Nepali cartoonist Rajesh K.C. talks about making political and social commentary for nearly three decades and raising his voice against those in power—from the country’s (now former) king to a powerful neighbor.

When Rajesh K.C. first started as a political cartoonist in 1993, Nepal had just emerged as a democracy from a one-party regime under King Birendra Shah. In the 25 years since, much has happened and changed in the Himalayan nation: it endured a decade-long civil war in which thousands of people were killed; monarchy, which thrived for centuries, was abolished; and its leaders rewrote the constitution, embarking on a new system of governance.

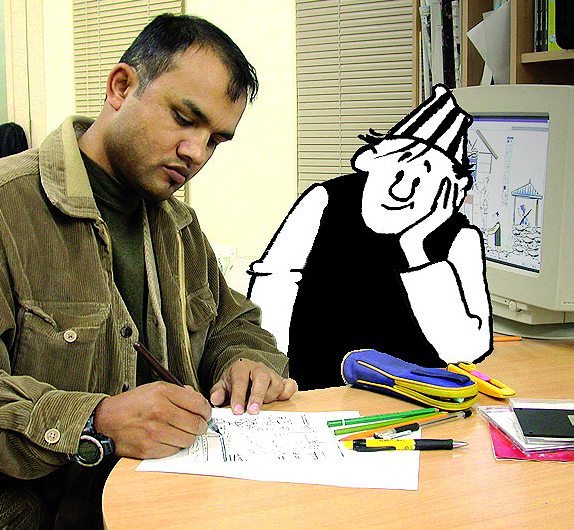

For an average Nepali, however, things have remained mostly unchanged. That is at the heart of the social and political cartoons by K.C., who, after at least 35 attempts to sketch a character, settled on Phalano—or “everyman”—one of the most recognizable cartoon characters in the country.

His cartoons express Nepalis’ frustrations and anger at their political leadership for their failure to deliver long-promised dreams as they resort to bitter infighting to hold on to power. K.C. says his drawings also highlight an issue that he thinks doesn’t get called out and challenged by the country’s leaders: meddling from India, its next-door neighbor, and biggest trading partner.

Today, in addition to drawing political cartoons for Baahra Khari and The Annapurna Post, K.C. focuses on his business venture: he owns a cafe—Phalano Coffee Ghar—and a clothing shop—Phalano Luga—in Kathmandu. R&K’s executive editor Anup Kaphle talked to K.C. about keeping an eye on his country’s—and its next-door neighbor’s—treatment of the common Nepali man.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Roads & Kingdoms: The protagonist in your cartoon is named Phalano. Tell us what that means and how that name came to be?

Rajesh K.C.: Phalano is the common man—he is everyman. I wanted to present the social and political absurdities in Nepal through this common man’s perspective. So, when I started my drawing career in 1993, I started with 36 different characters. The editor at Kantipur Daily at the time and I then narrowed down the list and settled on what became known as Phalano. The name of the character itself was suggested by journalist Kanak Mani Dixit in 1998.

R&K: What inspired you to become a cartoonist?

K.C.: One of the first cartoons I saw as a child was a caricature of India’s then prime minister Indira Gandhi—it was drawn by RK Laxman, whose creativity has been a huge inspiration for me.

R&K: Do you remember the first cartoon you ever drew?

K.C.: I don’t quite remember my first cartoon anymore, but one of the first political cartoons I drew was published in The Rising Nepal—Nepal’s first English daily—in 1991.

R&K: What was it like working for a government-run paper?

K.C.: Since it was a state-run media, my cartoons were heavily censored. Sometimes, when a cartoon was finalized, it used to take four days to get it published—they would be irrelevant by the time they were in the paper because our political situation was rapidly developing at the time. I was also regularly asked to remove captions from my drawings. I don’t remember the exact dialogue, but once it involved a cartoon about mounting pressures on political leaders for election candidacy.

R&K: Whenever there have been attempts to censor journalists and publications in Nepal, cartoonists have been able to get around them. What was it like in your newsroom after King Gyanendra took over absolute power in 2005?

K.C.: The morning of Feb. 1 when King Gyanendra declared an emergency and put leaders behind bars, his military generals sent me a message, essentially warning me against drawing cartoons that would hamper the security forces’ morale. Several top leaders and journalists had been detained, a number of newspapers had been shut down, and most communication lines had been severed, including the internet. There were about 100 heavily-armed soldiers stationed at our newspaper office. Military officers used to check each and every page before it went to the press and used to remove any material critical of the king or his government.

