Gary Sullivan on the many Syrias represented in the bodegas of Brooklyn

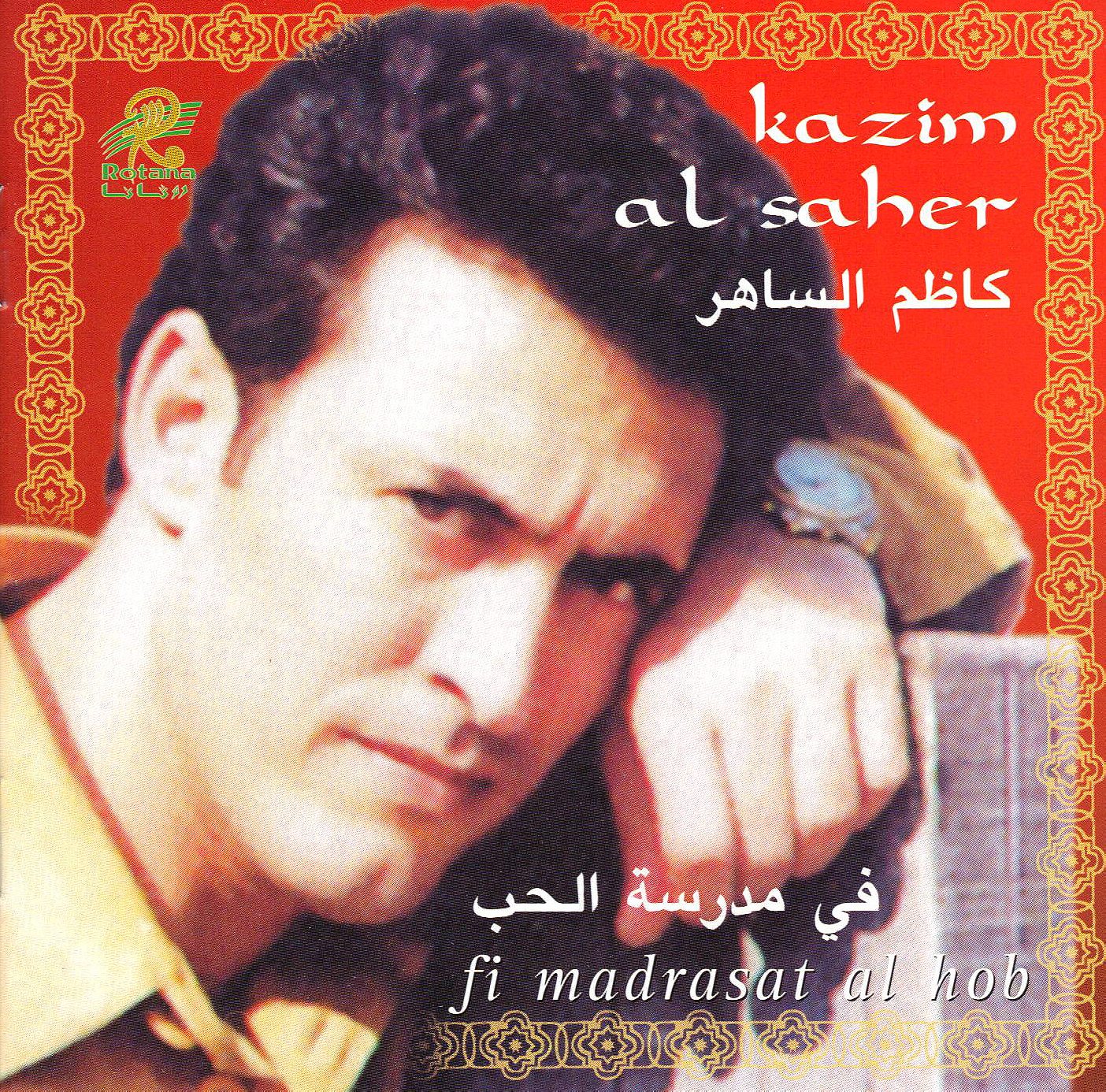

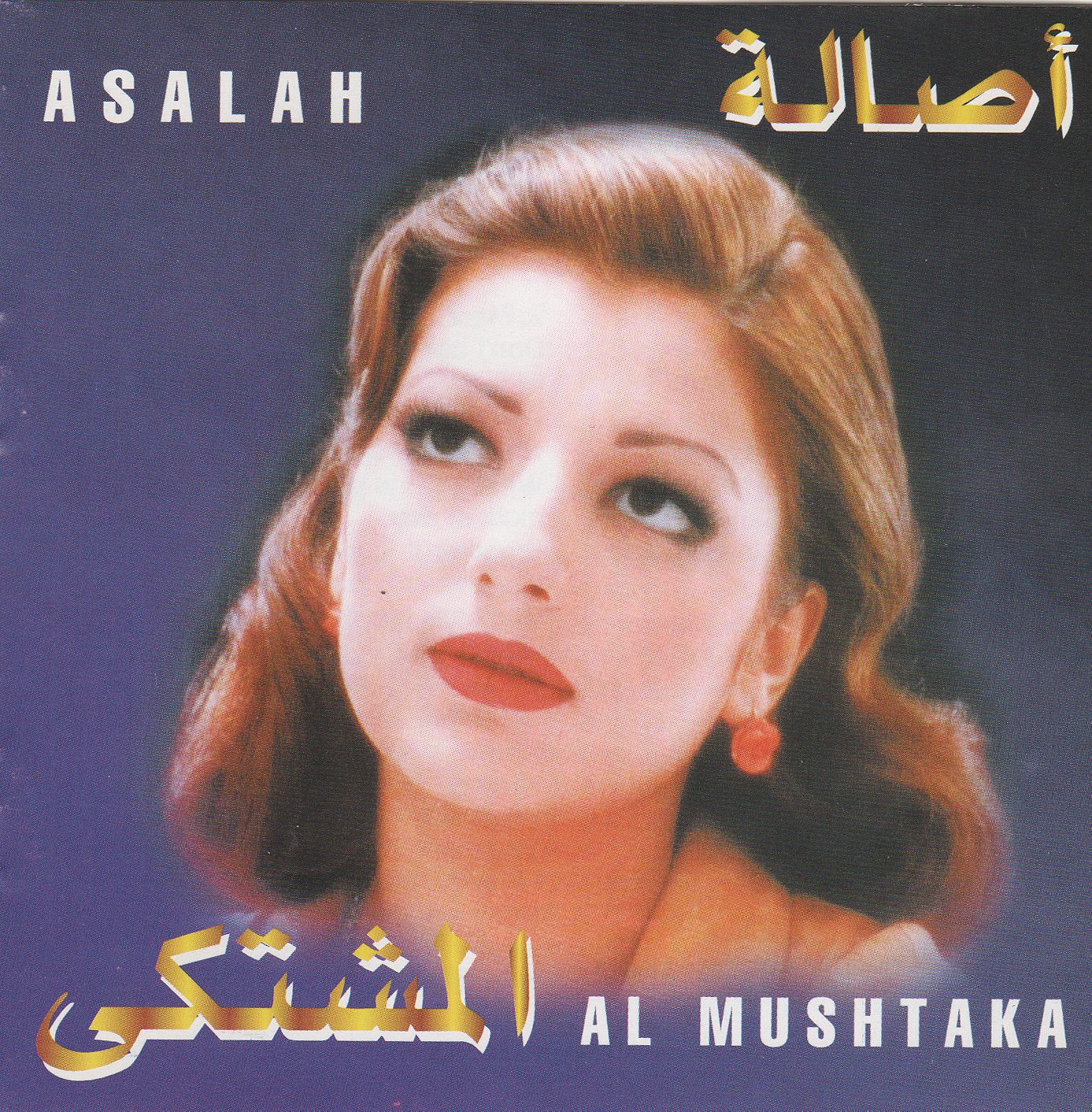

“Do you speak Arabic?” I looked up from the CD I’d been squinting at and sheepishly shook my head. The woman behind the cash register was middle-aged, with a warm smile. “If you’re going to buy just one, you should put that back and get Asalah instead.” I had no idea what she was talking about, but I wasn’t going to sacrifice the CD I held in my hands; the singer on the cover—with her loose, zebra-print headscarf, chunky black sunglasses and menacingly dark lip liner—looked as feminine and tough as the legendary Egyptian diva Oum Kalsoum. “That’s Najwa Karam—she’s from Lebanon,” my new friend clucked. “Asalah is from my home country, Syria. She is the greatest singer in Arabic.”

The clerk’s bodega on Fifth Avenue in South Slope, Brooklyn, wasn’t on my regular neighborhood beat. I lived in a first-floor apartment on 11th Street just off tree-lined Eighth Ave and avoided wide, gum-pocked, sun-exposed Fifth with its rent-to-own furniture stores and ’70s diners. Occasionally I’d venture down to pick up cleaning supplies from one of the avenue’s 99-cent stores. I must have been on such a mission that sweltering August day in 2000 when I saw the little Syrian bodega and stepped in out of the heat for a persimmon.

