In 1980, a gay man hid two journals above a light fixture in a stifling apartment in Tokyo. Thirty years later, an American teenager discovered it.

For eight months in 2014, I lived in a drab one-room apartment with three Mongolian roommates amid the skyscrapers of Nishishinjuku in central Tokyo. I slept on a tatami on the floor between the base of a bunk bed and the fridge, rolling up the mat each morning before my 20-minute bike ride to school. When you live in a space that small, the tiniest details become familiar: the slight slant of the window frame that kept the sliding panel from sitting flush during the frigid Tokyo winter; the Rorschach blots of mold in the bathroom; the exact number of dishes that could fit, creatively stacked, in the tiny sink. One day, after five months of living in that space, I discovered that it had been hiding a story all along.

That morning, I had overslept, so I left for school in a hurry, leaving the hot water running in the bathroom sink. When I returned, the circuit had blown. Standing on the toilet with his head through the ventilation panel in our airplane-sized bathroom, Altai Ogtonbaatar—a resident of Tokyo by way of Ulaanbaatar—found a dusty stack of books tucked away in the ceiling. It was a vintage issue of the Japanese gay magazine Barazoku, and two journals with serene, watercolor covers, written between 1980 and 1984.

The diaries belonged to Noriyuki, a young gay man who had lived here alone, in the sixth building of the first street of the fourth subdivision of Nishishinjuku nearly thirty years ago. They were signed “Sugar Boy Yuki.”

[This is what it’s like working torturous hours in Japan]

To situate Noriyuki in our matchbox of an apartment, you have to go back to well before my birth—or his—to wartime Japan. After the devastating finale on the Pacific front, U.S. troops under Douglas MacArthur assumed administrative authority in Japan, taking control of military facilities across the islands, including those in central Tokyo. The soldiers, many of them veterans, brought SPAM, root beer, and a soldierly longing for warm beds and bodies. And so, as in many military towns, a red-light district sprung up and flourished. Called akasen, or “red-line” in Japanese, (the use of ‘red’ is coincidental), the brothels were legal, regulated, and clustered in Shinjuku Ni-chōme, the second subdivision of Shinjuku Ward, a 20-minute walk east from our apartment.

Prostitution in Ni-chōme thrived under the American occupation, but as Japanese women exercised their new rights to political participation, the democratic ideals that the soldiers were ostensibly around to cultivate took root, resulting in women’s Christian groups lobbying successfully for the passage of an Anti-Prostitution law. Passed in May of 1956, the law didn’t take effect until April 1958, but it sounded the death-knell nevertheless for the akasen business (unregulated prostitution, called aosen, or “blue-line,” slipped through the statutory cracks). When the brothels closed, the sex-workers departed, too, leaving behind a neighborhood tainted by the stigma of impropriety. To take their place came another marginalized group: LGBT people.

[Thousands die alone in Japan every year. This man cleans up what’s left behind.]

By the 1980s, when Noriyuki would have frequented the gay bars and coffee clubs of Ni-chōme, the area had become the center of gay life in Tokyo, and, by extension, Japan. In a city of mosts (most restaurants, most people, most vending machines), Ni-chōme was no exception, boasting the highest concentration of gay bars, clubs, and cafes in Asia—over 300 crammed into five square city blocks. For young gay men like Noriyuki, it would have been the center of the world.

These days, with the rise of internet dating and the greater acceptance of gay rights in Japan, Ni-chōme’s role as a rare safe space for LGBT Japanese has diminished, although it is still the premier LGBT nightlife district in the country. During the day tourists and businessmen frequent the bookstores and street-level ramen joints. In the evening the bars come alive.

I read Noriyuki’s journal zealously, setting up shop for hours at a local Shinjuku sutaba—Japanese short for Starbucks—with a dictionary of Japanese slang open on my laptop. Noriyuki, it appeared, had come to Tokyo from Asahikawa, in Hokkaido, Japan’s cold northernmost island, at the age of 17 in 1978. By 1980, he’d found a job at a gay host bar, an iteration of the peculiar Japanese institution known as the hostess club, itself a cheaper, grittier iteration of geisha culture. His first journal entry, written on February 22, 1980, at 7 a.m. (a host typically works all night), begins: Today after a long time, a lovely customer came in and I was happy.

Japanese hosting culture is something that few foreigners understand, a state of affairs that the Japanese are in no rush to rectify. At many establishments, foreigners, regardless of their proficiency in Japanese, aren’t allowed inside. Customers pay steep covers to enter and socialize with a host or hostess for the evening—an attractive, perfectly coiffed and made-up young man or woman who will pour their drinks, sing their praises and make enthusiastic, if impersonal, conversation. After a few visits, a customer is expected to pick a tantou, or a particular host or hostess who will receive the money he spends at the end of the night. As a result, hosts are in constant competition for clients in order to accumulate earnings, listed on a leaderboard that’s sometimes posted outside the club. Sex is not officially sold; unofficially, it just doesn’t take place on the premises.

