On Saturday before Easter, dozens of papier-mache effigies will go up in flames in Mexico. This family has been making them for centuries.

Every year on Saturday before Easter, a line forms outside Felipe Linares’s three-story home in the Merced Balbuena neighborhood of Mexico City. The visitors enter a few at a time, wandering up rickety staircases into rooms packed to the rafters with giant papier maché effigies. Some of the effigies are up to three meters tall, made over the course of several days only to be destroyed in the neighborhood’s spectacular annual ritual of ephemeral art: la Quema de Judas—the Burning of Judas.

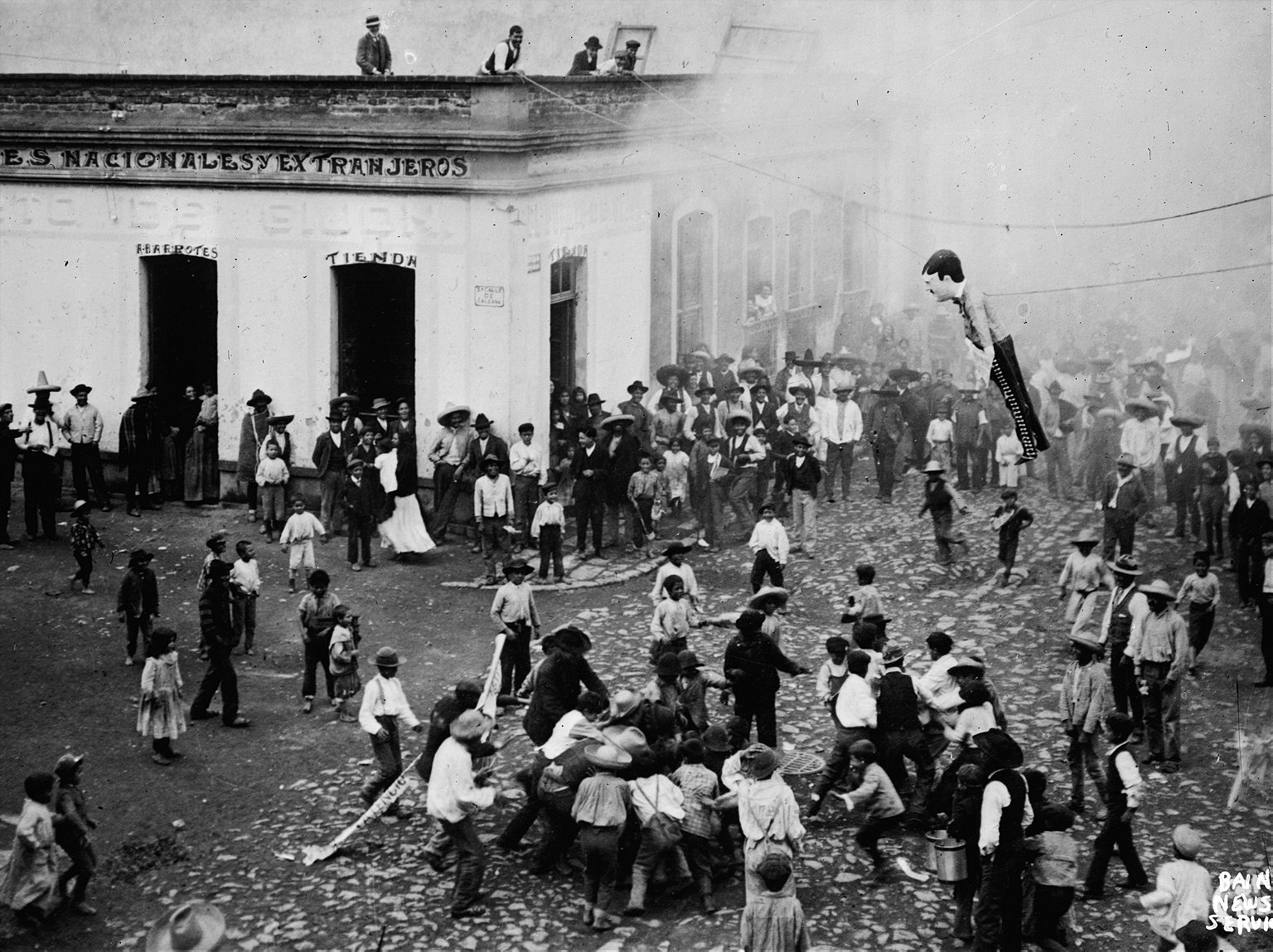

As soon as the sun sets, neighbors hoist the figurines, stocked with fireworks and wrapped in cartridges of gunpowder, on a wire strung across the street, which serves, for that night, as the community’s central plaza. An excited crowd gathers as they light the figures on fire, one after another: an elaborate fireworks display that is also a catharsis as the effigies spin, burst, and burn. Colorful demons, an ISIS fighter, and El Chapo; Donald Trump and his border wall, Pope Francis with a mountain of bills glued to his body, a “hipster” in glasses with a Starbucks cup in one hand and a cucumber in the other were all among the images offered up to public animus in recent years.

