One man is doing his best to keep rock alive—and inclusive—in Malaysia’s outlier island-state

On weekends, the pulsating heart of northern Malaysia’s music underground spurts blood from the first floor of a battered building along the shoreline of Georgetown on eternally gridlocked coastal thoroughfare Pengkalan Weld. Its ribcage—a black-tinged loft where Penang’s wretched rock and roll youth come together to mosh away their frustrations—is a do-it-yourself concert hall, rehearsal room and recording studio with the unambiguous name, “Soundmaker”. On weekdays, when the rest of Penang’s underground firebreathers douse off inside office cubicles, a man named Cole Yew is the only person keeping this place alive. A skinny, tattooed Malaysian Chinese, Yew is Penang music scene’s cardiologist. Whether he’s behind the mixing board, the bar, or on stage fixing up the backline, he keeps the heart of Malaysian rock red and beefy and always, always pumping blood.

Yew, 33, comes from Brinchang in the unrockable tea-estates of the Cameron Highlands, and spent the past eight years nursing underground subcultures on the island of Penang—the second largest urban area in Malaysia, and one that seriously lacked a musical action spot. It hasn’t always been the case: from the 1960s, Malaysia and Penang boosted a great number of western rock and roll-inspired bands called the “kugiran brigade”.

They played a fusion of surf-rock à la Shadows, and ‘60s British rock trademarked by the Beatles and the Stones. In the 1970s, Penang’s Indian-Chinese mixed combo the Alleycats reached international fame by signing to Universal and moving to Asia’s entertainment Mecca Hong Kong to perform for clubs and television. The problem started after heavy metal and punk planted serious seeds of musical rebellion since the early 1980s: as elsewhere, increasing music piracy and the consequential fallout of local record labels and the live music industry initiated the dry season of 1990s and early 2000s independent rock.

“Me, Wai Kong and Kash started Soundmaker to give performance space to local alternative bands,” says Yew, rolling a cigarette with imported Golden Virginia tobacco. Behind the flickering lighter, his mohawked, hollow-cheeked face kindles with decades of DIY knowledge. In fact, Yew has a lot under his belt: he has hosted hundreds of shows and alternative DJ set parties, plays guitar in Malaysian avant-garde-post-rock stalwarts Hui Se Di Dai, and runs Soundmaker as Penang’s truest patron of the music scene.

“I book all sorts of extreme and alternative bands who wouldn’t have a chance on the island’s mainstream stages,” he says as we sit in Soundmaker’s tiny control room, hidden between the club’s gig hall and rehearsal studio. It’s here that Yew mounted the computer-cum-mixing-board he used to record countless Malaysian underground demos and albums, and where he manages a tight schedule of weekend shows. “This year we started the Rebel Gigs series on Fridays. The idea is to foster an alternative weekend hangout, nurse Penang’s lack of spaces for hard and fast music, and give bands a platform to perform and launch their releases. In a mere four months, we had bands coming from all over Peninsular Malaysia,” he says as he quickfingers his metallic tobacco box to produce another rollie.

THE DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC DEVELOPMENT OF MALAYSIA CRACKED DOWN ON UNDERGROUND ROCKERS

In Malaysia, a multi-ethnic and multi-religious (but predominantly Islamic) nation, the importance of Yew’s efforts is different than it might be abroad. Partially, it’s because he’s an antidote to the venom of the Department of Islamic Development of Malaysia (Jakim), which cracked down on underground rockers in 2001 and 2006 based on their alleged “devil worship”. Jakim went as far as banning black metal music, arresting teenagers, raiding rock shows and record shops, and painting the whole underground music scene as a single immoral flame. On the financial side, musical instruments in Malaysia are subjected to severe import tax, and the few showgoers, like anywhere else in the world, expect access to underground shows to be cheap. “The police came only once, and luckily we didn’t suffer big consequences. What truly amazes me, though, is how local scenesters still don’t get [the idea] that in order to get more quality, they must come out to the shows, and pay the meager entrance fees. Without that kind of minimal support, we’ll all go belly up pretty soon,” Yew says as his face turns sour.

