Survivors recount a terrifying run from extremists after a university is attacked.

Part II: Flight Response

Boko Haram has staged hundreds of shooting rampages and suicide bombings at schools across northeastern Nigeria. The stories in this three-part series are those of the survivors.

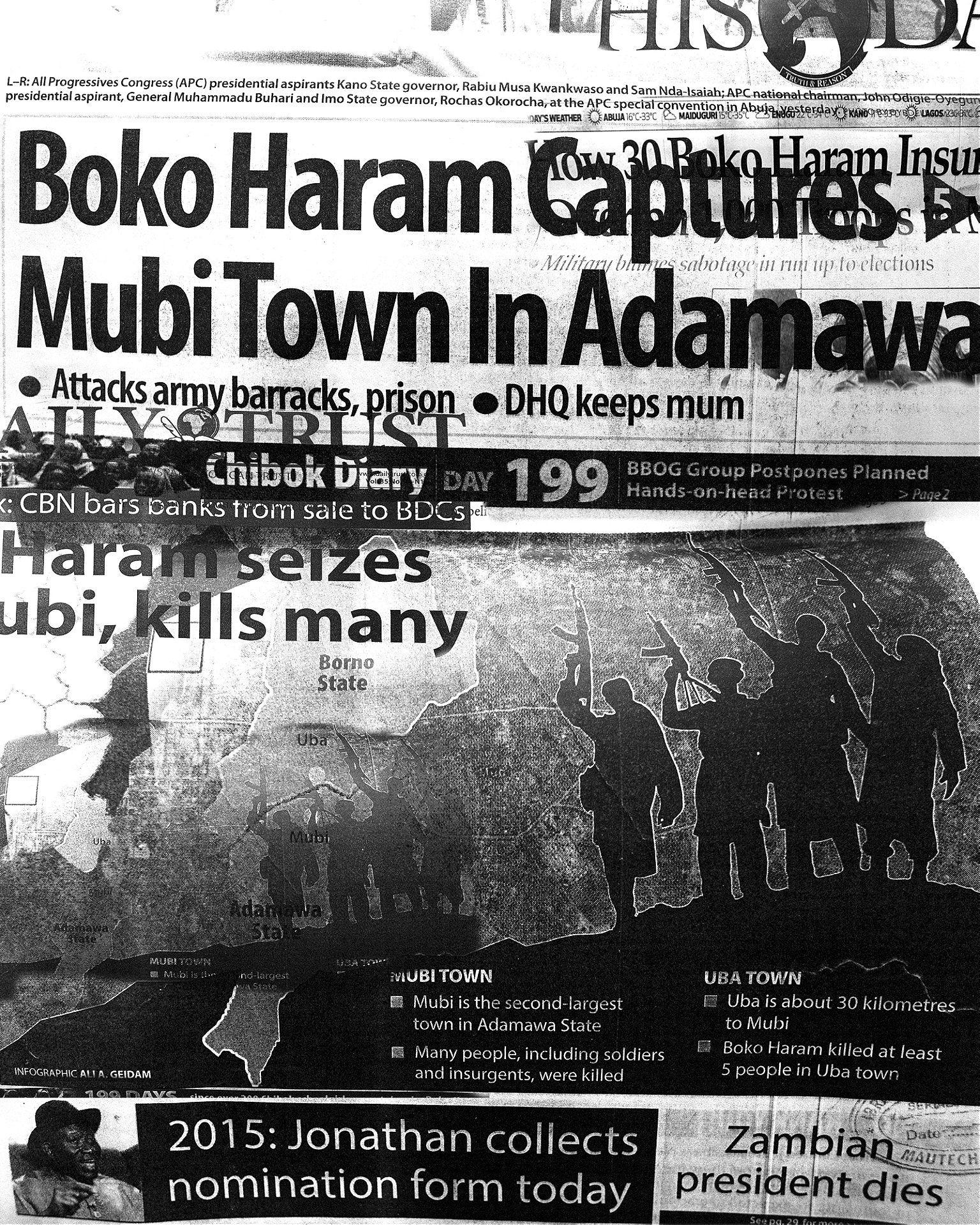

The exodus began with a rumor. It was Oct. 29, 2014. Glory Ibeh, then a 24-year-old political science student at Adamawa State University in the small Nigerian city of Mubi, was standing with classmates outside a lecture hall waiting for a professor to arrive for the first class of the day. Suddenly, their conversation turned buzzy and anxious. Someone had told someone and so on until word reached the group: Boko Haram was on a rampage in town.

