Pakistan’s national cake is a German import, adjusted to the palate of the Subcontinent, and a powerful symbol of middle class aspiration in a troubled century.

I landed in Lahore shortly after Pakistan’s most recent general election, whose victor’s campaign was based on the promise of a Naya Pakistan–a New Pakistan. At the airport, I was greeted by the sound of a guy going off on someone, screaming that this—whatever transgression had been committed at baggage claim—won’t pass in the New Pakistan. It seemed like a fight straight out of the Old Pakistan.

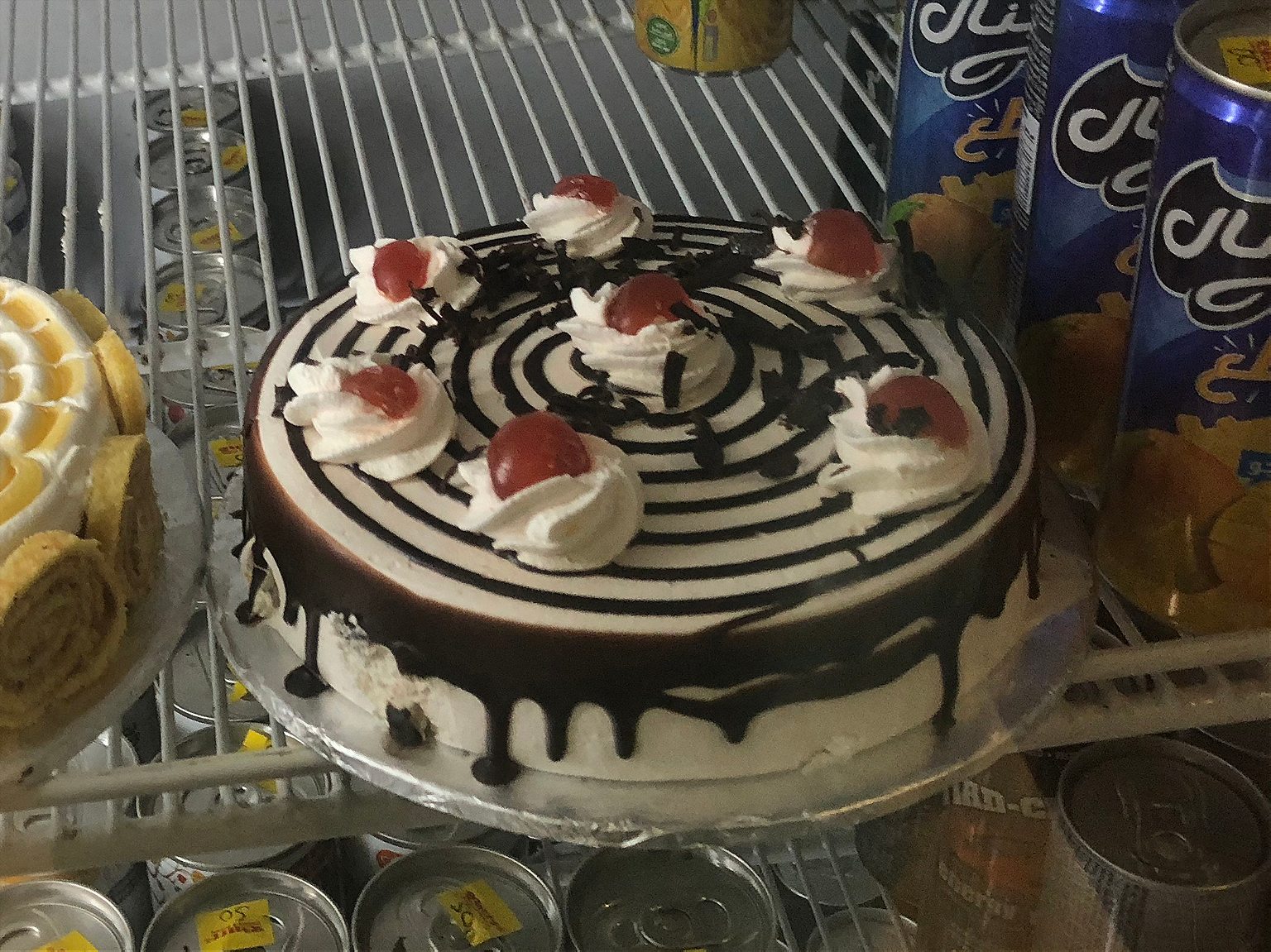

Whether there is a new Pakistan or an old one, or a just muddling-somewhere-in-between Pakistan, some things will never change. Someone will pick a fight at the airport within minutes of landing. You will encounter a relative insistent on propagating conspiracy theories. And at your neighborhood bakery you will inevitably find a Black Forest Cake: a cherry-festooned, chocolate-laden sponge, lathered with a sickly-sweet layer of white cream.

If Pakistan had a National Cake, this would be it.

Dessert trends have come, made it big, and gone, from doughnuts and frozen yogurt to lava cakes and gelato, but black forest cake has no rival in its ubiquity. Black forest cake is sold in old bakeries like Lahore’s Mokham Din & Sons, which opened in 1879. It has spawned businesses like the Karachi bakery Sacha’s. Even Khalifa Bakers in Lahore’s historic Mochi Gate neighborhood, whose fame centers around its naan khatai (flour, butter and nut-laden biscuits), stocks its freezer with black forest cakes.

Black forest cakes can weigh a pound, or two, or four, and are also sold by the slice. An expensive version is sold at the Marriott and cheaper versions abound in Lahore’s Mughal-era neighborhoods. The Facebook page for the Pearl Continental hotel in Peshawar features a video of its chef icing a black forest cake, and at Arabian Delights–a dessert shop in Lahore that sells baklava as well as Pakistani sweetmeats–there is a ‘white forest cake’ on display, sans chocolate flakes. At Shezan Bakery, where I stopped on a whim on a recent trip back to the city I called home from age nine to ten, and where I return to on vacations that get extended out of sheer laziness, the staff told me they sell three to four full cakes each day and as many as three times that during Eid.