Part of the problem is the fracturing between the metal and punk genres, a real subcultural yin and yang. To complicate matters, in multiethnic Malaysia, even the music scene is often divided: the Malay majority, together with a fraction of the Indian minority, follows the tropes of western extreme sounds (think bands like Carcass, Napalm Death and Insect Warfare), while the Chinese mostly embrace a post-rockish third way (like Mogwai and Sigur Ros). This they blend with rock sounds imported from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The resulting musical smoothie tastes like a commixture of post-rock, punk and post-metal, it’s largely sung in Mandarin for a Chinese crowd. It makes for a unique case of Southeast Asian musical ethnocentrism.

This Malaysian Chinese alternative-rock scene developed throughout the second half of the 1990s in Kuala Lumpur thanks to the efforts of people like Mak Wai Hoo and his label and newsletter Soundscape. Its previous version, written in Mandarin with the title Huang Huo—“Yellow Fire”—was an obvious nod to Chinese cultural exclusivism. As it happens, Yew had learned off his underground 101 from Soundscape’s newsletters when he was a teenage student in Kuala Lumpur, before he ever moved to Penang.

AMPLIFIERS BREAK, PIPES LEAK, WE’VE GOT TO COPE WITH TERMITES IN THE WALLS

“I have to thank Mak and friends if I am the person I am today. There’s nothing racist about that: it’s just natural, [considering] the fractured social situation in this country,“ says Yew. Chinese learn from other Chinese, even in the way of rock. But things could be different in Penang. Besides being a hotspot of political opposition, Penang is also the only Malaysian state where the Chinese are the majority. Since its nineteenth-century heyday as a British colonial port, Penang has enjoyed tax-free trade. This brought a melee of different ethnic groups and cultures. Drifiting European sailors and adventurers, Mainland China’s businessmen, Armenian immigrants, Tamil and Punjabi Indian plantation workers, and the newly intermarried Malay-Chinese group of the Peranakan all came together in this steamy tropical hotpot.

Today, Penang’s kaleidoscopic cultural melange is still very much alive. “This is a small island-state with a smaller music scene that prompts people to mix more than in other Malaysian cities. Still, there aren’t many non-Chinese people attending Chinese rock gigs. The same applies for metal and punk audiences: people don’t support each other, and in the end, it’s always the organizers and venue managers who struggle to keep the boat afloat,” he remarks.

Running Soundmaker is surely no piece of cake: Yew is forced to charge rental fees for Soundmaker’s show room as there’s a landlord to pay, equipment to maintain, and premises to keep clean and functional. He kept a day job for several years before he could start to support his philanthropic rock and roll mission with the club’s meager earnings. “I’m starting to scrape off a profit now, but trust me: it’s never enough. Amplifiers break, pipes leak, we’ve got to cope with termites in the walls… this building is old and very hard to make over.”

Yew shows me a dishevelled part of the wall at the back of the stage. It’s from here that, during the rainy season, water seeps trough the building’s ceiling and onto the stage.

But thanks to his resourcefulness and a natural penchant for Black-n-Decker DIY, Yew transformed Soundmaker’s tattered building into the hippest underground club in Penang. He built up a small bar, refurbished the lighting system, and had local artists decorate the walls with graffiti. “Soundmaker is like a puzzle I’m completing piece by piece. As soon as money comes in, I invest in upgrades. We have already done a lot, and people are starting to see the difference. Now bands ask to play here because we have a proper PA system and a reputation for quality shows,” he tells me, as he stashes beer boxes behind the bar.

After all, Penang’s underground scene seems to be luckier than many, as its mentor has that great deal of integrity, which is sorely missing in a country plagued with endemic corruption. Despite the many hurdles, Yew remains convinced that rock and rollers can play a vital role in shaping Malaysian society. “I always believed that music can change the world, but you need to work hard to make it happen.”

