Portland’s Ota Tofu Company is intertwined with a dark American legacy.

PORTLAND, Oregon—

In the prehistoric days before everyone got all orthorexic, soy and gluten were staple proteins for vegetarians. During my own decade-long foray into vegetarianism, I was thankful for the wide variety of meat analogs, a good century in the making (thanks, Seventh Day Adventists!), but my biggest revelation was learning to cook with tofu. It could be mashed into pancake batter, scrambled with vegetables and twisted into tortillas, and of course, tossed into a stir fry.

Back then, I knew that my town, Portland, was the birthplace of the Gardenburger, but I had no idea that I’d also grown up in the same city as the longest-standing tofu shop in the United States. I hadn’t realized that local hippie ready-to-eat food companies like Higher Taste and King Harvest had been using this venerable tofu in their respective Golden Slice sandwich and Grinning “Chicken” Tofu Curry (the now-defunct pita pocket satisfyingly overflowed with savory cubes of curried tofu, topped with shredded carrots and a solitary black olive).

For Ota Tofu Company, the process of making tofu hasn’t changed significantly in more than a century. The beans are rinsed and ground to pulp before cooking and flushing the soy milk from the slurry through a cloth bag. Today, the nigari salt is purchased from a supply company instead of made from evaporated sea water, but it still turns creamy soy milk into chubby curds. Instead of cobblestones set upon planks, stainless steel hydraulics gently press the water from the tofu; the process still converts the loose coagulum into cottony, semi-solid bricks, and these delicate bricks are still carefully cut and packaged by hand.

Standing at about 5’2”, Eileen Ota is strictly business, wearing an apron and white rubber boots, a kerchief to hold back her bobbed, salt-speckled hair, and wire-framed glasses perched on her nose. The phone rings off the hook. A Vietnamese restaurateur comes in, wheels his hand truck past me, and another worker loads it with buckets of tofu. I try to stay out of the way.

Ota hands me a paper hair net and tells me that I need to ask permission before photographing anyone. I put it on and with my nicest manners, head into the tofu shop’s work space.

Back in the tiny, fluorescent-lit factory, the women massaging the curds into the cheesecloth-lined boxes are shyly smiling and ducking my camera, but reluctantly allow me to include their gloved hands in a few shots. Ota’s elderly husband, Ko, allows me to snap a few from behind his station at the soy bean cooker.

I’m taken with the efficiency of the small operation. Everyone has a job to do and they do it well. After more than a century, the kinks have been ironed out. The machines in the factory can crank out 500 pounds of tofu an hour, but much of the work still requires the touch of human hands.

Between 1890 and 1910, Portland’s Japanese population grew from just 20 to nearly 1,500 people. In addition to Nihonmachi (Japantown) just north of the city’s urban center, a second, suburban community emerged in the Montavilla area of East Portland. At first they were mostly men, settling in the fertile foothills of Mount Tabor to farm berries and vegetables. Later women began to arrive to the city, taking out ads in the local paper seeking domestic work in private family residences. In 1905, the local Y.W.C.A. began offering Saturday evening cooking classes to Japanese women, giving inexperienced Nikkei a leg up in American cookery.