Like other cultural phenomena in Japan, the clubs are simultaneously conspicuous and ignored. In some parts of Tokyo, bleach-blond hosts with exquisite guy-liner and spiky, windswept hairdos smolder at you from billboards and posters, and yet most visitors will never set foot in a host club. The hosts, particularly women and gay men, are stigmatized for what is generally seen as improper work. Straight male hosts at clubs catering to women are, naturally, exempt from most of this judgment.

Noriyuki did not enjoy his job. Deciding when and how to quit was a major preoccupation in his journal entries for well over a year. He wrote about his struggle with workplace politics and his lack of friends outside of work. There were never enough handsome customers and always too many middle-aged ones, he wrote. Money was consistently tight.

His journal was also overwhelmed with worry. He worried about getting older while reading a letter from his younger brother in Asahikawa. He went to a four-dollar movie and worried about finding a boyfriend. He woke up to an earthquake, switched on All Night Nippon, and then worried about paying his rent. He wrote down somber poems by Fumiko Nakajou, a war-time tanka poet from Hokkaido who wrote about slowly losing a battle with breast cancer.

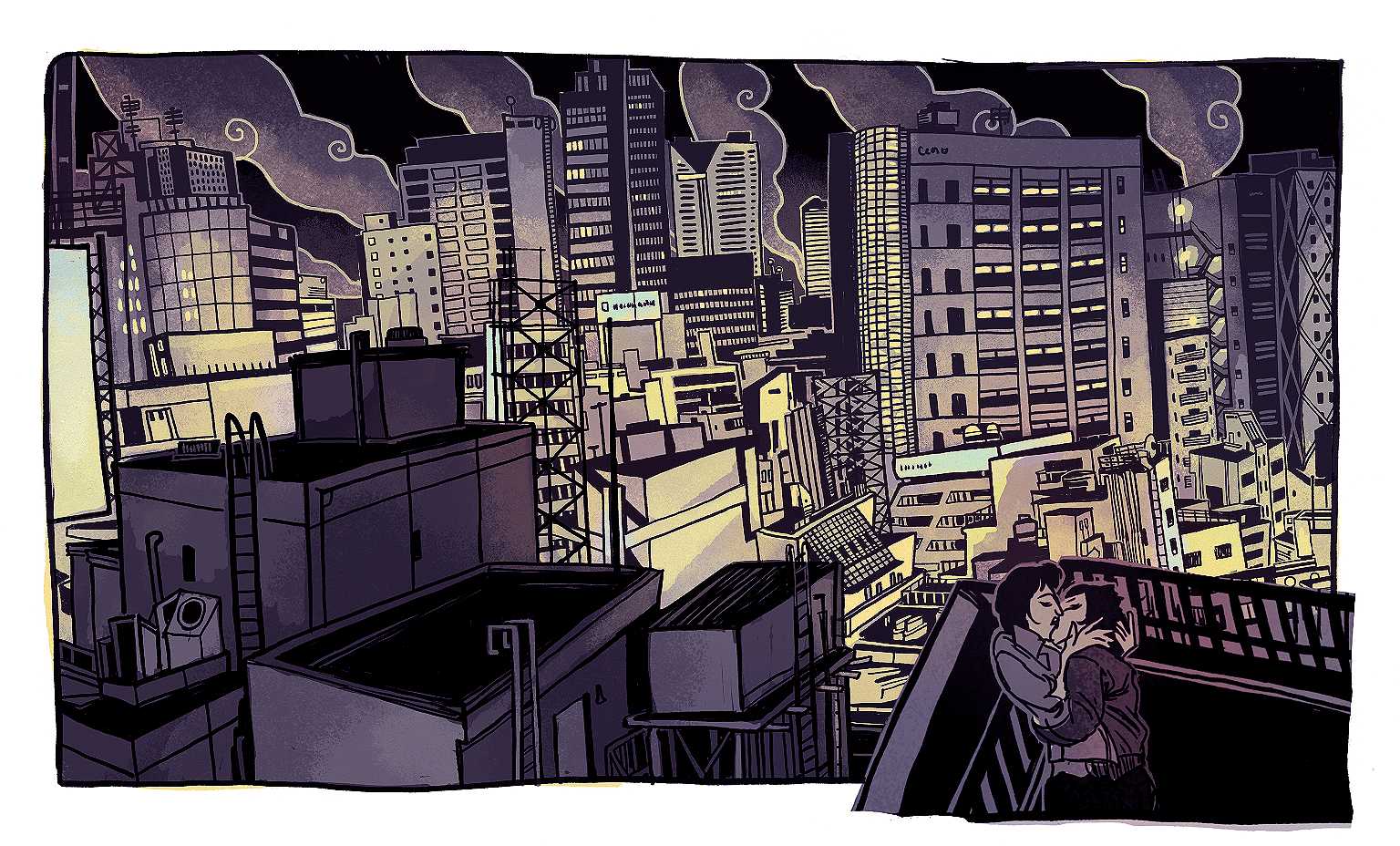

Amid the general malaise, certain entries stood out. In one of his entries, Noriyuki nonchalantly described having sex with a foreigner for money. On another night, another foreigner followed him home. The man had gotten on his train and they made lasting eye contact. They both got off at Noriyuki’s stop. He was speaking in English and I got the gist of what he was saying—let’s do it. Noriyuki’s roommate was home that night, so they moved to the roof.