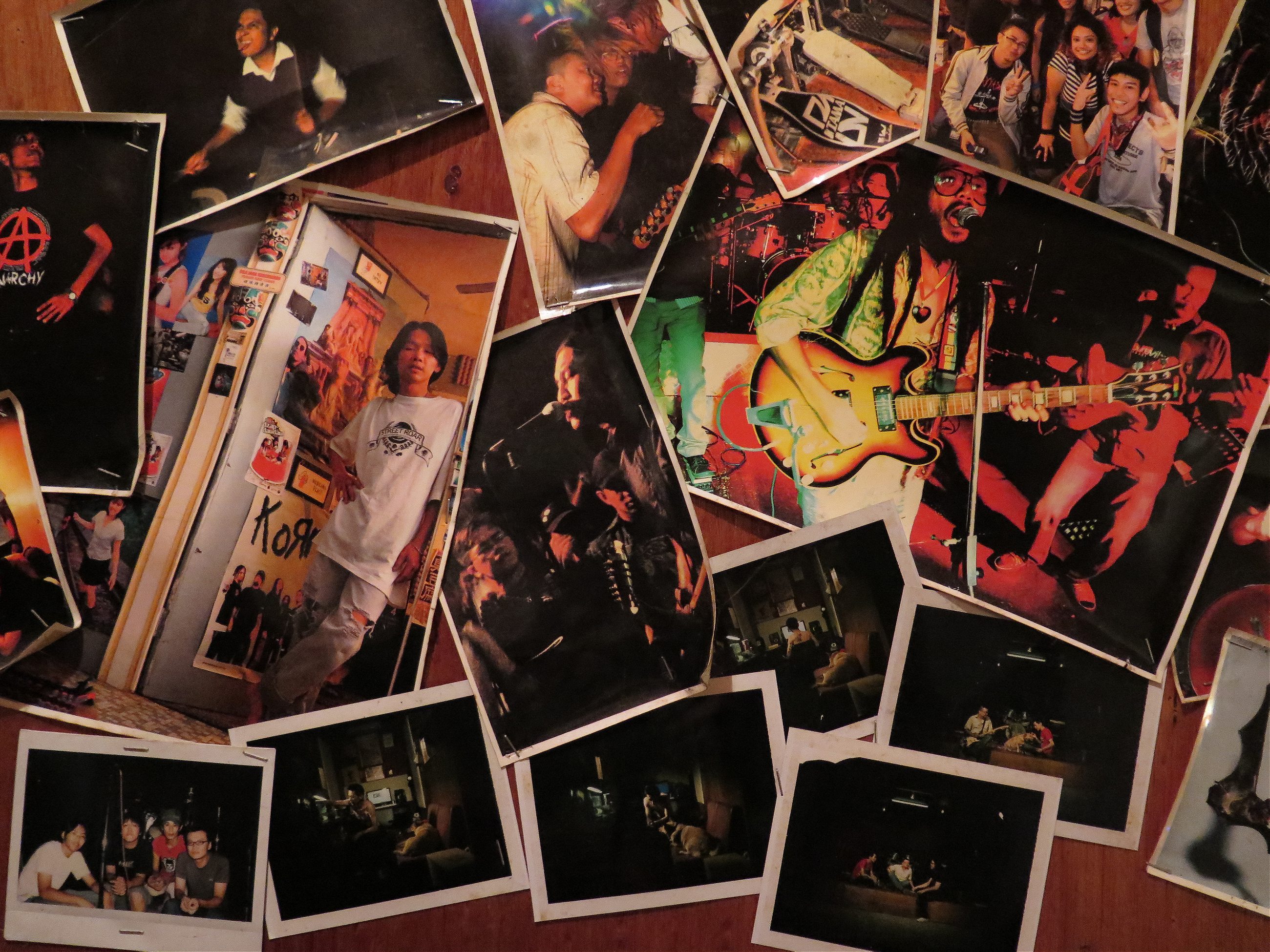

Top image: Jenn Wong