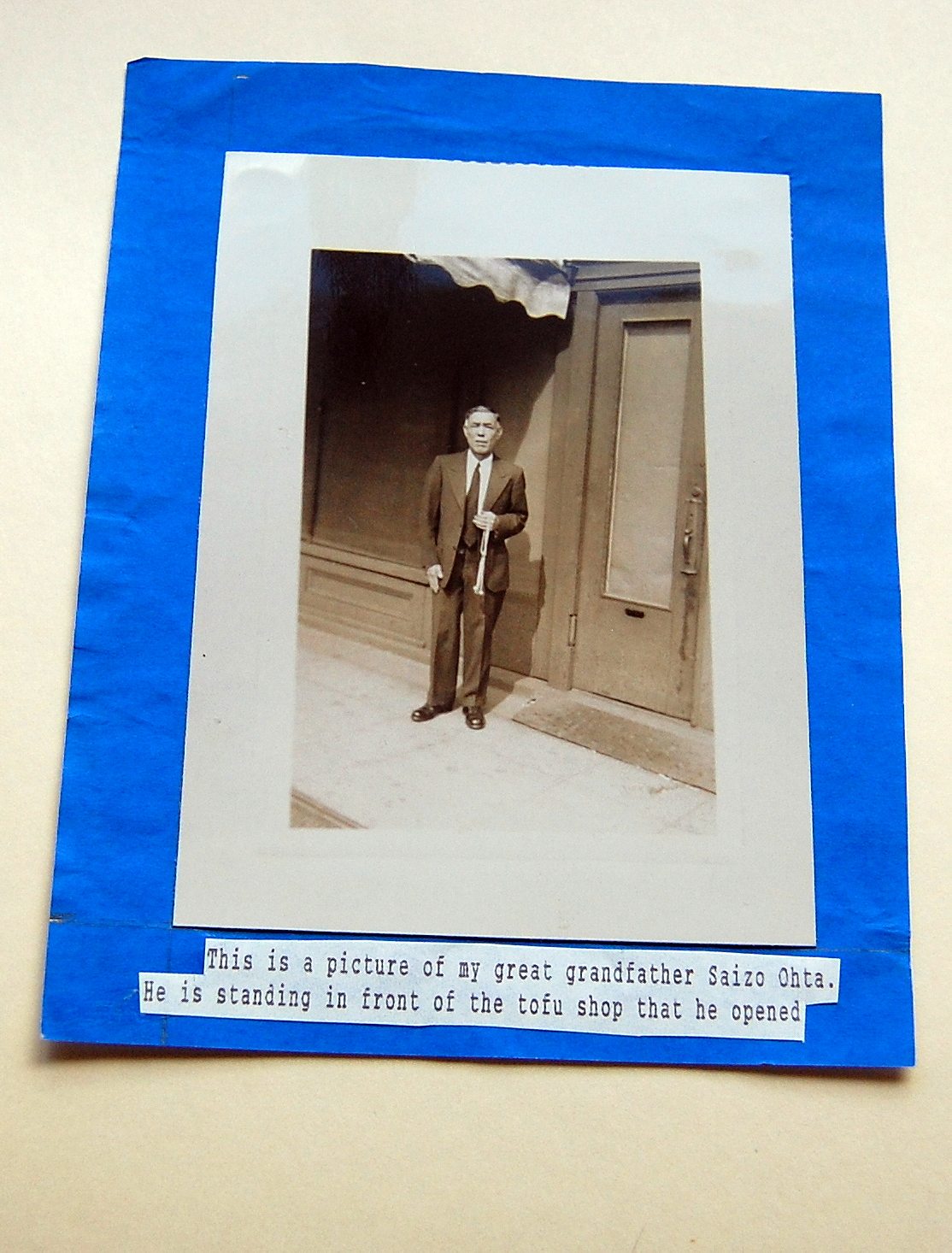

With a more gender-balanced population in the mid-oughts, people married and started families, and Nihonmachi went from a seedy district of drifting laborers (and the caterers to men’s vice) to a blossoming neighborhood. Sukiyaki hot pot restaurants (a Japanese analog to the then trendy chow mein parlors run by Chinese cooks), bath houses, grocery stores, and a fish market opened in service to the growing Japanese community, and Saizō Ohta (the original Anglicized spelling of the family’s name) arrived from Okayama with his two older brothers.

Much mystery surrounds the origins of the company. One of the elder Ohta brothers opened the tofu shop in partnership with a Mr. Nagaro in 1911, whose given name and place of origin is unknown. It’s not even clear if the Ohtas had been tofu makers back in Okayama, or if they’d merely seized an opportunity to fill a need in their new city. The brother (whose first name is also not known) then returned to Japan, leaving his half of the business to Saizō. Originally called Asahi Tofu, the tofu-ten, as a tofu shop is known in Japan, was first located on NW Third and Davis, sharing an address with a Japanese laundry. When Saizo and his wife, Shina, took over the business, they moved it around the corner to a new location, and the name of the business was changed from Asahi (meaning “morning sun”) to the family name. No one knows what happened to mysterious Mr. Nagaro.

While Sukiyaki was slowly gaining popularity throughout the U.S., Japanese cuisine was still largely misunderstood and unappreciated. Portland directories in the 1920s and 30s listed the tofu shop as a bakery, the “soy bean cakes” evidently having been confused for pastry by the directory’s publishers. However, one gushing restaurant review published in The Oregonian in 1932 got it right, noting that the Tokio Sukiyaki House, located a block away from the Ohtas’ shop, included ingredients such as bamboo shoots and celery sprouts imported from faraway lands, “while the soy bean cake is made locally.”

Although their Chinese neighbors had always formed a good portion of the Ohtas’ customer base, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 brought growing tensions between the Chinese and Japanese communities to a head. Japanese business owners tried to keep their heads down, but Chinese customers stopped coming in. From their tiny shop, the Ohtas carried on, making silky tofu, puffy and golden-fried aburaage, and gelatinous, bruise-hued blocks of voodoo lily paste called konnyaku. Then, Pearl Harbor changed everything.

