Rural Kenyans are falling victim to a war over their most precious resource: livestock.

Cornelius said the drive to Arabal would take an hour, but it’s been more like three. Already a full day’s journey from Nairobi, we chanced that by dark we could reach the Arabal river and make it back to the town of Marigat to sleep. But now the sun is inching westward and our car is running out of gas.

This isn’t a place you want to be stranded for the night. Baringo County is in the midst of a war over livestock. A severe drought has forced Pokot herders to drive their cows and goats from the dry flatlands up into the beautiful mountains above Lake Baringo in search of grass. But this land is inhabited by Tugen, and the Tugen are struggling to feed their own livestock as it is.

In central Kenya, grass and vegetation can be a matter of life and death, and not just for the animals. Pastoralists depend upon milk and meat for their livelihoods. Deprived of that income, entire communities can become food insecure. For many families, livestock are their only assets: they have no bank accounts, no land to farm.

Combine those stakes with the fact that experts believe there are 530,000 to 680,000 guns in circulation among civilians in Kenya. Guns have long been traded across Kenya’s porous border with Somalia, but some have recently been traced to Uganda and South Sudan. Most herders who carry them do so for self-defense—to protect their animals from raiders. But others use them to raid.

Some of the Pokot who have crossed into the administrative region of Arabal this year fall into the latter category. Since the drought began late last year, there have been dozens of shootouts between Tugen, Pokot, and the police. Thousands of heads of livestock have been stolen, though just how many thousands is anyone’s guess.

The violence climaxed in February; I am here to learn about the murder of two politicians, and the bloodshed that followed their deaths. I’m traveling with Cornelius, a university student from the Tugen tribe who asked that I only use his first name, and two fellow journalists. The dirt road we’re traveling has itself been the scene of several shootings. Police patrol it in armored personnel carriers that resemble small tanks. Authorities appear overwhelmed by the armed bandits, who often know the territory better.

“They come first and surround the police post so no police will come out. And then they attack the area all around,” says Cornelius.

Survivors of these shootouts speak of the Pokot as if they were immune to bullets, as if they were sharpshooters who never missed, as if their ammunition were infinite. But survivors are hard to find.

We’re on our way to visit a woman who was shot by Pokot gunmen just a few weeks earlier. She lived, but the old man she was with, whose cows and goats had been stolen just four days earlier, wasn’t so lucky. His murder left an entire family grieving and without an income—victims of a war over grass fought with guns. It is an ongoing problem—authorities told IRIN News that 580 people were killed in cattle raids in Kenya between 2012 and 2014—but seems particularly intractable in Baringo County.

Some say the violence comes down to simple mathematics

In Arabal, a small, mountainous district where some families practice small-scale farming but most rely on livestock for their livelihoods, some blame the recent wave of cattle rustling and shootings on the desperation brought on by the drought. Others say the violence comes down to simple mathematics: today, there are more people, more animals, and more guns, but only as much land there’s ever been—and even less grass.

But some believe the violence and murders that took place in Arabal this February was simply revenge—revenge for the midnight assassination of two Pokot politicians.

