Burrows, walking that dusty road in Trang Bang where 9-year-old Kim Phuc ran naked after a napalm attack. Dirty wars, famines, presidential palaces. He even covered music some, going on tour with a little-known rocksteady singer named Bob Marley.

It’s tempting to see him as a photographer’s Forrest Gump, crashing all these great moments in the last forty years of history. But he was never—if you’ll forgive the expression—just photobombing the shot. He had his own relentless drive to thank for his access. And he was, for much of the time, an emissary of the greatest news magazine in its prime, in the era when Time Magazine would throw its editors and publishers on a chartered plane and whisk them across the world for informal sessions with emirs and dictators and plutocrats. David was the guy they took with them.

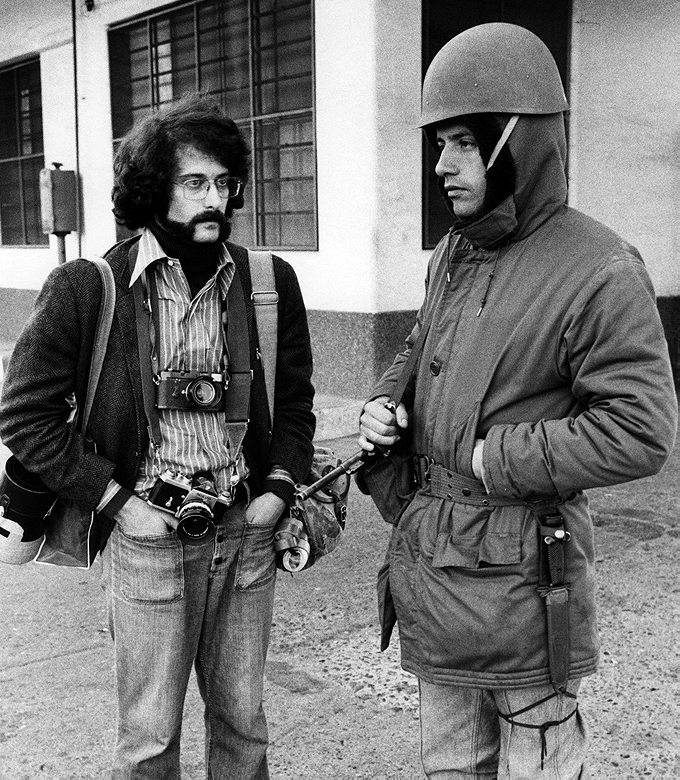

Not that he wears those credentials loudly. Other photographers of his pedigree are scowlers flanked by groveling assistants, but you get the sense that David could hardly intimidate someone even if he wanted to. He makes jokes, does bad impressions, speaks atrocious Spanish and fluent French with equal aplomb. He may be in his 60s, but he still insists on carrying his own gear, no matter how bulky. So when he piles out of his hotel room, he is carrying a box camera the size of an old television, a bat-sized tripod, no less than three cameras around his neck and an oversized double-barreled fanny pack for his slide film. His wears beat-up sneakers and clothes that seem a size too big for him—a cousin of his, having seen him featured on a television news special, ribbed him about having a Hasid for a tailor.

David may be utterly without pretense, but he remains a perfectionist. There is perhaps no one alive today who is better, or faster, with the temperamental Speed Graphic than David. He has that talent that the best photographers have, the ability to see a complete frame in the middle of the chaos of real life.

The moment for photography after the coup was brief and brilliant

That, in a sense, is what has brought him back to Chile 40 years after he first arrived. All careers, even a distinguished one like his, are chaos. What was the purpose? What does it mean to make pictures of history? Is it stenography or something more important? The man in the photo might know.

September 11 in the United States has its own iconic pictures: falling man, burning towers, stunned crowd. They are semaphores for a much deeper pain. Look at them and everything you choose to feel about those days comes flooding back.

Half a world away, Chile has its own iconic imagery of September 11, for a separate anniversary, older but no less painful. Forty years ago today, General Augusto Pinochet overthrew the elected government of Salvador Allende. What had been a tidy, prosperous nation that prided itself (perhaps too much) on its European heritage was plunged into third world chaos. The Air Force bombed La Moneda Presidential Palace, Allende shot himself in his office, and nearly two decades of brutal repression—kidnappings, tortures, disappearances, dictatorship—began.