R&K: How you were able to talk about the censorship, and the house arrest of political leadership at the time?

K.C.: As a cartoonist, my challenge was to find a creative way to send the message to the public. I started creating cartoons using metaphors for issues about which journalists were prohibited from writing. The following day, I drew one cartoon illustrating a man running after an ambulance for his pregnant wife because the telephone line was dead. My other cartoon featured three top leaders under house arrest for weeks, trying to find a barber to trim their bushy hair. The other cartoon showed a journalist who sent his story via fax while a government officer was hiding under the table reading the story as it is being fed through the machine.

R&K: Which cartoon of yours has received the most attention?

K.C.: I’ve published more than eight thousand cartoons so far, so it’d be very difficult to pick a particular one that’s generated the most buzz. I will say, however, that most of my cartoons have been received well by readers. As a country constantly in political transition, Nepal is ripe for satirical cartoons, so they tend to get a lot of attention and praise.

R&K: Do you ever find yourself pausing to reconsider if a certain sketch is a good idea?

K.C.: Nepal is a diverse country in terms of religion, culture, and geography, so I have to be very careful while aiming for the bull’s eye. Whenever I draw a cartoon, I also have to draw a line of self-censorship, to make sure I’m not disrupting communal harmony.

R&K: Which is your most controversial cartoon?