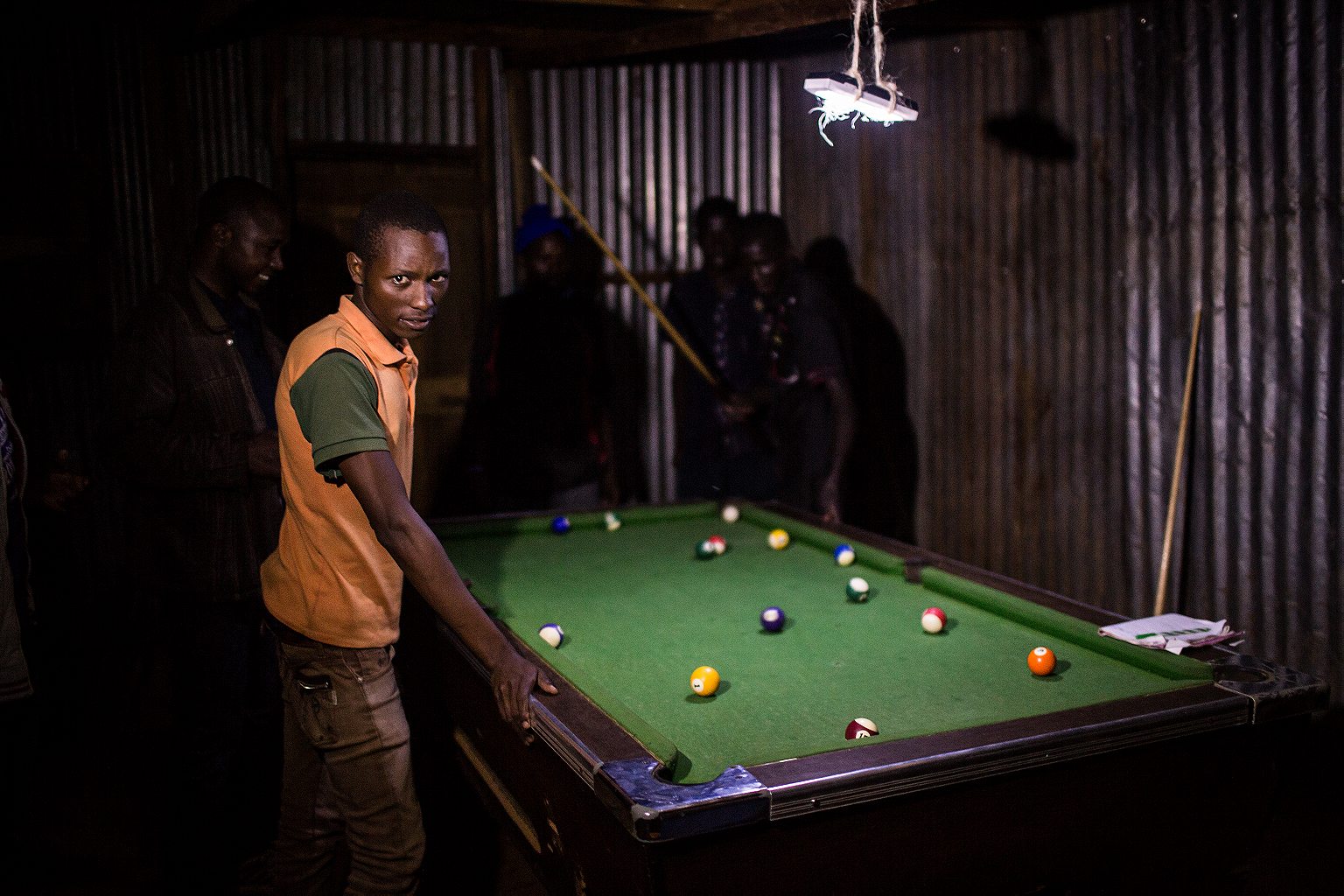

On the southern road to the town of Marigat there is a gas station that, at night, looks like a beacon, its white and red lights so bright that they hurt your eyes. Behind that gas station is the T-Junction Bar, a collection of open-air cabanas set apart from one another on a hill, each outfitted with wooden tables and chairs; a sort of private, no-frills lounge.

Unlike the gas station, the bar is dark. Music blares across the lawn. Marigat is a small town, and its few residents of wealth—the politicians, the business owners, mostly men—would come here at night to socialize. One of the bar’s most loyal customers was a sitting Member of the County Assembly (MCA) of Baringo, a man named Frederick Kibet Cheretei who hailed from the Pokot tribe.

Kibet would hole up at the bar the way a college professor holds office hours. “This is the only place you would find him,” says the bar manager, who asked that his name not be used. “The MCA spent three days here of the week before he died. Morning and evening.”