I could be anywhere, in any bakery, in any city in Pakistan, and I would inevitably find myself staring at a black forest cake.

The original black forest cake, made with sour cherries and cherry brandy, was created in Germany around 1915. According to the Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets, the cake is most often credited to the pastry chef Josef Keller, who created it while working at the Cafe Agner in Bad Godesberg, a spa town south of Bonn. The halal Pakistani version does away with liquor, features sickly-sweet canned cherries, and is typically studded with chunks of tinned pineapple or peaches. To make it even more Pakistani, you can get your black forest cake topped with mango.

While not all black forest cakes are created equal, they have one thing in common: they are awful. There is no reason for a cake to be drowning in cream. The sponge cake itself tastes like styrofoam. There is too much chocolate. The pineapple is bitter. It’s difficult to fathom why—of all the dessert trends that have come and gone in Pakistan—the black forest cake has endured, or why it’s still popular.

Since the first time I encountered an inexplicable chunk of pineapple embedded in a slice, black forest has been a part of my life. I have eaten more slices of black forest cake than I’d like to admit, politely declined second servings during social visits, burrowed through the sponge to dig out the offending pineapple, and spooned the cream off a slice for my cat, all the while wondering: why do people like this cake?

They’d travel around the world, see it, and then eat it here.

For a long time, I assumed that it had to be because of the copious amounts of cream: after all, Pakistanis love dairy-based desserts. Or perhaps it’s because it looks rather elaborate, with the cherries and cream and chocolate shavings. Maybe it was a factor of its ubiquity or just of its foreignness.

