An Israeli photographer documents Azerbaijan through the small artifacts and experiences of daily life.

As Armenians commemorated the genocide centennial across the world last week, little attention was being paid to the alarming escalation of a smaller yet seemingly endless ethnic conflict Armenia has with a neighboring country: Azerbaijan. Yet experts say that the region is closer to open war than at any time since the 1990s. At the center of the conflict is Nagorno-Karabakh, a de facto autonomous region locked inside Azerbaijan that Armenians took over more than 20 years ago. A May 3rd parliamentary election there–considered illegal by Azerbaijan and most of the world–could increase tensions in the oil-rich region south of of Russia. But war was not the only story that Israeli photographer Tomer Ifrah wanted to tell when he started photographing Azerbaijan. Like much of the world, he initially knew very little about the small country of 9.4 million that is sandwiched between Russia and Iran and flanked by the Caspian Sea. But after six weeks of traveling and documenting daily life across the country, he’s convinced that the world should be paying more attention to Azerbaijan and its unique culture. He joined R&K from Rio de Janeiro.

Roads & Kingdoms: What are you doing in Brazil?

Tomer Ifrah: I am working on a project here about cityscapes. It’s a great city, a fun place to be. But I’m not staying here much longer, I will be in Azerbaijan again very soon for a new project.

R&K: What is it about Azerbaijan that makes you want to go back?

Ifrah: I didn’t know much about the country the first time I went. I was contacted by a Russian reporter for a project there in 2013. I had very little time to prepare, so I did basic research and then I just went. It was a big surprise. I discovered things little by little just by being there. I looked at this project as a photographic diary. From a village in the mountains to a refugee camp to the capital, Baku, each place had its own issues and its own aesthetic, so I decided to document the simple things of daily life. The reporter came for a week and joined me to visit the refugee camps and Khinalig, the village in the mountains, but I extended my trip and stayed for about six weeks.

R&K: What were your first impressions of Azerbaijan?