Depending on where and in what context you use the word bodega (noun, bō-ˈdā-gə), the word can refer to anything from the hold of a ship to a wine cellar or bar. In Chile, Colombia and Mexico it might be a warehouse or storage room, generally. Within the five boroughs of New York City, bodega almost always refers to a convenience store or deli that stocks essentials like toothpaste and toilet paper plus items of local ethnic interest—tomatillos, say, or tamarind paste. Although Spanish in origin, bodegas in New York are owned by and serve immigrants from all over the world, from Albania to Vietnam.

The Syrian bodega on Fifth Avenue was, for me, the beginning of a long love affair with a lesser-known product of bodegas: the music. For 3½ years I’ve been cataloguing what I think are the best finds—from bachata to Bollywood soundtracks—at BodegaPop.com. It’s a lo-fi approach to music, maybe, and there’s a lot of piracy behind the low prices. But like the rest of the chaotic, iconoclastic world of bodegas, there’s a lot of meaning behind the merchandise.

Only two physical reminders of lower Manhattan’s former Little Syria remain today. There’s St. George’s Syrian Catholic Church on Washington Street between Carlisle and Rector, the neo-gothic façade of which was designed in 1893 by the Lebanese-American draftsman Harvey F. Cassab. Next door sits the Downtown Community House, built in 1925 with financing from Bon Ami cleanser founder William H. Childs to, in effect, help scrub immigrants clean of their native customs and languages. The thousands of people who settled in this once-vibrant community, mostly Christians fleeing from the Ottoman–occupied Levant, were again displaced when a sizeable chunk of the neighborhood was demolished in the 1940s to make room for access ramps to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel.

In the 1960s, what remained of Little Syria was razed to become the site of the World Trade Center. (The cornerstone of St. Joseph’s Maronite Church—St. George’s main rival—was discovered in the rubble after the September 11th attacks.) Little Syria’s former residents dispersed throughout the TriState area, with many relocating to Paterson, NJ, or to Bay Ridge and Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. Sahadi’s Specialty and Fine Foods, which specializes in imports from the Middle East, originally opened as A. Sahadi & Co. in 1898 on Washington Street in Little Syria; Wade Sahadi (founder Abraham’s nephew) moved it to its current location on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn in the 1940s after the first wave of demolition.

There are some 75,000 Syrian Jews living in Brooklyn; they include some of the city’s wealthiest residents.

Syrian Jews, like their Christian counterparts, took root in Manhattan in the 1890s, but on the Lower East Side. Scorned by the already established European Jews, who called the newcomers Arabische Yidden and who doubted their Jewishness, the Syrians, or SYs (“ess-whys”) as they refer to themselves, moved on to establish tightly-knit communities across the river in Bensonhurst, Midwood, Flatbush and Gravesend. There are some 75,000 SYs currently living in Brooklyn; they include some of the city’s wealthiest residents.

The Syrian bodega clerk who gave me the music recommendations, however, was not likely one of the SYs. I suspect she was one of a handful of Syrian Muslims in New York, based in part on how far the shop was away from the closest SY or Christian Syrian strongholds, and in part on her fierce loyalty to the Sunni Asalah Nasri over the Maronite Najwa Karam. She took an immediate interest in me once I discovered the wooden case against the wall to the right of the cash register. Above the splintery, green-painted bin a sign read “CDs $5, 5 for $20.” It was the first time I’d seen—or at least noticed—albums in a bodega.

(Listen to Gary Sullivan’s Top Ten Songs from the Syrian Bodega.)

Time.com wrote last year that there are more than 13,000 bodegas in New York City. According to Gail Victoria Braddock Quagliata, a Brooklyn artist and art education major at Pratt Institute, there are at least 4,000 of these personality-rich mini-groceries in Manhattan alone. Quagliata began a conceptual art project at the end of 2012 to photograph every one of them; she completed her self-imposed assignment in late August of this year.

Quagliata started her project, she says, because she foresees the day when 7-11s have buried the last of these neighborhood touchstones, just as the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel and the WTC plowed Little Syria and its markets into history. Her concern has some merit; the Bodega Association of the United States claims that two or three of the mom-and-pop grocers go out of business every day in New York City—about 900 a year. In another decade, bodegas may be a thing of the past. The CDs and other recorded artifacts that collect soot in some of the more ethnically focused shops are practically yesterworld detritus already. Most places, if they haven’t dumped them outright, price them for less than cost. The Internet has made them nearly irrelevant for all but the poorest customers.