The other man, an engineer named Symon Pepe Kitambaa, was a candidate running for Parliament. He came less frequently, but often enough that the bar manager still knew his order by heart: chicken, with warm bottles of White Cap beer.

Late the night of Friday, Feb. 17, the manager was inside his small office near the entrance. “I heard the gunshots, and tried to see where they were coming from,” he says. Then he saw them: two masked gunmen, running up the lawn directly toward the politicians; they clearly had a target in mind. “You could see the sparks in the sky,” the manager says of the muzzle flashes from the guns as they fired.

The manager ran out of his office and jumped over a fence to escape. He spent more than an hour crouching on the dark hillside opposite the road. When the gunmen finally left, he returned to the bar to witness the carnage: the two politicians’ bodies lay near the entrance. They’d been carried there by staff and patrons from the cabana where they were shot. The floor was covered in blood. One man had been shot in the head, while the other was hit in the stomach, his organs spilling out.

A waitress told the manager that the gunmen and their associates—five to eight in total—had proceeded to set the men’s vehicles on fire. Noticing that Pepe was still alive, the waitress lifted him and began carrying him down the hill toward the exit, but the gunmen fired into the air—a warning to stay back, to leave Pepe to die.

I used to see AKs in my village, but nowadays it is the G3 rifles

In the days that followed, some theorized that rival Pokot ordered the assassinations. Three weeks after the murder, police arrested five suspects, including the bodyguard of a rival politician. But if the question of who murdered the men and why remains cloudy, what happened next is clear: Marigat is Tugen territory, and having seen Pokot leaders murdered there, some of the Pokot decided to retaliate.

“I used to see AKs in my village, but nowadays it is the G3,” says the manager, of the type of weapon originally developed by a German manufacturer in the 1950s for use by NATO forces. These powerful rifles have proliferated across the region in recent years, and their increased killing power was now brought to bear.

“The killing of the two politicians led to tension between members of the Pokot community and the Tugen,” read an article in the Standard newspaper three weeks after the attack. “In the two weeks of mayhem, nine people were killed and hundreds of others fled their homes.”

Arabal was up in arms.

Cornelius isn’t the type to volunteer directions. At every fork in the long, winding road to Arabal, we slow down or stop entirely as he makes up his mind as to which way to go. The land around us is dry and empty. He says the only crops people bother planting here are maize and watermelon, but we don’t encounter much of either. Mostly it’s just thorny acacia trees and other unsavory looking shrubs.

On the rare occasion we pass any people, their colorful clothes offer relief from the sun-bleached surroundings. Once, after losing our way, we flag down two older women, who approach our car and greet us. Their heads are wrapped in scarves, and one has large holes in her earlobes. “They are Kalenjin,” says Cornelius as we backtrack to the road.

The Tugen and the Pokot, he explains, are actually members of the same ethnic group, the Kalenjin. There are seven tribes, all of whom speak similar languages. But some Tugen find the Pokot language difficult. “We don’t even understand each other,” says Cornelius.

I ask Cornelius why members of the same tribe would steal one another’s cattle. “Outdated culture is the driving force,” he tells me. “These people from Pokot believe that raiding cattle is their culture.”

But Cornelius is also at pains to explain that the Pokot in Baringo County have it rough. Their land is less arable, and Kenya’s leaders have paid them far less attention than the Tugen.

“The former president came from here,” he says, referring to Daniel arap Moi, who led Kenya from 1978 until 2002. “Moi was Tugen. Moi was in power 24 years.” In Kenya, a quarter century at the wheel means a quarter century of investment and development for your people—in Moi’s case, the Tugen. The year he left office, Moi inaugurated Kabarak University, which we passed on the drive up to Baringo. No Pokot has ever managed to build a university, much less serve as president.

The fact that Cornelius, who hails from a tiny collection of huts in rural Arabal, managed to get admitted to a major university where he’s studying industrial chemistry, is testament to that disparity.