Anti-Asian racism wasn’t new, but Pearl Harbor was the shit that hit the national fan. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, allowing people with Japanese, German, or Italian ancestry to be incarcerated in concentration camps. Those with Japanese ancestry—nearly 70,000 American citizens—were forcibly evacuated to the assembly center (located at a decommissioned cattle stockyard) for detention before being shipped off to an Idaho concentration camp called the Minidoka Relocation Center. With only 48 hours’ notice in some cases, Japanese businesses were liquidated and property sold off for whatever amount they could get. Whatever property hadn’t been sold was confiscated. Nihonmachi slowly converted to Portland’s second Chinatown as Chinese residents and business owners took advantage of the newly vacated properties, but there were no longer any tofu makers in town.

Life in Minidoka was demoralizing, with families forced into barracks within barbed wire enclosures, living in cubicles divided by a thin sheet. They were fed army rations that attempted to erase their Japanese identities, supplemented with hot dogs and SPAM. If they were cooperative and proved their loyalty, adults and teens might earn the privilege of working in potato and sugar beet fields to break up the monotony of their daily lives. Nonetheless, people carried on, trying to make the most of things by writing newspapers, creating schools for their children, and growing gardens.

On Jan. 2, 1945, the War Department declared that the Japanese at last were free to leave the camps, but about a third of Japanese-American Oregonians never returned to their former hometowns. Of those that did return to the state, most tried to return to farming, but were met with racist resentment.

Saizō Ohta died at Minidoka in 1943, leaving Shina to take over the shop and run it herself after the war ended. Mercifully, the building’s landlord had been sympathetic during the war and had saved the tofu equipment and the shop space (where the Ohtas also lived), and Shina reopened the shop as Soybean Cake Company. Though Japantown had been transformed into New Chinatown, there was still a customer base in the neighborhood who bought tofu.