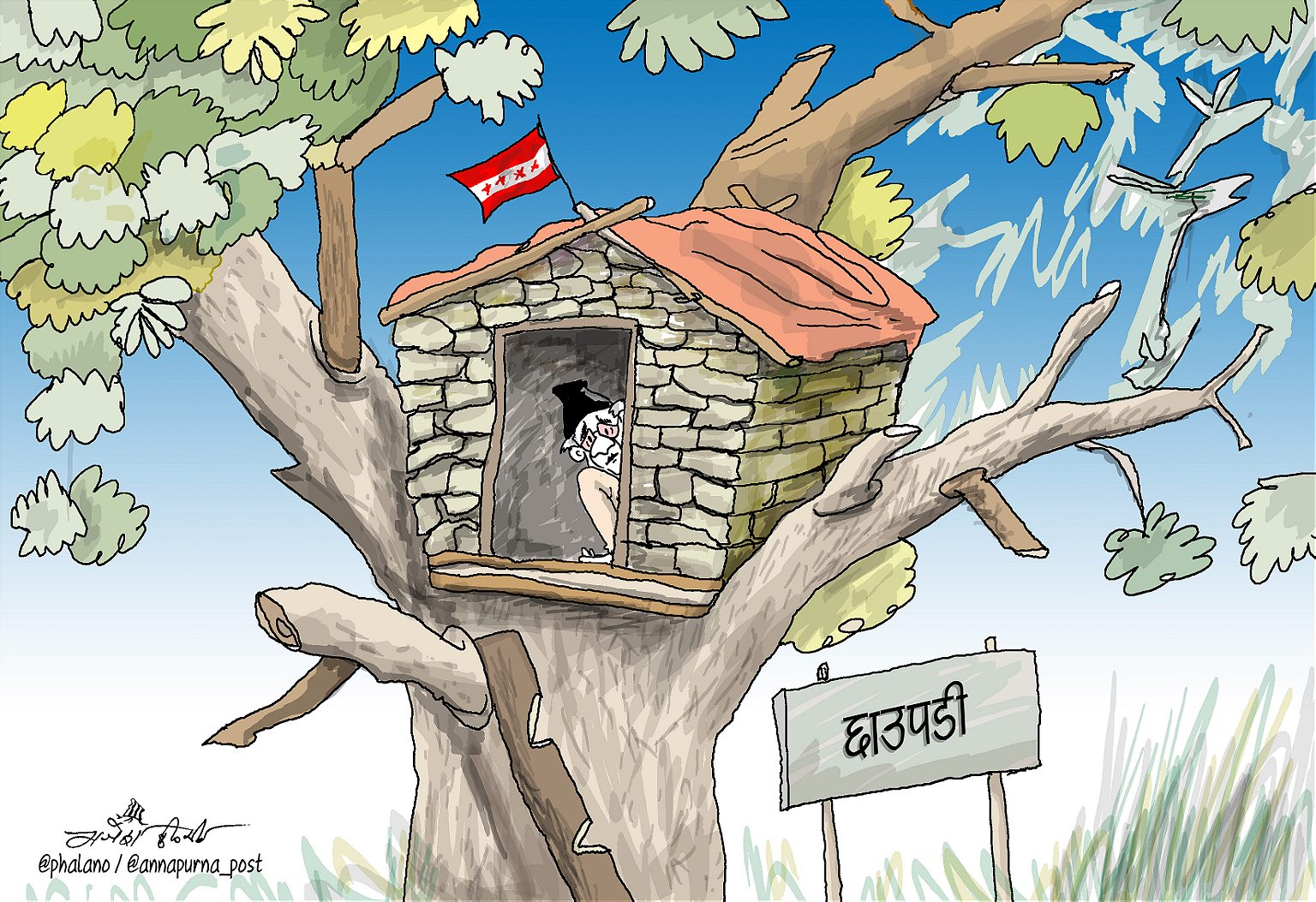

K.C.: There is plenty of dissent over my cartoons every day, but I don’t think there has been a severely controversial one yet. Recently one of my cartoons on Chaupadi—a tradition in parts of Nepal in which menstruating women are considered impure—received some criticism from feminists.

R&K: The cartoon you refer to shows a prominent Nepali politician inside a “menstruation hut” on a treetop. Can you talk a little bit about that particular drawing?

K.C.: Chaupadi is a social tradition that banishes women from their homes during menstruation. During this time, women are forced to remain inside a separate mud hut or in cowsheds that are in terrible condition, leaving them vulnerable to freezing weather, snake bites, and wild animal attacks. Despite the Supreme Court banning the tradition more than a decade ago, the practice continues in the mid-and far-western regions of Nepal.

R&K: What was your thinking behind combining that social issue with a political one?

K.C.: Sher Bahadur Deuba, the caricature in the drawing, has become our prime minister four times in the last two decades. Deuba, the president of the largest political party until this year’s elections, Nepali Congress, is also from the same region where the Chaupadi tradition endures. I believe that as someone who had held leadership of the country more than once, he must also be held accountable for not ending this heinous taboo. Then in the last election, his party, Nepali Congress, suffered a heavy defeat—and his party members and cadres pointed their fingers at him, holding him responsible for the loss. So, I tried to bring the two issues together in that cartoon.

R&K: A large part of your work also focuses on Nepal’s relationship with its neighbors. Why is that?

K.C.: As a landlocked country, we are heavily dependent in terms of economy and accessibility with our two giant neighbors. Our politics is influenced by both these two countries, but mostly by India. In recent years, India has tried to force amendments into our constitution. When that didn’t work, it imposed a blockade—and denied it had done so—while we were still reeling from a devastating earthquake. Nepalis were choked for nearly five months and suffered a lot, but India continued to ignore this. So, our relationship with India has been particularly fraught. with tensions. And most of our politicians do not complain when India twists our arm, so I feel like it is my duty to make the world aware of what the common man has to endure because of India’s actions.

R&K: In one of your cartoons, you show a character that looks like India’s prime minister Narendra Modi at the India-Nepal border, while a fuel truck drives past it. Do you think caricatures of Indian leaders are merely a sign of the times?

K.C.: The cartoon about Modi points out the inhumane nature of the blockade India imposed over Nepal. These kind of caricatures showing leaders from our neighboring countries are not only a sign of the times, but also an attempt to hold them accountable for their absurd actions.

R&K: Do you feel the same about Nepal’s other neighbor—China?

K.C.: Our relations with India and China are different. Our geography, religion, tradition, open borders, business interdependence, language, and history have brought India much closer to us than any other country in the world. Almost 90 percent of Nepali readers are aware of, and understand, major developments in India. So, my cartoons also reflect that neighbor—and its bullying of a smaller neighbor, which is either directed from the bureaucracy in New Delhi or the local administration and security forces in border areas.

R&K: Have you had to focus on India before as much as you do these days?