Cake, after all, isn’t really part of Pakistani tradition. Pakistani cooking revolves around the stove top and the tandoor. Colonialism brought cake to the region, and in the early years of Pakistan’s independence, finally won in August 1947, cakes and baking were the domain of the elite, says Mohammad Qasim at Ajmer Bakers and Confectioners, opened by Qasim’s father, Mukhtar Ahmed, in 1952. Ahmed learned the art of bread and cakes in the last years of the Raj, when Pakistan and India were, a yet, undivided and still under British rule. When Ahmed opened Ajmer Bakers in Lahore’s up-market Gulberg neighborhood, his business catered largely to the city’s wealthier residents.

“Rich people used to eat [cake],” Qasim says. “They’d travel around the world, see it, and then eat it here.”

Ajmer Bakers made buttercream cakes, selling 15 to 20 in a day and hundreds over Eid, as well as elaborate wedding cakes for the city’s Christian minority. Qasim, who is now 61, started working at the bakery when he was a teenager. He wanted to study, but his father—fed up with workers stealing from him—fired his employees en masse and roped in his children instead.

Related Reads

In lower-middle-class neighborhoods—like the kind Qasim grew up in, or where my family lived—there wasn’t a big tradition of bakeries or cakes, even on birthdays. But in the late 1970s and 80s, as bakeries began to spread, cream cakes became increasingly popular in more urban neighborhoods. “They started making things with all kinds of cream. Things became cheaper, people started eating it,” Qasim recalled one evening, as he bagged purchases for customers. The neighborhood bakery would go on to become a local institution, where you could get basics like eggs, milk, and bread, and fresh ‘patties’—a flaky pastry with a chicken filling—as well as your cream-laden cakes.

Starting in the early 1980s, as more Pakistanis started traveling and immigrating, people would return from trips abroad and tell Qasim about a couple of cakes that they’d tried: coffee cake and black forest cake.

While coffee cake is still a niche choice, black forest cake took off. Qasim couldn’t explain why. “Because people are lakeer ke fakeer”–blind followers–“they don’t know anything.”

The cult of the black forest cake was born, fueled by the rise of neighborhood bakeries and bakery chains like Shezan and Gourmet, and by urbanization, as people began to move away from traditional breakfasts and eat more bread and eggs made available by bakeries. By the 1990s, a special occasion merited a cream cake–either black forest or pineapple-and-cream (sort of like black forest without the chocolate and cherries)– which, unless you were rich and could afford a custom cake, always came from the freezer of the local bakery.

Though cakes were becoming popular, baking had yet to go mainstream. Ovens–at least in my middle-class environment–were used more often for storage than for cooking. As a child, I remember going to a relative’s house and watching her open the oven, only to pull out books. People still use ovens to store extra frying pans and griddles, which they haul out on the infrequent occasion that calls for baking or roasting. Qasim recalls that women would come to the bakery to take baking lessons from his father.

In the 2000s, the rise of private television networks and cooking shows helped spur home baking, Qasim says. More women learned how to bake, and there are now a plethora of bakers selling everything from customized cupcakes to pastries on Facebook. Gourmet, a bakery chain in Lahore, has transformed over the years into a food conglomerate that sells its own brand of bottled water and even runs a news channel called GNN, whose logo consists of the stylized G from the bakery’s insignia followed by the ‘NN’ of CNN. It’s the perfect parallel to urban Pakistan: part local, part lifted from the west, fused into something that feels like it could be your own take.

People are just going nuts over the decoration.

But Qasim laments that people who knew the true value of a cake have long since left Lahore–or this world. “Now you can make whatever. ‘This is a cake,’” Qasim said, mocking his own rudimentary sales pitch. “‘Okay, give us this.’ They don’t even look at it. It’s just cake on the bottom; put almonds on top, put chocolate. I order in cakes from everywhere [to sample them]. There’s no taste. People are just going nuts over the decoration.”

His lament is for a different age and the crappy cakes he has to sell in these undiscerning times. Mine isn’t about other crappy cakes: it’s but this one.