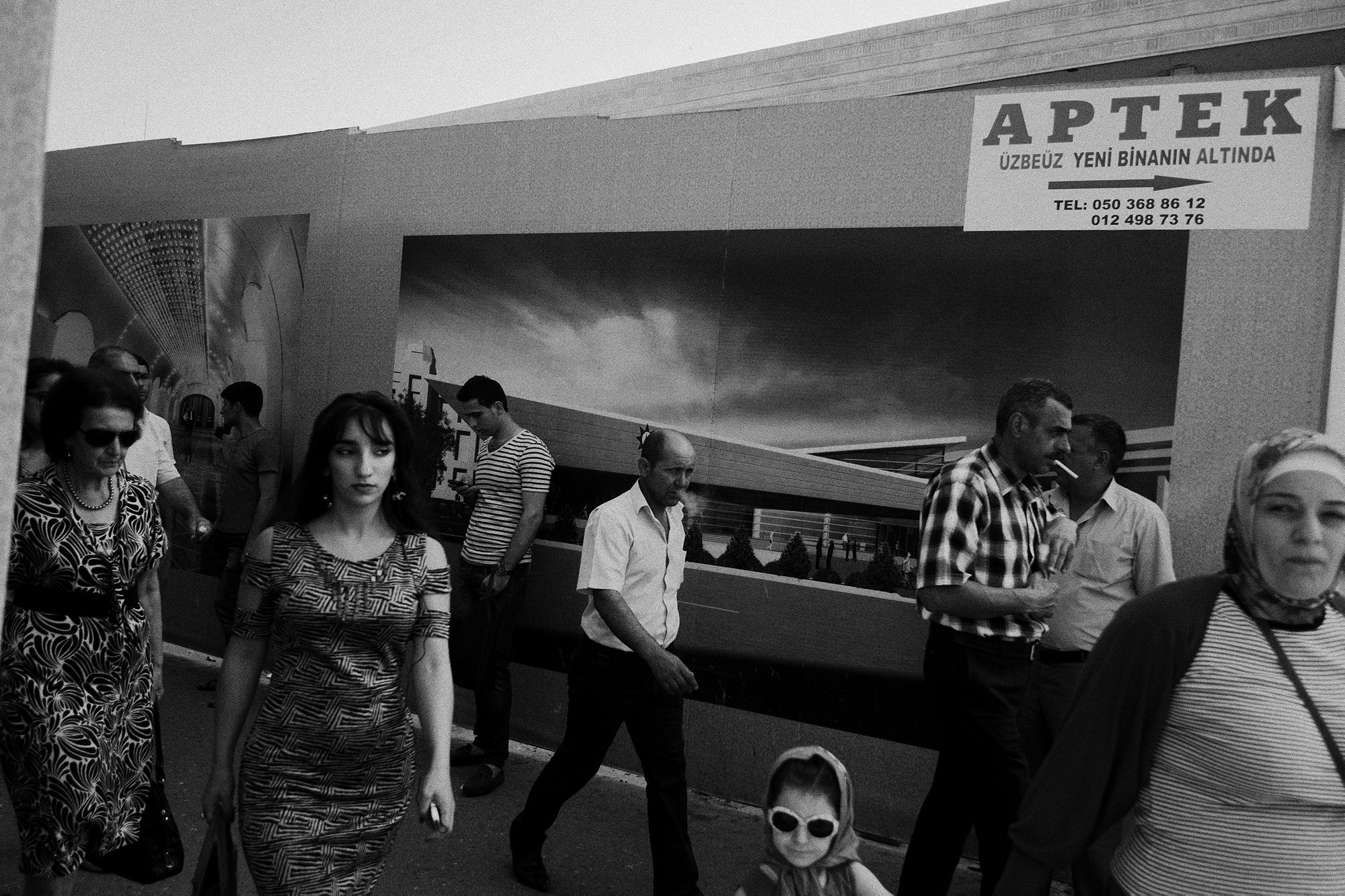

Ifrah: I landed in Baku and went straight to my hotel, where I went on the roof and got a view of the entire city. My first impressions were of the capital and all the skyscrapers and buildings, the new developments. It was very clear that the city was going through massive changes, which was interesting to see. I knew a little bit about Baku already so the surprises came later, when we left the capital and visited the villages and smaller cities. There, I discovered this very unique Azeri culture. It’s a mixture of influences but still there is something very unique to the people there, which is present in things like food and gestures for example. That’s what I tried to capture by photographing the small things.

R&K: Where exactly did you go?

Ifrah: We planned the trip in order to get a variety of settings and issues. This village that we went to for example is ancient and it’s very difficult to get there, so people only depend on themselves for their livelihood. In the winter, they are totally isolated because the roads are blocked. They’ve managed to keep their traditions alive, which was very special. The way we traveled is we drove north from Baku and we stopped in interesting places along the way. The places were all different from one another but the thing that combined them all was the uniqueness of the Azeri culture.

THEY SAY THAT PEOPLE ARE DYING ON A DAILY BASIS IN NAGORNO-KARABAKH

R&K: Was it different though when you went to the war zones?

Ifrah: No, but we heard very difficult stories in Nagorno-Karabakh. It’s a long and painful conflict that has been very destructive on both sides. They say that people are dying on a daily basis in that region and you hardly hear about it. Once in a while it gets in the news, but not as much as it should. It’s also a very dangerous area to work in.

R&K: When you were in the capital, did you feel like you were in a country at war?

Ifrah: No. That’s the thing with Baku. It’s a totally different reality in many ways. It’s a city of business, you have a middle class and an upper class, you can find big brand shops. Azerbaijan is small, but it’s very rich in natural resources, so in recent years investors from all over the world have been going there. It’s prospering at a great speed.

R&K: Azerbaijan occupies a very interesting and strategic place on the map. Did you feel an intersection of many different cultures?

Ifrah: One of the first things that I noticed there was that the language sounded to me like a mixture of Turkish, Russian and Farsi. It’s a very unique-sounding language. And that was a metaphor for everything else I found there. The main influences I recognized were from Turkey and Iran, and from the country’s Soviet past. In fact, many Azeris speak Russian.

I WOULD GO TO THE PLACES THAT PEOPLE PASS THROUGH DURING THE DAY

R&K: How did you approach people for this project?

Ifrah: In each place that I went to, I would study daily life. I would just walk around Baku for example, and like a stream of consciousness, I would go to the places that people pass through during the day. I explored the public realm first. And from there, I went deeper, inside restaurants or people’s homes. It was going from the public to the personal. When we went to the village of Khinalig, a family invited us to stay with them during a wedding. I lived with them for a few days, I ate with them and saw how they lived. The ceremony lasted three days. It was a very simple and very beautiful thing to be a part of.

R&K: By documenting these experiences, what do you want to communicate about Azerbaijan?

Ifrah: I hope I can show a little bit of this culture and that people will get curious about Azerbaijan. I remember before going, I was in India and not many of my friends there knew where Azerbaijan was. So this project was to share the curiosity I had about this place. There is a kind of enigma there. I enjoyed discovering a country that was completely new to me, and I hope to work on a new project there that furthers my understanding of it.