The students had lived with the insurgency for several years. They had attended lectures, socialized, and planned for the future while a terrorist group grew in size and voracity around Mubi. Boko Haram had captured towns and villages that tourist brochures might have described as a stone’s throw away from the university.

Students started trickling back to their dorms. By 9:30 a.m., the rumor was confirmed: Ibeh could hear explosions outside. She knew it was time to leave.

Girls turned their bunks into disarray as they gathered whatever belongings they could. Some managed to stuff their academic certificates and transcripts into small bags, chosen so that they could run fast if necessary. Higher education is a privilege and an honor for Nigerian students; many overcome corruption, family strife, and other obstacles to get to university. Documents attesting to their success are often literally irreplaceable; an aging, corrupt system means that original documents are often necessary evidence of educational achievement.

Frantic phone calls were made to friends and family as students looked for ways out of town and rides to Yola, the state capital. Ibeh squeezed into the back seat of a crowded car. Twenty minutes into the journey, the car broke down. She got out and walked 20 miles east, across the Cameroonian border. Local Fulani herdsmen had been making the same journey for hundreds of years, allowing their cattle to graze on the vast savannah that crosses national lines.

Alongside other refugees, Ibeh waited. “Cameroon was just the beginning of our suffering,” she tells me.

Adamawa State University was inaugurated with great pride in 2002, one of three colleges founded by the government in Mubi. The city of about 130,000 people was known for its bustling cattle market. Dorm-loads of students pursuing higher degrees and buying products other than livestock infused Mubi with a renewed sense of purpose and power.

On the evening of Oct. 28, 2014, the university’s vice chancellor, Moses Zaruwa, was at home with his family when he received a phone call. Tall and lean with a mustache, the 45-year-old administrator was told that the Nigerian military was retreating from a base about 35 minutes from Mubi, which served as a vital buffer against Boko Haram. At 6:15 a.m., after a restless night, Zaruwa got another call from a security contact who told him in no uncertain terms to get out of town. It took him a few seconds to digest the gravity of the situation: He and everyone he knew, including his family and the students that Mubi so proudly hosted, were defenseless.

Zaruwa began calling his colleagues one by one and telling them to alert students.

The university did not have a digital or telephonic way of warning everyone simultaneously. The vice chancellor rushed to a boy’s dormitory to tell the residents they had to leave. School buses were available to evacuate students, but it was too risky to drive on the roads. Everyone had to find his or her own way out of Mubi. Zaruwa drove a Jeep through the bush to get to Yola, bypassing roads where Boko Haram might be.

Winnie Gwalasha in her room at Adamawa State University.