***

Najwa Karam was born in Zahlé, Lebanon, in 1966, to a family of Maronite Catholics. While no official census has been taken since the 1930s, Zahlé is regarded as the country’s third most populous city, after Beirut and Tripoli, and the city with the highest percentage of Christians (90%) in the entire Middle East. Its name is derived from zahhala, an Arabic verb meaning to slide or displace, though the city is known for its wine and poetry as much as it is for its landslides. Zahlé has been home to numerous poets over the years, including Said Akl, who may be the world’s oldest—he’s 102, though he hasn’t published in decades. Shakira has ties to Zahlé as well: her paternal grandparents emigrated from the mountain city to New York, where her father was born, before settling for good in Barranquilla, Colombia.

“Personally,” the clerk leaned over and said to me in a conspiratorial half-whisper, “I don’t believe the rumors about Najwa. She’s not Muslim, but this … this cannot be true.” My face must have registered as much confusion as it did surprise. “They say she named her dog after the Prophet Mohammed.” The tone of her voice betrayed not a smack of didacticism, but intrigue. What do you think? she seemed to ask.

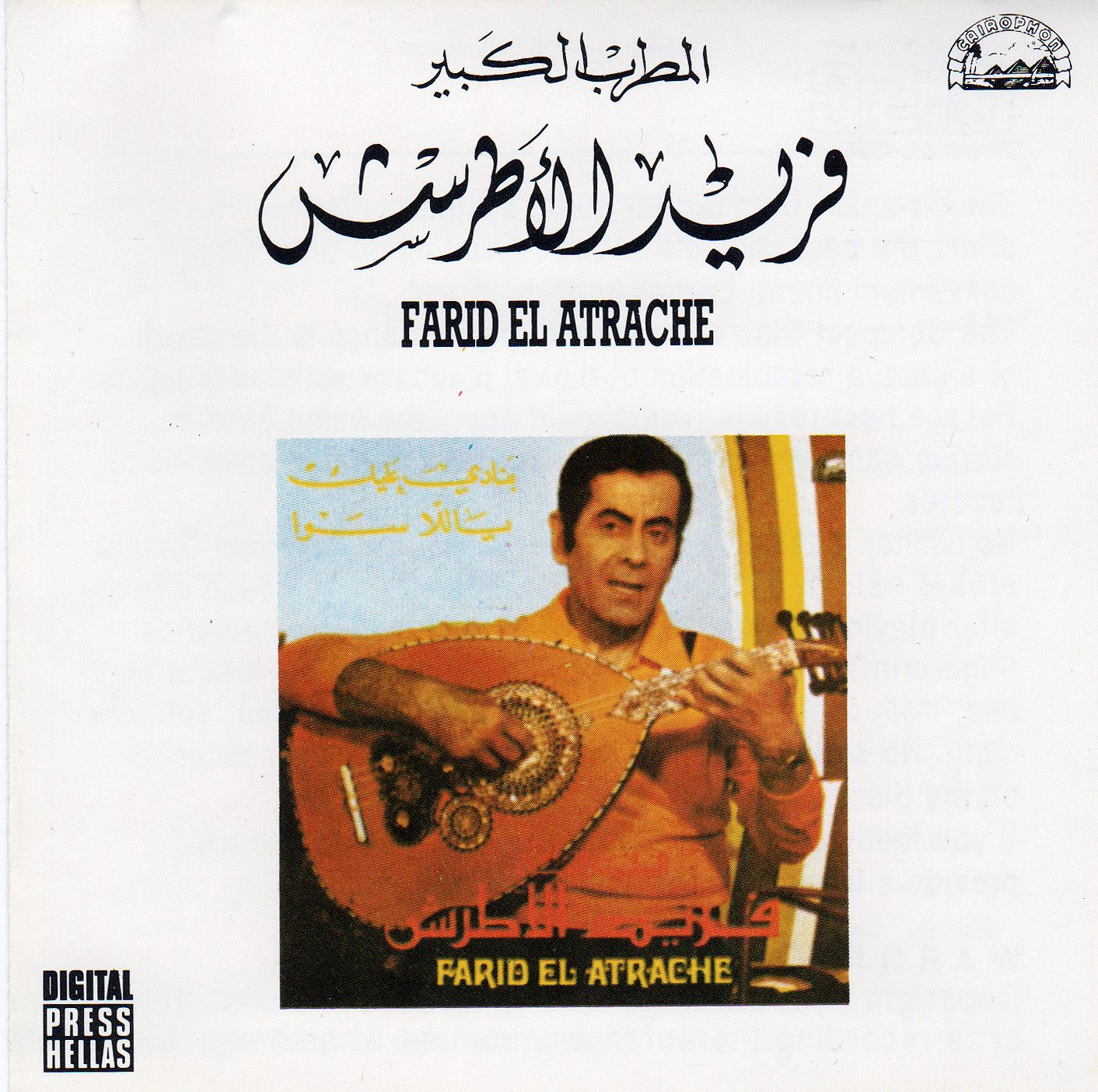

Before I discovered the Syrian bodega, I had been a somewhat frequent visitor of Rashid Music Sales—a bit northwest of South Slope on Atlantic Avenue and, later, Court Street in Carroll Gardens—where I paid an average $15 for Arabic CDs from everywhere from Morocco to the United Arab Emirates. Originally launched in 1934 by Albert Rashid in Detroit, Michigan, Rashid’s was once the largest distributor of Arabic music in the United States. Rashid’s first store in New York was on East 28th Street; he moved to Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue in 1947, following the rest of the exodus from Little Syria. Though the Syrian bodega’s selection was much smaller and narrower in focus than Rashid’s—nothing from anywhere west of Egypt, nor from any of the half-dozen Persian Gulf states—I couldn’t argue with paying a third of the price. It didn’t occur to me that most of the $5 CDs, including the one in my hand, were pirated. The thick-seamed and bubbling shrink-wrap job should have given it away.

A decade earlier, a Queens resident told a New York Times reporter that piracy was the only way he could afford rap albums retailing at $9.99. He had just bought five cassettes for five bucks each from a shop on Jamaica Avenue that, minutes later, was raided by the New York Police Department. The Recording Industry Association of America, or RIAA, had successfully lobbied a new state law into the books in November 1990 that made it a felony to possess 1,000 or more pirated recordings. RIAA made a point of pushing the police to enforce it. A few years later, the Internet made that particular law irrelevant. RIAA pushed for even stricter laws concerning online piracy. I remember going to a RIAA Lawsuit Party in winter of 2003 for the then-New York-based poet and photographer Tim Davis, who was being sued $10,000 for having in his possession 300 illegally downloaded songs.