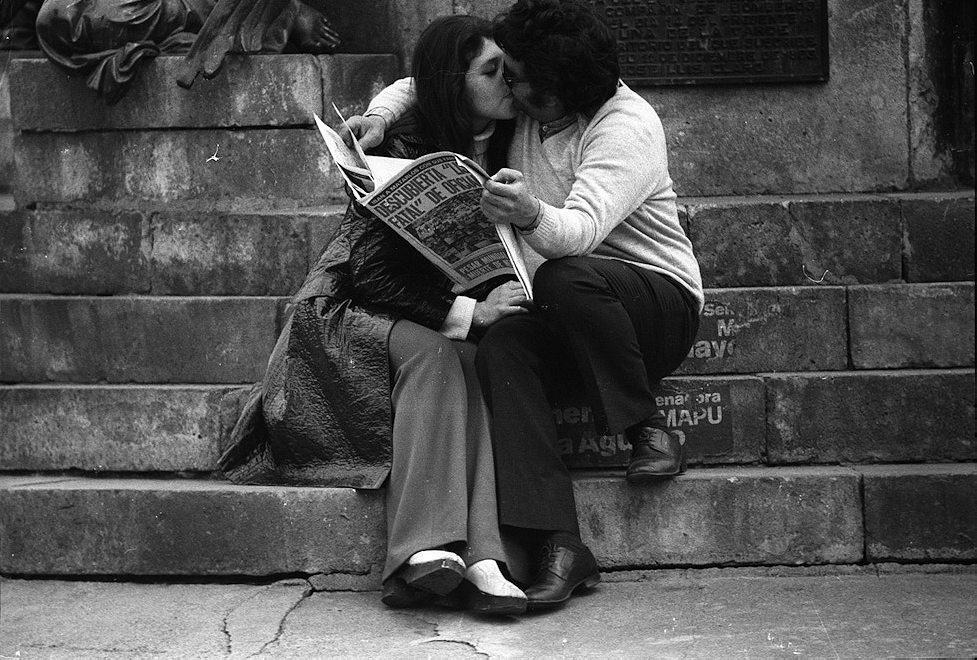

The moment for photography that arose was brief and brilliant. Later on, the regime would control every word, and every image. The debate is still evolving, forty years later, because it was simply disallowed for so long (Chilean President Sebastian Piñera told me in an interview last week that the coup happened in large part because Allende had “no respect for the law”, a statement that has drawn waves of scorn in Chile). The leadup to the 40th anniversary had been an unexpected gutpunch to the city and the country: everyone in the country has been glued to Chilevision’s documentary series Las Imágenes Prohibidas, which showed never-before-seen footage of the coup and the dictatorship. A producer of the series told me it was exhausting, not just the work but the reception. The right feels accused, the left mourns, everyone still argues over why it all happened.

But in the dissolute days just after the coup, there was no debating the sudden violence of the new regime. And photographers—both Chileans and a small group of internationals—were there to document it.

The Man in the Photo, as a Chilean documentary from Maria Jose Martinez calls him, is perhaps the most iconic of all those images. It was widely published throughout Europe at the time, as were several other of David’s images. His work from Santiago became part of a book that won him the Robert Capa award in 1973, the highest prize in overseas news photography. But there was something about the gaze of the man in the photo in particular that gave it an underground afterlife in Chile. It survived and was pirated and reprinted through the years of dictatorship, and when Pinochet stepped down and the still-ongoing process of reckoning began, it gained even more purchase, appearing on album covers and book jackets. The eyes, they say it all to the people who lived through it as the man in the photograph did.

Pin Campaña wants to help. She’s an accomplished photographer in her own right, and an almost tediously moral one. She is working on a multiyear project living with and photographing Chile’s Mapuche people, but she would not, she says, exploit them by actually publishing those pictures.