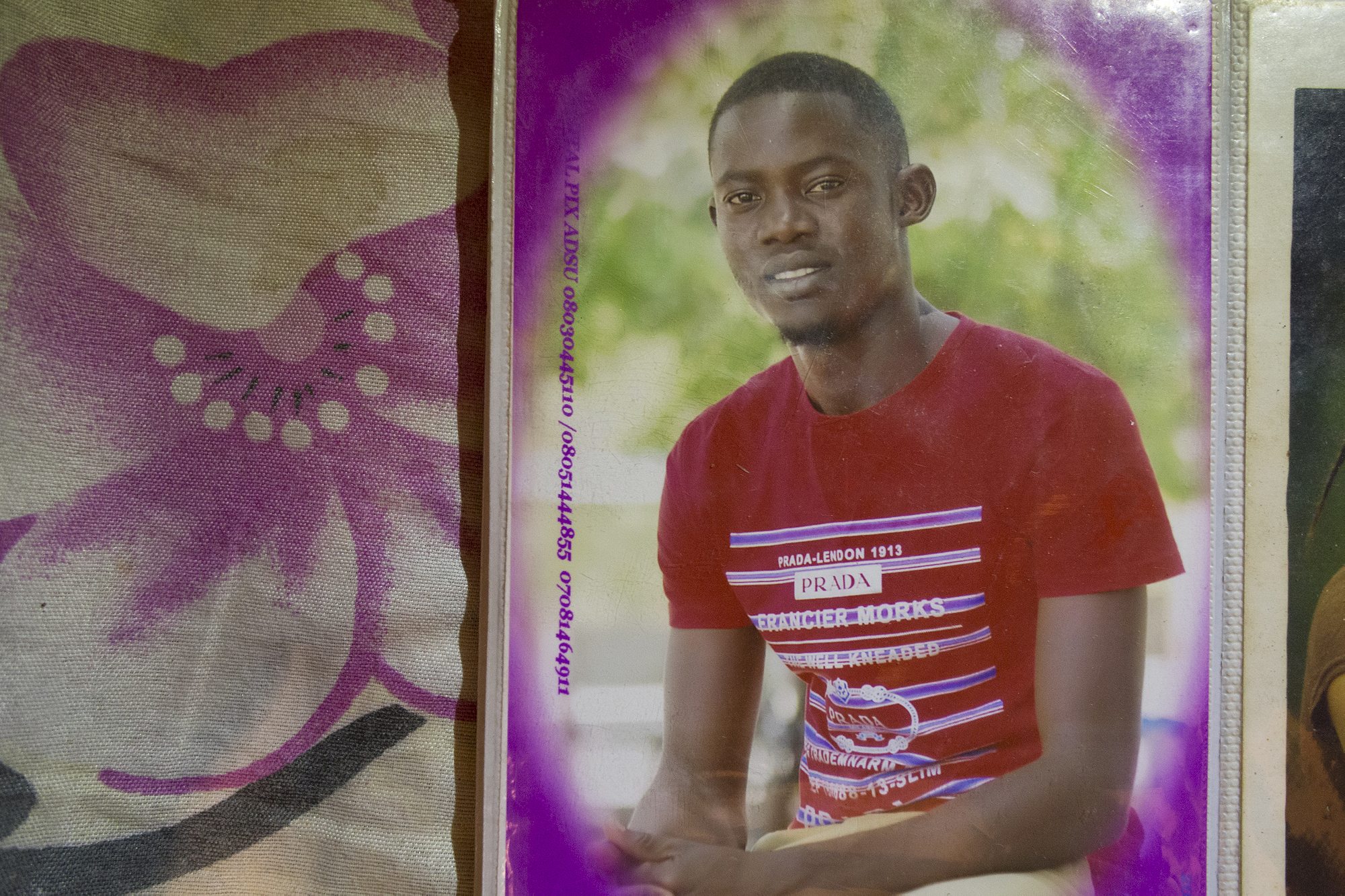

Winnie Gwalasha, a political science student in her early 30s, initially decided to stay behind. She didn’t want to leave her younger brother, Labaga, who lived off campus. “Labros mummy’s boy” was the pet name she and his sisters had given him, the only boy born amid a string of girls.

Gwalasha called Labaga, who was just a few weeks shy of turning 28. She could barely hear his voice because he spoke in whispers. He was trapped in a bedroom with several people, afraid to leave because they could hear the gunmen outside. The siblings hung up.

When Gwalasha thought she heard military planes overhead, she feared an aerial bombardment of Mubi to counter the terrorists. She decided to leave without Labaga, walking several miles to a village, where she found a place in a car going to Yola.

Once she arrived at her family home, she dialed her brother’s number again. It was unreachable.

Glory Ibeh sat in a grassy field in Cameroon that was packed with displaced people, many of them from Mubi. “Three days passed and immigration officials only gave us water,” she says. “They would call us for assemblies, bully and insult us…. We were just helpless.”

After three days, Ibeh managed to jump into a truck that was headed back to Nigeria. She paid the driver 3,000 Naira ($20), the only cash she had. The truck weaved through bushes and valleys, with the dark silhouette of the Mandara Mountains demarcating the edge of Ibeh’s home country. It took her a week to get back to her family’s house in Yola.

Bad news awaited: Christopher, her brother and a fellow student, was still missing.