Najwa Karam was in hyper-ascendency in 2000, when the bodega clerk first told me about the dog-naming scandal. Her 10th studio recording, Oyoun Albi, sold five million copies that year, making it the best-selling Arabic album of all time. It must have felt like karmic justice, given that the year before she’d been denied entry into Egypt, where she was scheduled to perform in Cairo—home to the largest music industry in the Arab world—as a result of the rumor then spreading around the region. (A Jordanian ex-prime minister issued a fatwa against the singer, which never wound up gaining traction.)

On January 14, 2011, Karam launched her television career as one of three judges on “Arabs’ Got Talent,” a fitting move given that her own musical career began in 1985 when she won the First Place Gold Medal on “Layali Lubnan” (“Lebanese Nights”), the Middle East’s first televised talent show. Two months later, on March 15th, 2011, a couple hundred protestors, spurred on by a Facebook page with more than 41,000 fans, gathered outside the Syrian embassy in Cairo to stage a “Day of Rage” and demand the resignation of President Bashar al-Assad, whose family had ruled Syria since the early 1970s. On the day I wrote this paragraph, the Syrian government launched what is generally considered the deadliest chemical weapons attack to date in the nearly two-and-a-half years of civil war, killing more than 1,000 civilian men, women and children in a Damascus suburb.

These songs and albums serve as reminders of the very real lives at stake in the region.

There are a lot of people, not so different from me, who are trying to make sense of what is happening in Syria, and what, if anything, the U.S. should do about it. Bodegas have nothing much to say about this, obviously; they offer the smallest of windows on other corners of the world. But if nothing else, these songs and albums serve as reminders of the very real lives at stake in the region that we seem to be ratcheting up to attack.

I moved from Park Slope to Ocean Parkway in early 2002. I often thought of the Syrian bodega and the friendly, welcoming clerk who had talked me into picking up what became many of my favorite Arabic CDs. When in the summer of 2010 I found myself returning to that stretch of Fifth Avenue to visit a new friend, I kept an eye out for the place, but it had vanished. I never learned the woman’s name.