He says it’s rare to come across Pokot classmates, though when he does, the rivalry of the outback doesn’t breach the classroom. “I know some of them. We are friends,” he says. However, he still believes the Pokot view raiding as part of their heritage. “There are some Pokot who are students, and on the off-season, they go raiding! It’s hard for Pokot to change, really. Even those who come to learn, they still raid. It’s a cultural thing.”

The generalization that Pokot have an inalterable rustlers’ mentality may well be a Tugen bias, but Cornelius allows that it could be “politics” driving the bloodshed. When I ask what he means, Cornelius points to a stretch of road ahead of us. He says a Pokot army general was killed there back in December 2014. It was said that he bought a plot of land in Tugen territory. The way the story goes, Tugen men with guns shot him, then lit his SUV on fire.

But the violence didn’t end there. “The Pokot retaliated,” says Cornelius. “[The Tugen] were forced to move within two days… Definitely they would want revenge after we had killed their person.”

Perhaps what unfolded after the assassination of Pepe and Kibet was no different. Perhaps seeing their elected leaders slaughtered in public sent a signal to the Pokot that nobody could protect them—that they had to set about protecting themselves.

Our car barely makes it up a steep bend in the road, and at last we arrive at a narrow plateau known locally as ‘Dam’ for the manmade dam that collects water here during the rainy season.

The people in Dam stop what they are doing to stare at us. Some sit on thin wooden benches in front of shacks that sell biscuits and other snacks. Bags of charcoal are scattered about. Others lean against huts made of tin—temporary homes. A bullet cartridge lies on the ground just a few feet from the road. Markings reveal it was manufactured at Kenya’s government ammunition factory. What became of the person or thing that it was fired at it isn’t clear.

Today, Dam is something like an internally displaced persons camp. After the two politicians were killed, violence forced dozens of people to flee their homesteads in the woods and squeeze in here with family members. A few of them approach our vehicle to ask what we’re up to. When we say that we’re journalists here to investigate cattle rustling, one man tells us that in February, just days after the politicians’ murder, he lost 117 cattle to Pokot rustlers. He was left only with the calves. Cornelius knows the man and remembers the incident.

“It was rumored that the people who killed these Pokot [politicians] were from this area,” Cornelius says. “So the Pokot now say it was us who killed these people at Marigat.”

After setting out to survey the area, we come across the Arabal river, which turns out to be just a shallow, rocky creek. Cornelius describes the river as a natural boundary—the side we’re on is generally safe, free from intruding herders. But just across it, on the northeastern side, gun battles periodically erupt between armed bandits and police. Cornelius quietly mentions that there’s a school just a short drive across the river that’s been shuttered due to the violence, abandoned by teachers and children alike. He says it isn’t far. We decide to go find it.

Expecting to find the school empty, we’re surprised to discover half a dozen men hanging around outside, some shirtless, some sipping chai. They’re police officers, and they’ve commandeered the school as a makeshift operating base—or at least, a place to wait for a fight to erupt. Their tall, soft-spoken commander, Isaac Okech, describes the cattle rustlers’ modus operandi.

“First they do reconnaissance—survey the area. Then they go assemble themselves and come back with guns,” he says.

When I ask how his officers fare when they engage the rustlers, he says it isn’t good.

“They understand this place better than I do. They can steal the cattle from afar, [and] by the time we find them they have moved along to their hideouts.”

Okech walks us over to the shade of a tree to introduce us to the only teacher who remained behind to look after the school complex during its closure. Bethsheba Chemoiwo, 26, began teaching here four years ago, but she says the school has been shuttered for much of that time.

In January 2015, the school’s security guard was killed here—shot dead right on the school grounds. After that, parents stopped sending their children to school. In January 2016, the teachers persuaded them to let their kids return, and the school reopened. But this February, just days after the murder of the two politicians in Marigat, a teacher from a nearby school was shot and left for dead in the woods not far from here. The school has been closed ever since.

Back in Dam, one man says that immediately after the assassination, “there were frequent attacks. The father of this man was killed.”