Christopher, 27, was studying economics when Boko Haram attacked Adamawa State University. He and seven other young men raced toward Yola on two crowded motorbikes. On the way, they nearly drove into masked gunmen who had blocked the road.

The Boko Haram militants began shooting at the bikes, forcing the young men to stop. Christopher and the others were made to kneel in the dirt and, strangely, offered dried dates. Three men refused to eat the dates and were shot on the spot. A fourth was beaten and cut across the neck. Just as Christopher and another companion were being offered dates, they heard the sound of a Nigerian military aircraft overhead. The gunmen panicked, and in the confusion, Christopher and his friend escaped.

She screamed with shock when she heard his voice

After several days of walking, they arrived in a town. Christopher was able to call his sister. She screamed with shock when she heard his voice. He had been gone for two weeks. She had assumed he was dead.

Janet John, 24, looked half dead when she stumbled up to her aunt’s house in Yola four days after the attack in Mubi. Her hair was wild, her feet swollen and bleeding. John’s fatigued body had to be carried inside.

When the militants came to campus, John and some other students had fled into the wilderness for refuge. On her smart phone are photos of confused-looking classmates drawing water from muddy streams and hiking through the mountainous terrain of northern Adamawa State. “We started trekking, not knowing where we were going, but we were just moving,” Janet recalls. It was harvest time, just after the rainy season, so they scavenged groundnuts and sugarcane in abandoned farmlands.

The prospect of death, though, never scared her. “All I was thinking about was school,” John says. “I did not have my certificate. I did not have my transcript. How would I start again?”

After the attack, the university shut down. There was a real fear in Mubi that the students would never come back. Shops would be left with a glut of mattresses, school supplies, and clothing intended for young people. Boko Haram’s sting would linger.

Nine months later, though, Adamawa State University reopened. Moses Zaruwa was one of the first people to return. Classrooms and dorms had been ransacked. The university chapel and administrative building were burned and vandalized. A report published by the Adamawa State Ministry of Higher Education, assessing “the damage caused by the insurgency,” estimated the cost of the attack at 540 million Naira ($1.7 million). On the list of needed repairs were broken windows, damaged portraits of past administrators, and missing laptops.

When I meet with him in the Brutalist-style building where university administrators work, Zaruwa is dressed casually in a white caftan patterned with small black diamonds. A pen is clipped to a breast pocket. The school’s lecture halls are filled to the brim; the administration says 90 percent of students have returned. Yet the campus remains on edge.

“Some students, on the spark of a rumor that Boko Haram is coming, will leave town,” Zaruwa tells me. “I don’t blame them. I feel sorry for them.” He has recruited local hunters and men with combat experience to guard the gates, allaying fears as much as possible.