At the Kitchen Cuisine bakery, the black forest comes in two versions: a ‘French Black Forest,’ made with custard cream, and the ordinary version. According to Mohammad Usman, the salesperson at the counter on the day I visit, people these days generally don’t like cream cakes. But isn’t the black forest cake mostly cream? I ask.

“Yes, but the taste is different,” Usman says. “The sponge is chocolate,” his co-worker Gulzar Ahmed points out, somewhat inexplicably.

How can people simultaneously dislike cream and be loyal to a cake that is mostly cream?

“People buy it as a sweet dish,” explains another man, also named Mohammad Usman, using the common parlance for dessert, as he sits at the counter of Yasin Bakers in Lahore’s Taxali Gate neighborhood. “Kids don’t like it as much.” A bakery helper, mistaking my interest in the black forest cake as an order, starts to box it up. When Usman sees me taking a photo, he admonishes me to not handle the cake myself lest I mess up the icing.

To make my way to Taxali Gate, I’d boarded the women’s section of a local bus and maneuvered my way through the crush of people to find a space to stand, jealous of the enterprising students who’ve found some valuable real estate near a window. There are middle-aged women in crumpled clothes, long dupattas (or scarves) draped over their heads. One woman who managed to find a space to sit is voluntarily holding another woman’s baby. The bus passes through the neighborhood where I spent the ninth year of my life–1994, the year I learned to speak Urdu fluently and fly a kite–a year that firmly joins me to this city, to a small brick house, to a history shared by my family.

At some point, no matter how my tastes have changed or my accent or life is different, I can’t leave the black forest cake, an indelible part of middle-class life, behind. The appearance of a black forest cake on your birthday, your name in icing framed by a circle of cherries, showed that your parents were making a big deal of your special day. When visitors brought it to your house, it signaled that they’d spent money.

As you get older, wiser–perhaps even make a better living than your parents–the black forest cake starts to feel passe. It is the cake you poke fun at, that you associate with your middle-class roots, a throwback to your former life, to a time that you sometimes think was simpler, easier, even happier, though in all likelihood you were just young. You leave your neighborhood. You move somewhere else, to a newer part of a city, to a bigger house, where the neighborhood bakery sells more than just black forest cake. Your accent changes. You learn self-loathing, and it extends to the cake, with its Pakistani pineapples and peaches. Yet there the cake remains, in the display case of the patisserie at the upscale supermarket, on the Instagram stories of a friend who doesn’t even live in Pakistan anymore.

Related Reads

Even after you upgrade your vocabulary from ‘sweet dish’ to ‘dessert,’ you will one day find yourself in a bakery asking the salesperson to box up a black forest cake. You’re going to visit a relative, and you need to take something along. Bringing a cake to someone’s house in Pakistan is like going to a dinner party with a decent bottle of wine: the correct thing to do. You look around at the unfamiliar cakes and flavor pairings and even though you know the black forest cake isn’t great, it can’t possibly be all that bad. Then someone returns the favor, bringing a cake to your house, a cake that no one can finish, in a box that takes up too much space in the fridge. And so the black forest cake keeps boomeranging its way into your life.

Of course, there are more choices now. At Fazal Bakers, a bakery in Lahore’s Mochi Gate neighborhood, a chocolate chip cake is a more popular dessert, and fewer people request names in icing on black forest cakes. We have choices now.

I’ve moved on from the neighborhood bakery. I can buy whatever fancy dessert is doing the rounds on Instagram. I can order a cake from the home bakers proliferating on Facebook, or order in from an upmarket cafe. I know better.

On a long-haul Lufthansa flight last year, as I stress-ate my way through the flight menu and drank copiously, I had my first (and, to date, only) encounter with a German Black Forest Cake, its layers of cream and chocolate flakes conspicuously similar to the cakes I’d grown up with in Pakistan. I thought about my hang-ups about the cake. Could I willingly eat this? What would people say?

But what the hell, I thought. I ate the whole thing, cream and sponge and all.

It was delicious.