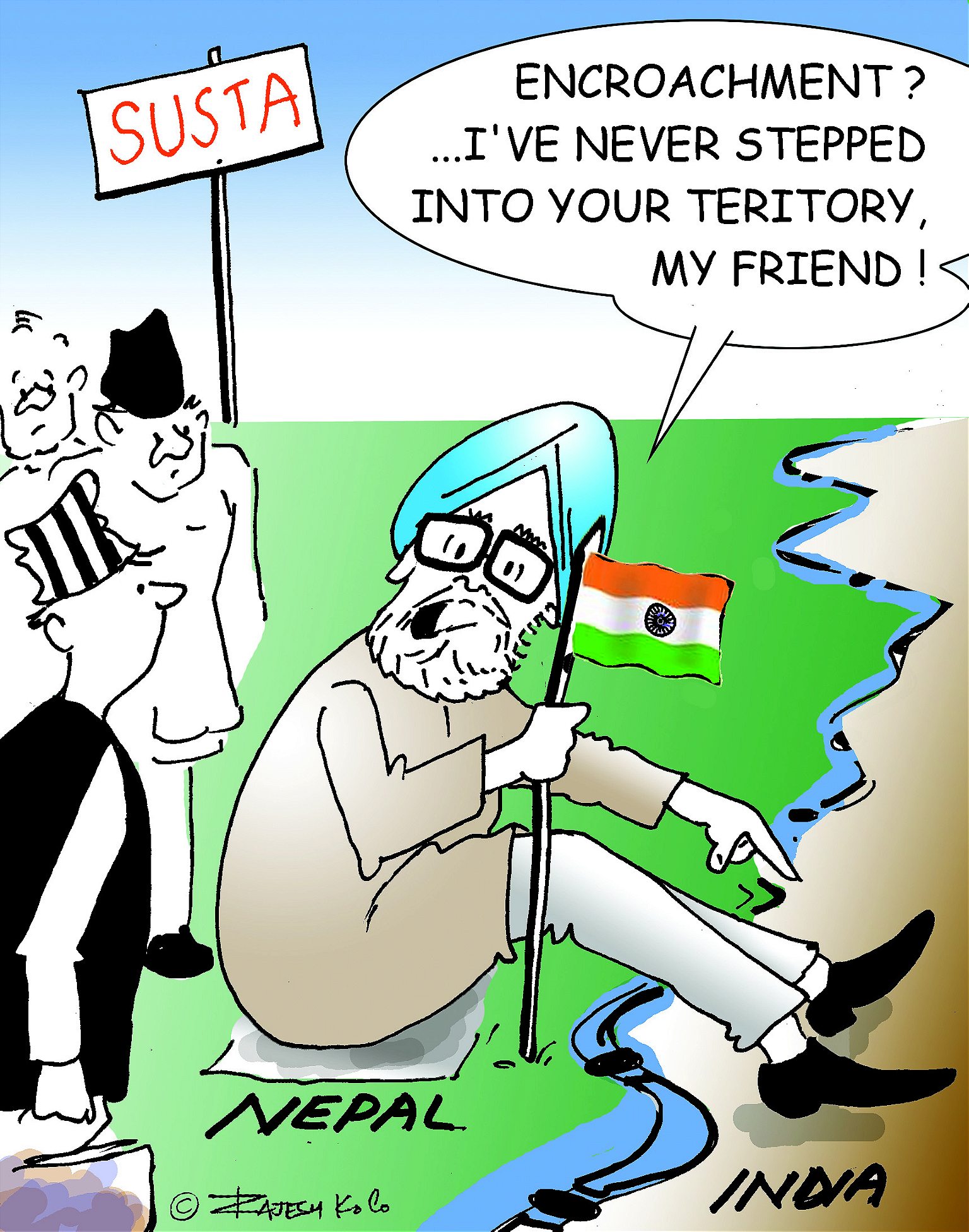

K.C.: I have been creating cartoons on our imbalanced relationship for decades. In 2008, I drew a cartoon to bring attention to India’s land encroachment on Nepali territory. The drawing showed the then Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh, sitting on the Nepali side while resting his legs on the Indian side, while claiming he had never stepped on our territory.

R&K: What kind of reaction did you get to that drawing?

K.C.: After the cartoon was published, Indian officials sent a letter to the editor. It said: “The cartoon carried on the front page regarding the alleged encroachment by India in the Susta area of Nepal is not only misleading but also in very poor taste, reminiscent more of the gutter press than the objective and respected newspaper that you doubtless want to be.”

R&K: You’ve been drawing cartoons for nearly three decades, but looking at a lot of your work, it’s hard to not feel like Nepal’s been at a standstill this entire time. What’s changed in 30 years, you think?

K.C.: Despite the fact that there has been so much corruption, turmoil, and instability—including the decade-long Maoist insurgency—Nepal has made demonstrable progress in the fields of education, media, and communications. These are the backbones of freedom and democracy. The pace of development in Nepal is slower, but the public awareness is higher than it has ever been before.

R&K: What hasn’t changed?

K.C.: The game of musical chairs among the top leadership of political parties has not changed at all.