I, as an American, am more transactional. When we make contact on Facebook, I first offer her money to help us as a fixer, to help us find the man in the photo. She laughs that off and instead messages me an old news photograph of her father as a prisoner, taken in the same stadium where David took his pictures, the National Stadium where the junta kept and tortured and killed its prisoners. “That picture saved my father,” she tells me later. It wasn’t David’s photo, but all the pictures that documented the fact that the regime was holding someone were potential lifesavers. Pinochet was killing his people, but he did not want the world to know, especially not Europe, where the outrage at the putsch was at its sharpest. So there was something like a rule that came to be understood later on: if a photo of you in government custody made it out to the wider world, then you might well be released at some point. It is hard to disappear someone if they are in a photo in your custody.

Campaña’s father had been a leftist newspaperman, and after his captivity they had all been exiled to France. Now her own children are grown, but Campaña can still summon a sultry weariness that would out-Signoret any Parisian. Sitting on a curb, smoking a cigarette after drinks at Liguria our first night in Santiago, she turns to me as if to a child: “Oh, Nathan, you do not understand. Photographers saved lives here.” And then she tells the story of the man who took her father’s picture: when the police came for the photographer himself a short time later, there was no camera there to record it. The photographer was never seen again.

Daniel Céspedes is the name of the man in the photo. And to be truthful, the name had been known for years now. After the dictatorship collapsed, a Chilean paper published his photo and asked for any information about who he was. In a society that could finally talk openly about these things, his name came forward. There was an article, a two-day photo shoot, a mini-documentary that got limited viewers, but that more or less told the story.

Knowing the name did not make the job of finding Daniel now any easier. David had actually been in friendly correspondence on Facebook with Daniel’s daughter Daniela since 2010, and had assumed that she would arrange a meeting when we arrived in Santiago. But when we pressed, she equivocated. In Spanish or in English, she shrank away online, until we were left with nothing.

One possible explanation began creeping into conversations: perhaps he did not want to meet David.

There were theories, expounded in the first few nights in Santiago over beers with photographers or over lunch at the sharp new Museum of Memory dedicated to recording the human rights abuses of the dictatorship. Perhaps Daniel was angry about the documentary. Perhaps he was resentful, thinking that David had gotten rich off of this now-famous image (he had not—most all the reprinting in Chile had been done without permission or royalties). It was certainly true that in order to a do a quick-hit 40th anniversary story, many Chilean media outlets were hounding Daniel for interviews, which could have drove him into a shell. But one possible explanation began creeping into the conversations that was more troubling than the others: perhaps he did not want to meet David. Perhaps this photo had done him harm.

The photo was never supposed to have happened, and David’s recklessness in 1973 was the reason why it did. He was reckless when he came into the country—fresh from Vietnam, he came in with an astounding look, perfect for the half-rebelling US Army and the culture in Saigon, but outright dangerous in Chile. Loaves of thick black hair, an infamous Fu Manchu. A couple days after the coup, David flew in on a chartered plane to a deserted Santiago airport and hitched a ride on a dumptruck into the city, all the while looking like exactly the kind of “extremist” the rightwing military was rounding up throughout the city.

He and most the rest of the international journalists found rooms at the Carrera Hotel, across from the bombed Moneda presidential palace. On his first foray outside the hotel, he made a picture of what looked like a businessman or bureaucrat being led in cuffs to a waiting van. That one made the cover of Paris Match. One of the next trips was to the giant, rusting soccer stadium in the south of the city where he had heard prisoners where being taken. He and a friend, an Miami-based photographer with a shaved head named Bob Sherman, approached an officer outside and asked if they could take pictures. They were ushered inside, down a tunnel, into the bowels of the stadium, and immediately arrested. Cameras taken off their shoulders, made to stand with their hands against the wall. For two hours they were kept at gunpoint there, as the screams of the tortured bounced down the concrete walkways. They were told not to talk, not to look around. But David remembers one thing more than any: a single drop of sweat, forming on the crown of Sherman’s head, forming and then slowly sliding down his forehead, across his brow, down his nose, and then falling free.

“You should have been killed,” says Campaña to this story, and she’s right. Foreigners were not immune to the violence and murder of the coup.