This is an election year, so the Linares family, and people from around the city (and, increasingly, the world) who come here to prepare their Judases, will be crafting at least a few images of Mexico’s presidential candidates.

Introduced by colonial evangelists and developed in provincial cities like Guanajuato and San Luis Potosí, the burning of Judas was originally a symbolic rewriting of biblical history, doling out popular justice to the New Testament’s greatest villain, Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus for a handful of change. Still celebrated in middle-class neighborhoods throughout central Mexico, the Quema today is practically the same event portrayed in Diego Rivera’s murals in the 1920s—save for the liters of beer served in chile-rimmed cups, and the more politically pointed message of the effigies being burnt. Fifty years ago, Felipe, now 83, told me, most of the pictures would have been the traditional devils. “The government had more control than they do now,” he said.

A working-class tradition, the Quema has never played a conspicuous part in the capital’s Holy Week Celebrations; effigies were never burnt in the Zócalo, the city’s grand ceremonial plaza (though they were burnt in the neighboring Plaza Domingo). For centuries, the tradition was dispersed widely, with Judases set ablaze at each of Mexico City’s thousands of pulquerías, the simple bars serving the agave-sap liquor that once dominated the region’s drinking culture. As the city government started to enact stricter laws on fireworks and gunpowder in the middle of the last century, those displays gradually disappeared, concentrating in districts like Merced Balbuena, an often overlooked colonia behind the famed witchcraft market, the Mercado Sonora. It’s a celebration for a city in resistance against the voracious neoliberal economy, a bacchanalian purge of a year’s worth of anger and injustice.

In early March, I met Felipe, the small, affable patriarch to a family of artisans in Merced Balbuena that has been dedicated to the humble craft of cartonería, or cardboard-work, since they first came to the city three centuries ago. In those days, he told me, the streets were still cobbled, and his parents would send for milk from the stable down the street where today there’s a fire station. When the city government decided to pave and straighten the road, Felipe’s son Leonardo, 54, added, they found pieces of clay and wooden molds that his ancestors had used and buried. “They thought it was an archaeological site.”

I asked Felipe how it feels to watch days of their work burn in just a few seconds. “The satisfaction for us is that they burn well,” he said. “That’s what they’re for.”

Making Judases occupies just a small part of the year for the Linareses, who have worked as cartoneros for generations, practicing a craft tradition introduced (along with paper) during colonization. In Holy Week, they spend days making their effigies. For Día de los Muertos they make decorative skulls and skeletons. For the rest of the year, they make piñatas, masks, and, most famously, alebrijes, the brightly colored, fantastical animals popularized outside Mexico in last year’s Oscar-winning Pixar film, Coco (though they’re called alebrijes in the movie, the Linares family says that’s a misnomer). “We’re better known for alebrijes than for making Judases,” Felipe said. They should be: the Linares family invented them.

The first alebrijes, Felipe told me, were conceived by his father, Pedro Linares López, in 1936, in the same house in Merced Balbuena where the family still lives and works. “My father had a gastric ulcer for something like four years, and at one point it burst—it’s a piercing pain that I wouldn’t wish on anyone—and while he was stuck in bed, the idea came to him. He was the creator of the alebrijes,” Felipe said, with no qualms and no hesitation, “both of the figures and the name.”

An authentic alebrije, according to Leonardo—short and loquacious in a paint-splattered smock—should be made from papier mache or cardboard, paste and paint; it should have bulging eyes, a long tongue, scales, wings, and claws, and either curled horns or crests like a rooster’s. The Linareses sign their alebrijes by hand and, and pack them off for shipments abroad in big protective boxes, like any other artwork. There was a time when the family worked closely with the Mexican government, which was in the habit of presenting Linares-family alebrijes to diplomats and distinguished visitors. “We’re not pricey if you consider that making a mid-size alebrije”—these would typically sell for about 15,000 pesos, about $814—“sets us back by 20 or 30 days.”