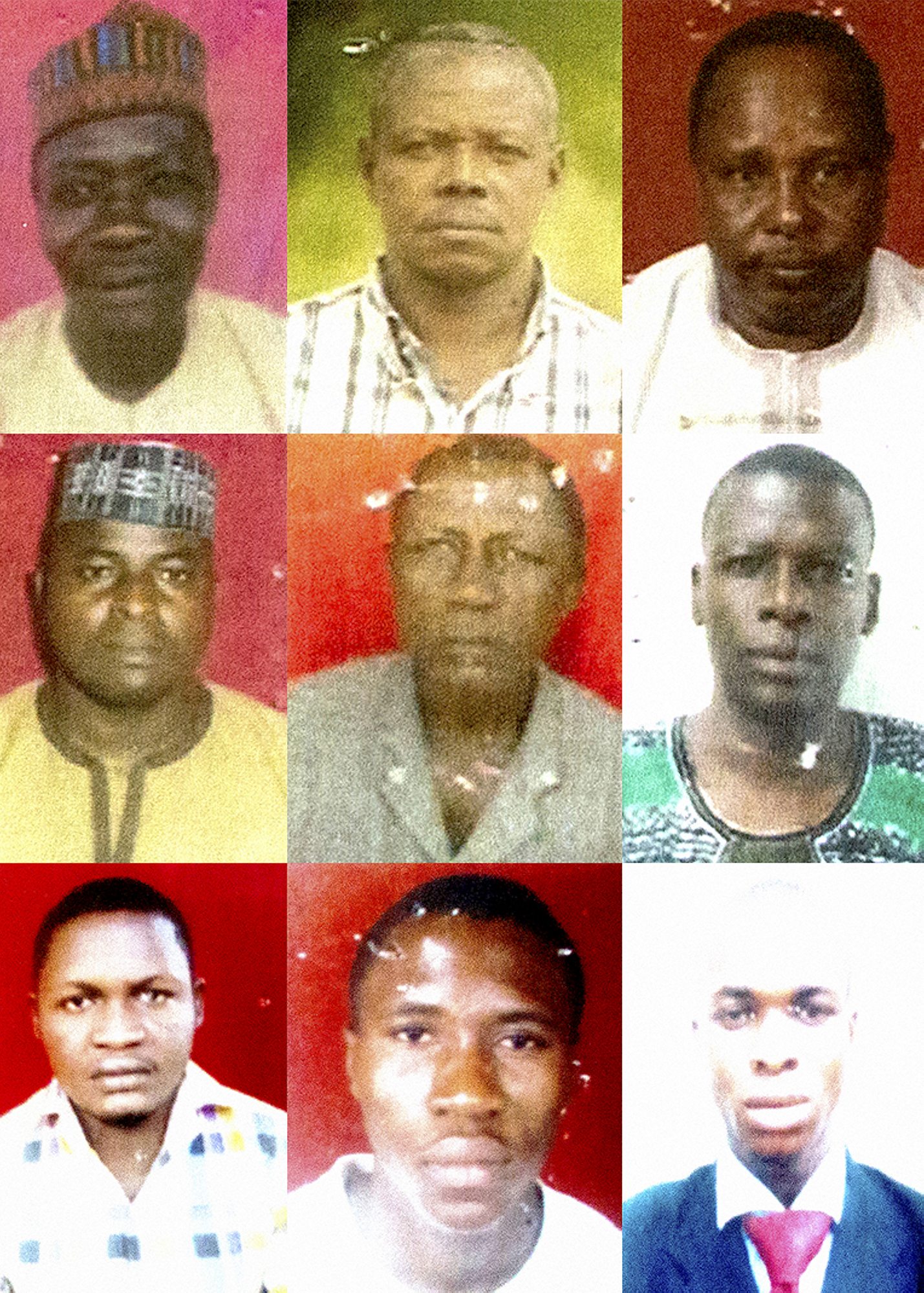

Glory and Christopher Ibeh came back to campus; Janet John did, too. Winnie Gwalasha joined them—but Labaga didn’t. No one ever heard from him after that violent day in October 2014. On the fourth page of the school’s damage report, in a table titled, “Estimated compensation for lives lost in the university,” his name is misspelled as “Labaya.” The value of his life is estimated at 2.5 million Naira (about $8,000).

“My life is not sweet anymore,” Gwalasha tells me with tears in her eyes. “Labaga was the only one who would come to campus to check on me.”

Over the months since returning to campus, students have loosened up slowly. The university once banned most social events to avoid attracting violence. When I visit, a colorful poster catches my eye. It is promoting a variety night and student social.

At the event, a lecture hall has been turned into a makeshift nightclub. Red and blue lights pulse on and off, reflecting on the worn black leather seats at students’ desks. Nigerian pop tunes emit from the sound system. The energy in the packed hall is electric, as students cheer for their peers who sing, rap, and dance.

Vandi Maikyau, 24, is a political science student supervising the event. Sunglasses balance on his fresh haircut, left longer at the back like a mullet. Around his neck is a wooden necklace shaped like the African continent. After the 2014 attack, Maikyau thought about enrolling somewhere else or pursuing a pipedream of becoming a hip-hop artist. Instead, he came back to finish his degree. He helped organize the variety night to signal that, for the first time in years, it is possible to feel that campus life might be something close to normal.

“Prior to the insurgency, there were events every week,” Maikyau says. “It has been a long time since students have experienced a night like this.” His eyes are bright, and his lips curve into a smile.

Reporting for this article was supported by a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation through the Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Go back to Part I: We Will Not Stop Coming or continue to Part III: Folktales and Nightmares