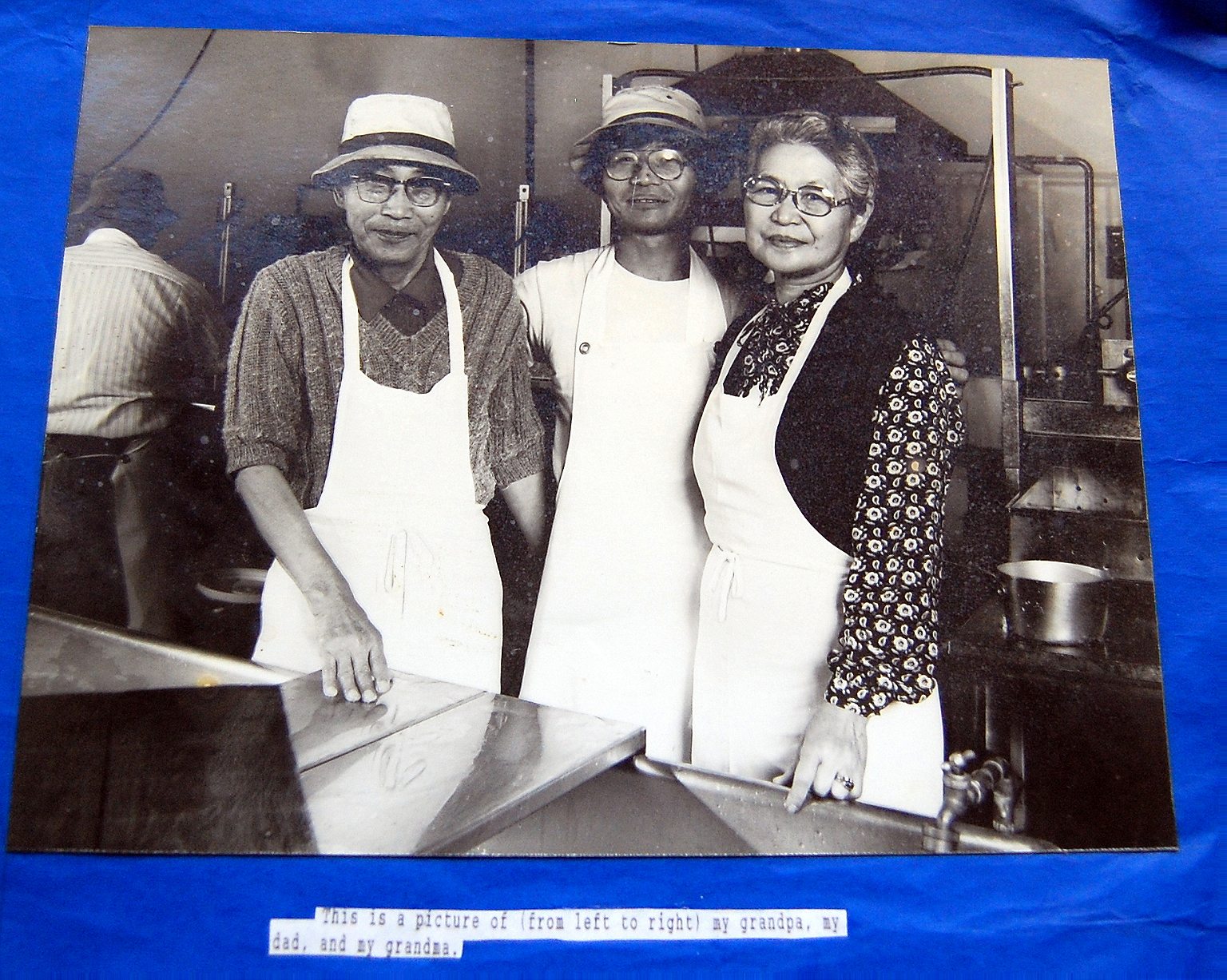

Saizō and Shina’s daughter, Matsuno, had been in Japan receiving her education for several years when the war broke out, and she stayed put until well after the war ended. She returned to Portland in 1955 with her husband and their three children (during which time the spelling of their name was updated to Ota). Two years later, Shina suffered a stroke, leaving the care of the shop to her son-in-law and her grandson, Koichi (usually called Ko).

Over time, things began to settle back down somewhat for Portland’s Nikkei. Japanese grocery stores like Anzen reopened soon after the war, and restaurants like Bush Garden slowly resurfaced. By 1970, a community cookbook produced by the ladies of my great-aunt Ruby’s (mostly white) church included a few recipes provided by Harriet Uchiyama, a Chinese-American whose Japanese husband had spent a chunk of his childhood at Minidoka. Her recipe for “roast chicken,” while benignly named, is teriyaki in disguise, flavored with hoisin and soy sauce (a marriage of Chinese and Japanese flavors), brown sugar, honey, and garlic. Japanese food was finally coming out of hiding.

In the 1970s, anti-Japanese sentiments faded as Americans became enrapt with health foods. Like granola and sprouts, tofu was on trend. Now it wasn’t just Japanese restaurants and markets that bought the Otas’ wares. Health food stores, hippie co-ops, and vegetarian-friendly cafes (like King Harvest) were popping up all over town. Even mainstream stores like Safeway began carrying tofu on their shelves.

It was about this time that Ko, then owner-operator of the shop, married Eileen (a Japanese-American Portland native), and a few years later they moved the shop across the river to their current location on SE 8th and Stark, with a few modernizations in place. Though he has slowed down somewhat, Ko still works the soybean grinder and cooker.

Over the past few years, a couple of Vietnamese tofu shops have opened in Portland, selling firmer tofu with different flavors. In Japan, the method of making nigari-style tofu like Ota’s has largely fallen out of fashion, mostly relegated to mom-and-pop tofu-ten in neighborhoods and Japan’s countryside, but its flavor is considered the finest, with a subtle sweetness coming through. Tofu this good can be eaten plain, or drizzled simply with soy sauce and a sprinkle of sliced scallions.

Though she is a font of patience and kindness, Eileen and I lamented the youthful rejection of labor-intensive traditional foods. Younger generations prefer convenience, and are less interested in outdated techniques, both in America and Japan. It’s the older immigrants who’ve been settled here for decades that prefer traditional ways and foods, whereas today’s immigrants bring their modernity with them.

As Ota’s new Korean, Chinese, and Vietnamese customers acclimate to American foodways, they tend to come in less frequently. But for immigrants, language and food are like time capsules; by maintaining traditional recipes and techniques as the city rapidly changes around them, Ota Tofu honors this. For white Portland natives like me, Ota keeps me linked to my city’s history.

Anzen was Ota Tofu’s longest-standing customer until they closed in 2014 (after 109 years in business). Today, a distributor in eastern Washington is the shop’s longest-standing account—around since Ko’s parents’ day—thanks to Andy’s Market in College Place, catering to the students at Seventh Day Adventist-affiliated Walla Walla University. Most of their business comes from wholesale accounts held by local restaurants and stores, but they still graciously sell their tofu to people like me, regular folks who wander in off the street with a few bucks in their pocket. If you bring a bucket, the pressed-out soybean meal called okara is free (it’s great mixed with ground pork and fried into patties or meatballs, to eat with ramen). Ota Tofu Company does this as a service to the community. Anyone who has tasted tofu made only hours ago knows what a service this is.