The man toward whom he gestures is 23-year-old Vincent Kurui. One afternoon in February, “My father was herding our livestock. It was late afternoon, around five, when the Pokot raiders came and shot,” Kurui says. “No bullets hit him. But he had to flee, and those guys took his livestock away.”

Forty-three cows, 120 goats. “They took everything,” recalls Kurui. Their livelihood stripped from him, his father resorted to cutting down trees to turn into charcoal. That’s what he was doing the afternoon of Sunday, Feb. 19, the day after the two politicians were killed.

Kurui offers to show us to the location. He jumps in our car and we set off slowly, cautiously, down the same road his father had walked. Along the way, Kurui begins to reminisce. He tells us that his father was everything to him. “The person I have become today is because of my father.”

As we drive up a steep hill, Kurui tells us to stop. We pull over and he walks swiftly down to a dip in the road. It’s a ditch where water would pass, if it ever rained. Standing on a rock, Kurui points eastward up the hill. That’s where the armed rustlers appeared. His father and aunt, who were walking together, were chased and ran to opposite sides of the road.

“When he fell down he was lying on his back looking up at the Pokot warrior, asking for forgiveness from these guys,” Kurui says of his father. If the gunmen understood what he was saying, they didn’t show it. “They shot him anyway—seven bullets to the chest, one to the head, and one through the mouth.”

That last wound must have been the first. “There were no injuries to the teeth. So they made him open his mouth so they could shoot him. He was found with the blood oozing out of the mouth.”

Kurui’s aunt, shot through the elbow and breast, bled on the side of the road for hours until an ambulance finally arrived to ferry her to a far away hospital. Later, she would recount the full story of what happened, but at the time all Kurui received was a message from two men who had come across his father’s body, telling him the news. One told him not to come to the scene.

His father had been the breadwinner of the family. Suddenly, Kurui had six younger siblings to care for. After his family’s livestock were stolen—four days before his father’s death— Kurui had opened a small butchery in Dam. About once a week he buys a goat for 3,000 shillings—about $30 USD—then waits and hopes people will come buy the meat. If he’s lucky, he’ll profit the equivalent of a dollar or two. That’s about all the income he and his family have left.

When I ask Kurui why he thinks the cattle rustlers murdered his father, he pauses a moment to ponder the question.

“My father… it was just an accident,” he says. “They are just warriors. They were bound to kill anybody they came across in the road.” That is to say, Kurui believes his father was the victim of circumstance—that his murderers shot him simply because they saw him. So many people have guns these days, better to kill than risk being killed.

Weeks later, Kurui still feels sick when he passes the spot where it happened.

“I get scared,” he says. “My blood is scared away from my body every time I pass here.”

A storm is fast approaching, so we rush off to Kurui’s mud-walled, thatch-roof hut. It’s dark inside, and a small charcoal fire that’s heating a pot of water fills the room with smoke.

“We never used to have problems—we did not have wars like this,” Kurui’s grandmother tells me, as raindrops begin pelting the ground and children rush inside the hut for cover. When the rain stops, we begin the short walk to the gravesite. It’s covered with piles of thorn bushes, to keep animals from digging up the body.

The tombstone lists the man’s name and the date of his death: Paul Chelagat, Feb. 19, 2017. The day after the Marigat murders.

The next morning in Dam, we find Kurui’s aunt, the survivor, sitting on the ground holding her infant son. Nancy Cheptoo, 29, recounts to us the attack that left her brother-in-law dead.

“The first shot, which hit my hand, was from far away. I felt the pain. Burning. I screamed,” she recalls. She shows me the wound, which is badly scarred. She says that 10 men surrounded her and demanded her phone.

“And then they left.”

She doesn’t know why the men spared her life, but not Kurui’s father’s. “I feel that God has rescued me,” is the only answer she can come up with. Cheptoo unbuttons her shirt to show where the other bullet struck her—through her right elbow and into her breast.

What can be done to stop this violence? I ask.