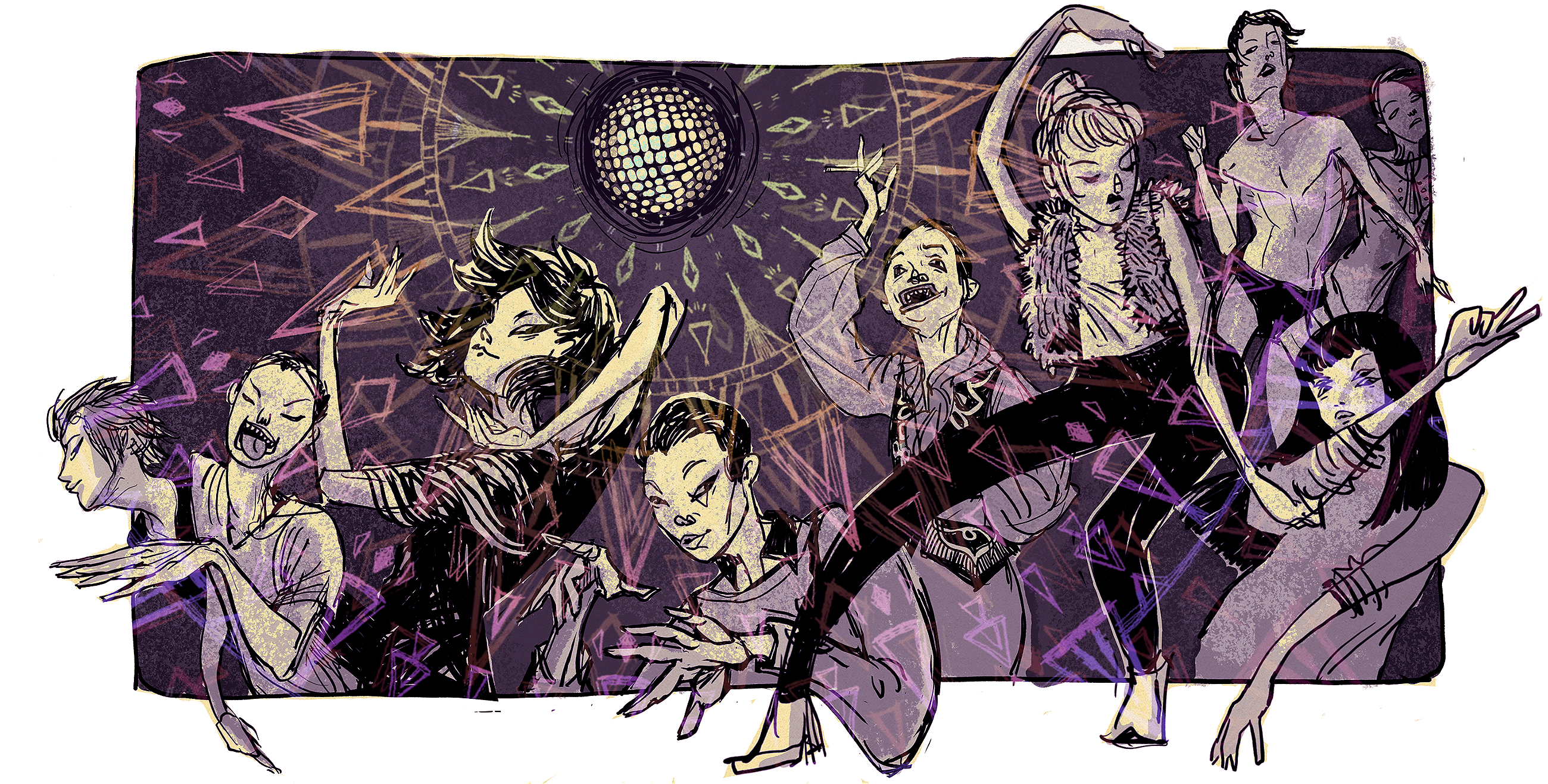

Noriyuki’s idea of fun was to take drugs—usually speed, acid, or MDMA, always euphemistically described as “medicine”—and go dancing at his favorite gay disco in Ni-chōme, New Sazae, which is still around today, half a century after opening in 1966. These days New Sazae and its effervescent, crisply dressed bar-master, Shion, who plays ‘70s and ‘80s disco for a middle-aged, not-entirely-gay crowd, have the aged grace of institutions.

Eventually, Noriyuki quit the host bar and went to work in the Roppongi district at a “new half” show pub called Sugar Boy, the source of his nom de plume. “New half” is pejorative Japanese slang for a guy in drag, the “new” type of “haafu,” a term used for a biracial, half-Japanese person. The new job didn’t seem to be all that much better and, after a yearlong stint, Noriyuki moved to another drag bar in Shinjuku called Garcon Pub. He flitted back and forth between Asahikawa and Tokyo. He missed his brother when he was living in the capital, and he missed the city when he went home.

In an odd, tenuous sense, Noriyuki’s life and my own seemed closer than the 8,000 miles, 40 years, and two languages that separated us. I, too, had moved to Tokyo at 18 (from San Francisco)—and had started to keep a journal just to hear the echo of my own voice. I found a grueling job at a restaurant that I quickly grew to hate. Agonizing over quitting, I was buoyed somehow to know that Noriyuki, too, had once struggled to navigate petty disputes at work and an overbearing boss. In a city that can be full of life, but also terribly isolating, I was also lonely.

On April 9, 1982, Yuki waited for a date beneath the gargantuan, multicolored video screen of Studio Alta in Shinjuku. The object of interest, a young man by the name of Koide, was due at 7 p.m. Like the Hachiko statue in Shibuya, the Studio Alta sign in Shinjuku was, and is, a popular meeting spot for young people, which means you are always trying to pick your friends out of a crowd. There is something uncanny about waiting for someone at Alta; one gets the sense that everyone is waiting for something to happen.

Two days earlier, Yuki had written about the meeting hopefully:

I don’t know why but I can’t sleep. I can’t stop thinking about him. I wish it would be Friday already. I haven’t felt so excited and happy in years. What should I wear on Friday? Will he actually come? In front of Alta? Maybe it is only for this day, this time, this hour but “La vie en rose!” How long will this last, this happy feeling?