But they were not killed. He and Sherman were released, their cameras even returned. Their U.S. passports may have played some role in this: the CIA was a major author of the coup, and the instability that had preceded it. The junta had but one friend in the world, and it was the U.S. Later, when David and I tour the worst of the torture sites in the stadium—a gruesome locker room where U.S.-trained agents shoved electrodes in the vaginas of political prisoners and drowned them in vats of feces—we hear more about this from Wally Kunstmann, an indomitable woman who was herself a former political prisoner and exile. Kunstmann is now leading the movement to have parts of the stadium preserved as a memorial to all the inhumanity, but it’s not just Chilean opinion she cares about. She nearly comes to tears in that torture chamber when talking about voters in the U.S. May you realize the results of your actions, she says, talking not just about Chile but also Syria and all of the rest of it: Good people died here.

David’s release in 1973 occasioned a strange bit of good. The next day he was back in the stadium, this time as part of a press tour—international media only—to demonstrate the good condition of (some) of the prisoners. The images from that day, from the stands where the prisoners were taken each morning to await interrogation, are strong. But as the press tour was leaving the stadium, David recognized a tunnel he had been taken down the day before. He told the guards that the photographers wanted to go down that tunnel. Everyone stopped. And as the guards tried to figure out how to forestall the strange request, prisoners started coming in: a row of smartly dressed young women with their hands behind their heads, and, eventually, Daniel, who was being shepherded down the narrow tunnel in a group of prisoners, just past David’s camera.

“We weren’t meant to see them,” David tells me, shaking his head at the dumb luck of it all. “No one was supposed to have seen them.”

There were other images, other faces, from David’s 1973 work. David had the idea of meeting more of them, not just Daniel, upon his return to Chile.

This proves far more difficult than expected. The Museum of Memory runs a social media campaign, David goes on CNN Chile and appears in online media making his plea, but too much time has elapsed. After 40 years, many of them are dead, of natural causes, if not dictatorships. Others simply don’t want to be remembered. When we gather a group, with Kuntsmann’s help, of former political prisoners of the stadium for a picture (none had been in David’s original photos), even they had mostly spent the last four decades avoiding returning to the place of their detention. That’s not easy to do when voting stations are in the stadium, when the national team plays all its games there.

Another problem is more technical: like the vast majority of the 3000 or so victims of Chile’s rightwing terror, many of the people David photographed were poor, and the odds aren’t good that they would be lounging around on Facebook or watching premium cable news for signs of their captivity.

There are, however, two whom David has found. One of the most striking moments in the days after the coup was the funeral of poet Pablo Neruda. He died two weeks after Allende, as if from a broken heart, and his procession through the streets of Santiago would be the last public display of the left wing of Chilean politics for nearly two decades. Flanked by glaring soldiers, with the protection only of the foreign press that was there, they actually raised their voices and sang the Internationale, at a time when suspected leftists were being subjected to mock executions and real ones throughout the city. It was, everyone agrees, an astonishing scene.

In the middle of it, two teenage friends—Leila Nash and Amanda Fernandez—walked behind the casket and wept. David’s picture of them from that day is compositionally similar to the one of Daniel: bordered by chaos, the frame’s center is pure and clear emotion. The tears give it a different temperature than Daniel’s picture. But mixed in with the grief is a similar hint of indignation.

Leila and Amanda haven’t seen each other in 38 years, but they have agreed to meet David, and each other, in Santiago. It is the first and perhaps only break for David. Without the people in these pictures, David and photographer Michael Magers, who flew here to document the trip, had been doing the next best thing: photographing the locations where David had been. The cemetery where Neruda was buried, the street in San Borja where policemen burned the books of the arrested, the caverns of the National Stadium where David nearly lost his life 40 years ago.

It is a bright morning when David meets Leila and Amanda at Amanda’s small 6th floor salon in central Santiago. Anyone who should want to know about the beauty and trauma of the Chilean people should have been in that room that morning. The women had met in the early ’70s because they were neighbors, because they were both from leftist families in a rightwing district, because Amanda had a huge crush on Leila’s older brother Michel. For 38 years, life had kept the girls apart—”it was as if all the color had been taken out of the world,” Leila says about life under Pinochet—and now they came together over tea and cookies with the man who took their picture those decades ago. There are hugs, smiles, warm words with David, who makes several stunning images of the two of them together: teary Amanda, stoic Leila.