“The government should go attack them and get revenge—kill them.”

Where, then, are the police?

“This is south Baringo,” says Cornelius with a smile. “We have all types of police.” He lists them off by their acronyms: AP (Administration Police), ASTU (Anti-Stock Theft Unit), GSU (General Service Unit). The local AP headquarters was just along the dirt road in Dam, so we walk right in.

The police chief in charge of the area, Corporal Maru, is sitting on a wooden bench outside a standard-issue police hut made of tin. He says he’s been stationed here in Arabal for three years now, and in Baringo Country for more than a decade. He tells me he has 10 officers under his command, but that they find themselves outnumbered by the cattle raiders. When I ask if the raiders have guns, he laughs. “Yes, they have guns! They are well equipped.”

Another officer, Daniel Mwanzia, tells me that these days, two weeks don’t pass without a shootout. He says the armed rustlers are getting savvier.

“They are learning,” says Mwanzia. “They see everything. They could be somewhere there [now],” he says, gesturing toward the mountains to the northeast, the area Cornelius described as no man’s land.

While I spoke with the cops, my two colleagues chased down some local herders they saw carrying rifles.

“It’s easy to get the guns,” one of the men told them. “Getting ammunition is easy,” too. But he wouldn’t say where he gets his. They walked right past the police station with their illegal guns and bullets, but the police didn’t stop them.

As the sun sets in Dam, we duck into a dark, one-room restaurant and order some grilled goat meat, the only thing on offer. A tall man wearing a camouflage jacket lingers at the door, so we invite him in. Turns out he’s a member of the KPR, the Kenya Police Reserve.

This reservist tells us that when he was recruited, he was given a gun and just a single day’s training

The KPR aren’t really police—just guys who are given guns and told to do the work that the police have been unable to do on their own, or prefer not to. Late last year, Kenya’s government began recruiting hundreds more of them. “We are not just giving uniforms to anyone. They are vetted, trained and given uniforms and they are answerable to officers in charge of police stations where they serve,” Rift Valley Regional Coordinator Wanyama Musiambo told a Kenyan newspaper last year.

But this reservist tells us that when he was recruited two years ago, he was given a gun—a G3—and just a single day’s training. Between mouthfuls of chewy goat meat, he says that just two months ago, raiders stole cattle right here in Dam. He and some other reservists gave chase, along with a few police officers. “They went far with the livestock, and we took another route. We went for like 20 kilometers or even 40, so that we could circle back on them.”

They laid their ambush, but they were no match for the gunmen who arrived. “These guys just keep to the bushes, while the police keep to the road. The police fear to get into the bush,” he says. “We ran because they were too many in number and the police were not helping. They are afraid of getting out of their vehicles.”

The next morning, on our drive down from Dam, we spot a man walking with a rifle in his left hand. He introduces himself as Asbel Kiptomoto. Though short in stature, he looks older than his 18 years. He says he, too, is a member of the KPR. Just two weeks ago, he was out herding what he claims were 400 cows—around 60 of them his, the others belonging to neighboring families—when a group of Pokot gunmen attacked. It happened right here, just feet from where we’ve stopped.

The attackers sent him reeling down the mountainside, fleeing bullets. Once he was far enough away, he says he spent some 80 bullets taking shots at the attackers from afar. Now he’s got only 10 left. The gunmen made off with all but 100 of the cows.

“If I found those guys I would kill them,” he says. “I would rather kill them before they take more cattle or kill people.” In fact, he’s already too late to prevent the latter. Kiptomoto is the younger brother of the security guard at Arabal Primary School who was killed on the job in January 2015.

Kiptomoto was a student at the time of the murder. Now he’s taken up his deceased brother’s line of work: he’s currently trekking down the mountain to collect children from a far away school and escort them home safely to their families. He does this each day, a sort of volunteer bodyguard for the children, not unlike his brother before him.