Though the family registered its invention with the National Copyright Institute and the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property in 1994, their contribution to national craft is barely recognized within Mexico. Each autumn the Museo de Arte Popular (Folk Art Museum) organizes a parade of giant alebrijes that processes from the Zócalo down the Paseo de la Reforma, a historical, tree-lined avenue that runs through the heart of the capital. If you asked any among the thousands of people who gather for the parade where alebrijes came from, they would likely answer Oaxaca. It’s an understandable mistake. Since the 1980s, wooden alebrijes decorated in vibrant patterns of vinyl paint have been the economic mainstay for the villages of San Antonio Arrazola and San Martín Tilcajete, both located in the southern state famously associated with indigenous culture and craft. These are the figurines that tend to light up the shelves of Mexican art enthusiasts around the world.

“Their origin comes from the dream of an artisan, who, while in a forest, heard a group of people speak the word alebrijes,” a placard in gallery four of the museum reads. In the museum’s gift shop, wooden alebrijes range in price from 100 to 89,000 pesos (about $5.50 to over $4,800). The most expensive is a white fox, roughly the size of an adult’s arm, carved from the fragrant wood of the copal tree.

The Linares family has never filed suit to demand recognition. “We can work, or we can sue.”

According to Felipe, the first Oaxacan alebrijes, which represent recognizable animals adorned with wings or horns, cannot be called alebrijes. On a recent visit to San Antonio Arrazola, Leonardo gave a workshop in which he explained the difference between his family’s craft and the wooden animals made there, which, he says, should be called tonas. “If the people who made Coco had done their research right, they would have come here,” Alauda Acuña, a history student who comes to the workshop each year to build her own Judas, said.

The first tonas were made in San Antonio Arrazola after Manuel Jiménez Ramírez, an artisan from that village, was featured in an American documentary on Mexican craft alongside Pedro Linares. Even still, when the family sought a copyright for alebrijes, Felipe told me, it was more to protect against copies from China than workshops in Oaxaca. Even as the Oaxacan origin story has come dominated the narrative of their family livelihood, the Linares family has never filed suit to demand recognition. “We can work, or we can sue,” Leonardo said.

I asked Leonardo whether the family considered themselves artisans or artists. “We’re both,” he said, “they call us artists abroad and artisans in Mexico. We’ve been in France to give workshops and demonstrations, and we have clients in the U.S., England, France—as far away as Scotland.”

But even as alebrijes have become more popular both in Mexico and abroad, the Quema de Judas, a tradition that predates them by centuries, has begun to fade, going the same way as other Holy Week traditions, like bathing in public fountains. When Felipe was a boy, the family would craft its Judases mostly to sell to the pulquerías and other families who would burn them out front. In an essay published in the 1963 book Todo empezó el Domingo (Everything Started that Sunday), journalist Elena Poniatowska wrote of the prohibitions on fireworks imposed under the then mayor of Mexico City following a horrific explosion that took place on the highway to Puebla. After that, Leonardo said, “the tradition started to concentrate around here.” The journalist Édgar Anaya, in his 2010 book Ciudad de México desconocida (Unknown Mexico City), wrote: “More than help, the authorities have tried to end the burning.” But Felipe said the government has never given them trouble in Merced Balbuena. “Fortunately, there’s never been an accident,” he said.

Felipe is full of stories from the city’s past: of Diego Rivera’s visits with his father, who received the National Medal for Sciences and Arts in 1990; of the family’s ancestral origins in Xochimilco, where they worked as cobblers hundreds of years ago. Merced Balbuena, a neighborhood many visitors hardly realize exists, is home to the church of Ixnahualtongo, which, according to some scholars, might stand on the very place where the Aztecs first founded the city of Tenochtitlan. At the edge of what was once the island city, Merced Balbuena would have been one of the entry points to once the world’s most populous city.

A few days before the Quema when I returned to the workshop, the whole family was hard at work, building the frames of their Judases out of reeds and masking tape and draping them with papier mache made from stacks of periodicals. I asked Leonardo what he’ll do if print media dies. “I guess I’ll go out of business,” he said.

Drying on the roof were completed effigies of an obese cowboy smoking a cigar, a lithe norteña in a cowboy hat, and an oversized skeleton in a trench coat stamped with the symbol of Mexico’s major political parties and foreign oil companies, a commentary on the recent privatization of the energy industry.

Downstairs, surrounded by half-finished alebrijes and decades-old papier-mache dolls, Acuña worked with Leonardo to prepare one of the two effigies she’ll make this year: “a three-for-one” Judas, with the heads of all three major presidential candidates on one big body. “It takes all three to make a proper politician,” she quipped. “For me, it’s a powerful form of protest.”

[Header image by: Michael Snyder]