Life and death in La Rinconada—one of the world’s most desolate places.

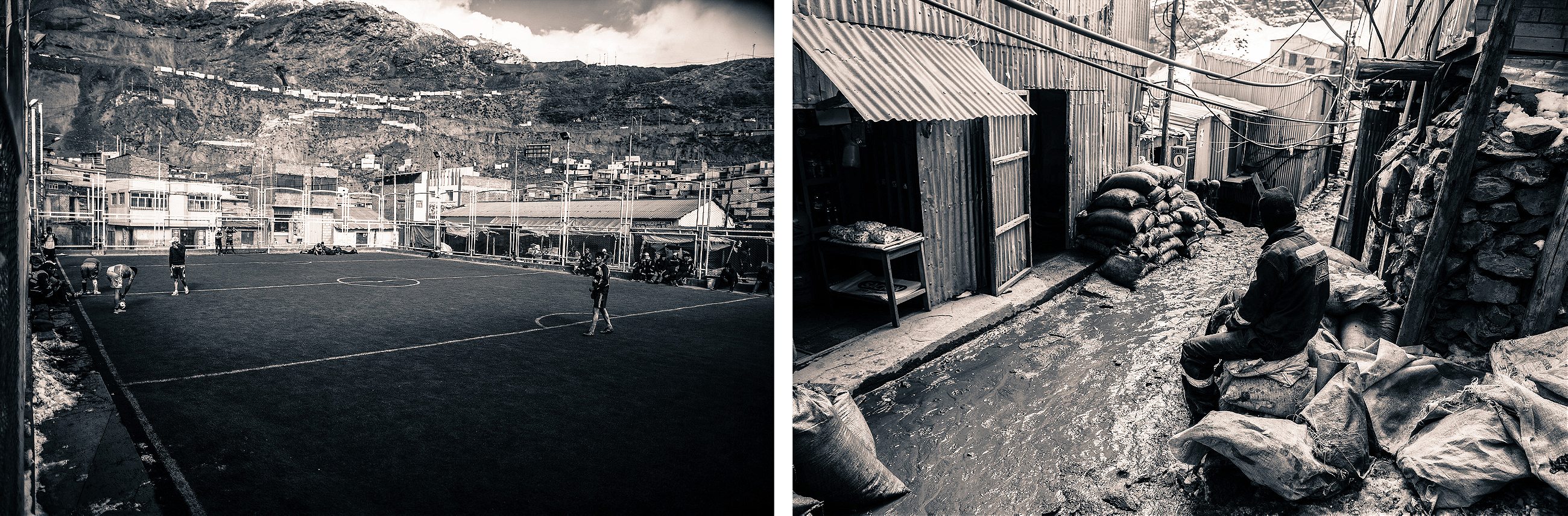

La Rinconada’s population fluctuates with the price of gold. Since the early 2000s, countless people have gravitated to its mountain from small towns all over Peru, seeking their fortunes in a place where there are no guarantees. Located in the southern Peruvian Andes, the isolated town sits below a daunting peak known as la Bella Durmiente, “Sleeping Beauty.” More than 100 tons of gold are extracted from it annually. At an elevation of 17,000 feet above sea level, La Riconada is the highest habitation of any community on earth.

The environment is harsh. Those who come here face various forms of altitude sickness, like exhaustion, striking headaches, dizziness, nausea, and insomnia. Elevation also causes blood problems for long-term residents. It is said that the mines of La Rinconada kill workers quickly, through accidents and cave-ins, as well as slowly, by developing terminal health problems from the poor living conditions.

Photographer Sebastian Castañeda recently visited La Rinconada—a place known to be unwelcoming to journalists and outsiders. Though he says his presence with a camera was not well received, Castañeda was able to observe the community by accompanying a local miner to work during the daytime. “The situation is very different during the nights,” he says. “There are often assaults and murders. The night before my arrival, a miner was shot and killed.”

La Rinconada is not an official community, nor is it recognized by the state. Access to electricity was established in 2002, but there is still no sewage or clean water infrastructure. There are independently-owned hotels, a school, restaurants and nightclubs, but no banks or hospitals. The cold climate regulates the deficient sanitation, so when temperatures rise above freezing level, the town turns into a muddy cesspool of bacteria and thawing waste. Mercury and cyanide are the primary ingredients used to process gold, and most of the ground area and water sources in the town are highly contaminated.

Castañeda, like other journalists who have visited the mines, was dismayed to hear of the curious deaths that occur underground, both from accidents and at the hands of fellow miners. Some NGO reports have cited an average of a half-dozen homicides per month—most commonly stabbings. The Quechua people consider miner deaths payments to Pachamama, the mother of the earth. There are also stories from La Rinconada about missing children and blood sacrifices being performed to honor the mountain gods.

La Rinconada miners work on a traditional labor system called cachorreo, where they work 30 days—unpaid—for the company that claims rights to the mines, followed by one or two days (depending who you ask) mining gold for themselves as a form of payment. What can potentially be earned in the non-company days determines the payoff from a month of labor. It’s not uncommon for miners to walk away with nothing. But even with such high stakes for reward, a recent effort to reform the cachorreo system into a national Peruvian salary model was heavily opposed by the miners. The cachorreo offers a greater chance to earn money, not to mention the opportunity to smuggle gold from the mine during the days spent working for the company.

At all hours of day and night, groups of female miners, called pallaqueras, work outside the mine entrances. They bang on rocks with small hammers and sort through tailings in search of gold. Many pallaqueras are widows or single mothers, who come from all over Peru. Women are not permitted to enter the mines, so they spend tireless hours outside at the top of the mountain, trying to earn a living. The entrances to the mineshafts are a 30-minute hike from the town. The pallaqueras devote a portion of their meager incomes to purchase gift offerings to the mountain deities in return for good fortune.

“La Rinconada is a lonely place to work,” says Castañeda. “People work long hours to earn an income and support their families, where others work to earn money for alcohol, drugs, and prostitutes.” Black market gold is said to be Peru’s leading illegal export, and the value of gold in La Rinconada reflects the daily market rates set in New York and London. From the mine, the gold makes its way into small processing shops before it’s moved down the mountain to Juliaca. From there, it’s trafficked over the border to Bolivia and joins the global distribution network of gold trade.

Year after year, less gold is pulled from the depths of Sleeping Beauty. Yet as the community becomes more polluted with toxins and swells far beyond capacity, new people continue to arrive in search of fortune. Whether they find it or not, one thing is certain: La Rinconada ultimately has no future. —Eric Greene