The rifle he’s carrying was given to him just one month ago by police. It’s a Hungarian-made AKM style weapon—an AMD-65 7.62 × 39 mm self-loading rifle, to be exact. But the stock has been replaced with a badly bent piece of metal, and it’s missing its distinctive muzzle altogether—a crucial part of the weapon’s accuracy. Moreover, the training he received in how to use it lasted all of a day.

I ask Kiptomoto whether the police—the real police—do much to engage the armed bandits, to try and arrest or disarm them.

“The police just patrol the roads,” he says. “They don’t leave the road—they’re afraid.”

As if to prove his point, as we’re speaking, an armored personnel carrier with a gunner on top rumbles past us down the road. It seems clearly out of place—a war machine surrounded by empty, dry mountainsides peppered with thorny shrubs. Its mission is unclear.

This February, Kenya’s Deputy President William Ruto said, “I have ordered police officers to shoot anyone stealing livestock whether in possession of a firearm or not and also anyone found with an illegal firearm will be shot on sight.” The fact that to assassinate people on sight might itself be illegal didn’t seem to bother Ruto. That such rhetoric probably has the entirely wrong effect, scaring off any cattle rustler who might be willing to turn in his gun in exchange for amnesty, seemed lost upon him.

Who is to blame for the violence in Arabal? Certainly not just the Pokot, as some would suggest.

“Majority of Pokot in Baringo are peace loving and development conscious and therefore blanket condemnation should not be applied. Let us call the terrorists by their right name. The terrorists,” wrote one blogger from the region, Samuel Cheraisi, of those carrying out the attacks around Arabal.

“What is sad about this is the Pokot get villainized as a group, when it’s only some individuals,” says Elizabeth Meyerhoff. That, she says, has changed little in the 35 years since she authored a National Geographic article about the tribe. But she says that in recent times, some individuals “have gone too far, with youth often taking matters into their own hands… Pokot have been raiding other tribes since long ago, but they didn’t kill women, and children,” she says. “The whole dynamic of that has changed since guns came into play.”

The Governor of Turkana County, which borders Baringo to the north, told the news agency IRIN that “continuing to treat [cattle-rustling] like a cultural practice is akin to condoning an illegal business. It has been highly commercialized and many politicians are now using it to create support zones for themselves.”

When I brought up the Marigat murders to one Pokot elder, he pointed out that “it was politicians who were killing each other”—not everyday people. He says that in the aftermath, “Pokot were misled to go kill Tugen in revenge.” Misled, he believes, by politicians.

“Rustling is a problem, but few people are thieves,” says the elder, who asked not to be named out of fear of reprisal. He says the Pokot who migrated from his area to Arabal did so not to steal cows, but to feed their own. The reason many Pokot now carry guns “is because of the negligence of the government in the past.” He points out that previous governments armed police ‘reservists’ from competing tribes. Many believe some of those same weapons have been used to attack Pokot. Perhaps when they heard about the assassination of their political leaders they became fearful. The thinking, he says, is that “if they can kill someone who is [powerful], of course they can kill me.”

He says if Kenya’s leaders had invested in the Pokot—had helped them manage land and given them funds to grow grass on it—his fellow tribesmen might never have had to migrate to Arabal in the first place.

Before the weapons arrived, there were small killings. Now people are dying in numbers

“Although there is small cattle rustling, that is not the main problem,” he says. “There is a negligence in our government. In other areas like Kiambu, children go to school. But in our area, nobody is providing water, education.”

As to Cornelius’s assertion that the Pokot see cattle rustling as inherent to their culture—part of the stereotype of the Pokot warrior—the elder admits that Pokot people still refer to other tribes as “enemies.” But he says Pokot youth are taught that killing is wrong. “The law of Pokot is, ‘if you kill somebody, you will be killed.’”

“In this community, when they fight or when they quarrel, they do not kill each other. They just use sticks to fight. That is our culture,” he says.

“Before the weapons arrived, there were small killings. Now people are dying in numbers.”

Anthony Langat contributed to this reporting.