This forgotten South African township has a secret motto that calls its old residents back time and again: “It’s all gravy.”

In 1966, my father was preparing to set sail from South Africa for India, where he would spend the next nine years studying medicine. The journey would take a month by ship and he knew he would not have the time or money to come home for a visit. After saying goodbye to his parents and nine siblings, he asked himself what else he would miss most over that decade. He ruminated on a last meal that would taste of home.

There are two places in the world my father talks about with visceral fondness. One is Mumbai, where he spent the majority of his student years, and the other is Marabastad, a multicultural township an hour away from Johannesburg’s city center. Once unflatteringly known as the “Coolie Location”, this is where my father grew up and frequented a dingy little takeaway shop called Mohideen’s, named for the dynasty of jovial Indian men who founded it in 1950 and whose descendants run it to this day. In saluting adieu to his childhood home, there was no doubt what my father would be eating. It had to be a saucy Mohideen’s steak sandwich.

Separate from the affluent, whites-only suburbs, Marabastad’s congested streets managed to house aspirants from within South Africa and beyond. Here, Africans, Chinese, Indians, and Cape Malays lived and worked together in what would be a peculiar mix in most other parts of the country. No small wonder, then, that it was in this setting that Mohideen’s gravy found its flavor.

Two thick slices of butter-grilled toast encasing spicy, gravy-soaked, tender steak with a side of even more gravy. Friends, you have not lived until you have dipped a buttery sandwich into a teacup full of meaty gravy without shame. Seriously, I can’t stop saying gravy.

“It tastes the same,” my father said as we munched on the dripping sandwiches more than fifty years after his pre-voyage last meal. “This gravy hasn’t changed since then.”

Looking around, you’d be forgiven for suspecting that nothing has been changed (or cleaned) since the ‘60s. Perhaps not even the cooking oil. But after one bite, you will be grateful for every speck of dust that may or may not have lent its flavour to that damned gravy. Whatever the recipe is, I’ll never know and quite frankly don’t care.

“The gravy comes from the steak itself, you can’t just make it with tomatoes and spices,” Hassan Mohideen explained. “It’s the meat that gives the taste and texture.

“We cook 15 kilograms of steak every day. You can’t get more gravy than that. Then there is a secret regarding the spices that is made by us in private.”

Generations later, my cousin Ahmed and I are still regular patrons at this joint. it’s a bit out of the way but worth a special trip. Other takeaway shops have tried to replicate the recipe, but to no avail. Apart from the iconic sandwich, another Mohideen’s favourite is the “Club Special”, a large box filled to the brim with every type of meat—processed or otherwise—a pile of chips, all soaked in yet more of that gravy, baby.

Ahmed and I tried a competing restaurant’s attempt at this box once, but it didn’t hold a candle.

“Something’s missing in the taste,” I said.

“I think it’s the spit,” Ahmed cracked.

See, we can joke about the hygiene of this restaurant knowing full well that we would happily eat chips off its gravy-caked floor if we have to. We don’t even object to the fact that the menu board famously doesn’t show any prices. Two people may pay vastly different amounts for the same meal, depending solely on how much the owner likes their faces that day.

Without songs and museum exhibits to speak of, Marabastad must be content with being immortalized in sauce.

Even for those of us that didn’t grow up in Marabastad, we have inherited nostalgia for Mohideen’s from our parents, partly because its food reflects one of the last semblances of a truly diverse community.

“It all started when my uncle and father, who worked in a blanket shop on this street, had the idea of going around Johannesburg, trying different food and then opening up a spot,” Mohideen said about the restaurant’s inspiration. “We’ve got customers of all types here, that’s the Marabastad tradition and that’s what people like. I want to revive that legacy.”

Like the more famous South African neighborhoods of Sophiatown and District Six, whose spirits have been memorialized in art, music, and museums, Marabastad’s diverse fabric also unravelled with forced removals through the apartheid government’s Group Areas Act. With its enforcement, the township’s residents were split up by race and moved into segregated locations.

Without songs and museum exhibits to speak of, Marabastad must be content with being immortalized in sauce. The incumbent Mohideen said people still come from all over the world, wherever they’ve settled, to eat his food.

“People that have left the country come back here to show their children and grandchildren where they grew up,” he said. “The other day a guy bought a bunch of our sandwiches, froze them, and took them to London.”

Here’s hoping I never have to travel that far.

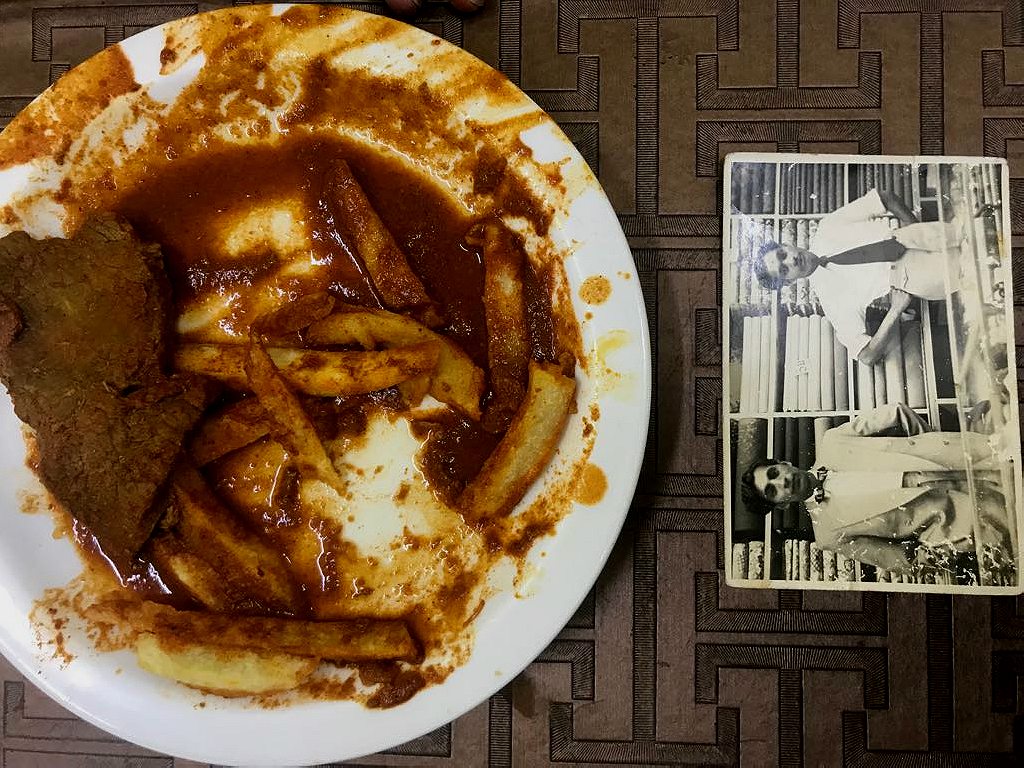

Top image: Two generations of Mohideen’s with a picture of the old Marabastad cricket team that frequented the restaurant.