Then it came out why the two had been in tears back then at Neruda’s funeral. It was not just the collective fear of those days, nor the release of being able to walk freely, just that once, in the streets. Rather, it was Michel. The 19-year-old boy who had captured Amanda’s eye had been conscripted into the army earlier in 1973. When the coup happened, it was known: soldiers from leftist families were being murdered. The armed forces were cleansing their ranks. Michel had gone missing just before the funeral; he was murdered the next Monday. All these years later, his remains haven’t been found. There are still people in government who know more than they are saying about the many murder and burial sites around Chile, but there are no answers for Leila’s family.

Pin Campaña was up till late at night talking with Daniel’s neighbor on the phone. We have been learning more about Daniel, over the days: he moved from Rancagua south of Santiago to Concón on the coast. He works in mining. He loves his family. He doesn’t want to see David.

“Nathan, it’s like this,” says Pin slowly, over the phone. “David’s picture, maybe it saved this man’s life. But people here are tired. They don’t want to talk more about this. And he has had many problems because of that picture.”

We try more avenues. Pin talks to another of Daniel’s confidants. “He was tortured, Nathan, he was tortured even before David took his picture.” She says this almost pleadingly, as if imploring us to understand that it is not our right to simply intrude on the life this man has built. “It is not as simple as you two think.”

The day before we have to leave, we have breakfast with Maria Jose Martinez, who made the mini-documentary about Daniel. She brings with her a youngish photographer in a combat jacket named Mario Ruiz. Ruiz has brought his Macbook to show his work—David’s pictures have made him revered in certain circles, particularly among fellow photographers. Ruiz has made a small movie of his stills of Chile’s massive student protests—tear gas, riot police, field tourniquets—and set it all to a heavy metal soundtrack, which he plays at high volume in the breakfast room at the hotel.

Ruiz is the man we should have met on our first day. It turns out that he had family who lived near Daniel’s house, and for years would stop by on Sunday afternoons to visit him. He had just gotten off the phone with Daniel’s wife, he says, and she would have gladly arranged a meeting, if we had contacted her earlier. As it is, Daniel is in the far north, working at the mines, and can’t be reached there. It is no secret, also, that mining is a conservative industry in Chile. “He had many problems getting work after he was released,” says Mario. His fame—as a prisoner of the rightwing government—was tantamount to infamy among the miners. He has been running away from that photo for years.

Campaña calls shortly afterward. “You cannot trust them,” she says. “I have heard from a very important man in the area, a politician, that Daniel is still in Concón. He is simply hiding from the media. Nathan: you must decide if you want to go to Concón. It is the only way.”

I am too tired, and frustrated, to think through the layers of conspiracy. We stay in Santiago.

Instead, it is David’s turn to make a final plea, this time through Facebook, in a letter he has drafted to Daniel’s daughter. He reads it to Michael Magers and me on the balcony of Magers’ hotel room, to see what we think of it.

The letter starts by saying that he doesn’t need to make a new portrait of Daniel, that he would be happy just meeting him. He wants Daniela to know that he was worried about Daniel all these years, afraid of finding out what had happened to him.

He reads on: “It wasn’t my intention to make your father either famous or to create for him a trail of journalists which would come to be a problem after all these years. I simply wanted the rest of the world to know that in that one moment…”

David stops, suddenly choked with emotion. It takes two tries to restart reading the next sentence: “I simply wanted the rest of the world to know that in that one moment, a young man about my own age, anonymous to me as I was anonymous to him, was experiencing the kind of terror which spoke a great deal about the politics of Chile…”

The letter continues. It makes a fine case for wanting closure, to simply shake the hand of this man whose face he had lived with for forty years. It was beautiful and heartfelt, and he was on the brink of tears while reading much of it.

He sent it that afternoon, and never heard back.