I continued to read, wanting things to work out for Noriyuki and Koide, but the torn pages and blacked-out entries filling the second half of the second diary suggested that it may not have been a happy ending. Reading further, I saw that indeed the romance was doomed; Noriyuki and Koide suffered from a classic mismatch of expectations, casting Yuki into a deep despair.

That’s when his entries started becoming infrequent. He wrote that he wanted to quit his drug habit, but never seemed to manage it. He scribbled canted, inky drawings of belly-up fish, then sometimes blacked them out. At one point he contracts an STD, wonders if it might be syphilis, then stops writing for two years. In his final entry, a single page after two years of silence, he is seeing a married man while still taking drugs. The remaining pages are ragged where they have been torn from the binding.

None of my roommates seemed nearly as engrossed in our discovery as I was. Ogtonbaatar, whose keen eyes had spotted the dusty stack tucked in the corner, had opened the first book, ascertained it was some sort of journal, and shut it with superstitious flair. The secrets of others, he said, were not to be disturbed. Maybe it was the American in me, but I couldn’t help but want to know more about this man, to catch a glimpse of Tokyo through his eyes. Angar, Ogtonbaatar’s slight-framed best friend, would stand by the open window chain-smoking and listen while I read Noriyuki’s journal aloud.

Once I finished reading the journals, I couldn’t get Noriyuki out of my head. I needed to know: Did he still take drugs? Had Koide ever come around? Had he discovered a cure for the youthful angst we shared?

I called the city municipal office of Asahikawa, trying to finagle my way into public records that I was certainly not allowed to see. I explained my request as the man on the other end of the line listened with characteristic Japanese patience, unwilling to interrupt. Finally, he said softly: “Noriyuki, right? There are many Japanese with the same name.” He wished me a nice day and hung up.

Less than a month later, I left Tokyo. I have never returned. I don’t think I will ever find Noriyuki, but I still think about him, especially when I am home in San Francisco. Did he, like me, finally leave Tokyo and its concrete gloom? Or does he still spend Friday evenings under the neon signs, waiting for something to happen?