Although the Nigerian government claims to be winning the war on Boko Haram, schools are still under attack.

Part III: Spirits in the Trees

Boko Haram has staged hundreds of shooting rampages and suicide bombings at schools across northeastern Nigeria. The stories in this three-part series are those of the survivors.

In the mid-1940s, my widowed Fulani grandmother raised my father and his four siblings in a small bungalow in Yola, the capital of Nigeria’s northeastern Adamawa State. Fifty years later, I spent slow summers there riding beat-up bikes in our family compound.

Yola rarely made the news then. The town was a constellation of half-completed structures, ever on the verge of urbanization, but never quite making the full shift. Cattle like the ones my grandfather herded before he died strolled sedately across unfinished roads. On harmattan evenings, if I stood on high ground, I could see untouched savannah grasses, blowing in the wind and rolling outward behind the clusters of corrugated roofs that ended where the town did. I remember electricity blackouts that signaled story time before bed, a chance to huddle wide-eyed around flashlights to hear stories of spirits that stole human souls and lived in gnarled trees.

It is such a tree that Bashir Bazza looks at warily one blindingly hot October afternoon in 2015. We are standing on the grounds of the mosque on his university’s campus in Yola. Around an ancient baobab are black stains—dried blood from a suicide blast by a Boko Haram acolyte that killed an estimated 16 Adamawa State Polytechnic students just one week ago.

The grotesque trunk and twisted branches reach skyward, like totems to the spirit world. I feel as though the tree has been uprooted from my memories of Hausa folk tales and replanted in Bashir’s waking nightmare.

On Oct. 23, a few hundred young men had gathered to worship in the mosque’s courtyard. “When we stood up to pray, we heard the sound,” Bazza says. “Then we saw people lying down, falling down, people’s legs, blood everywhere.”

He identified some of his classmates among the mangled. He had arrived late for prayer that day, so he was at the periphery of the blast, detonated by a suicide bomber near the baobab tree. Bazza was not seriously injured. In the days that followed, though, he developed a sore throat—a side effect of inhaling the bomb smoke that hung thick and black in the air, mixed with a fine spray of blood. His hearing had also been dulled by the blast.

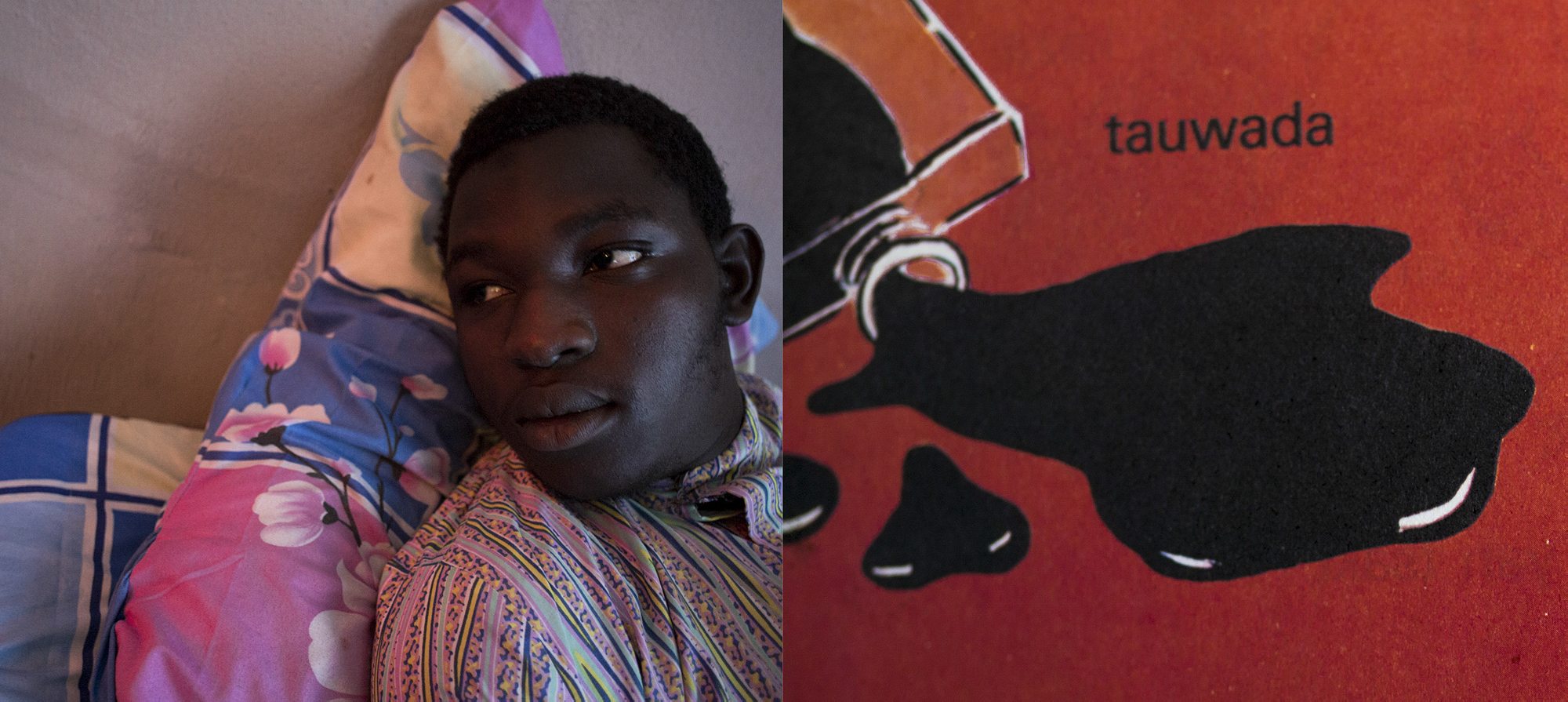

There are other wounds that I cannot find the right words to describe. Even “trauma” somehow feels too clinical. Bazza gives the impression of someone in purgatory, wandering in a limbo state that bonds many young people across northeastern Nigeria. Churned up and displaced by Boko Haram, they have survived. They are not listed among casualty figures. But they are victims all the same.

Hamza, 17, whose name has been changed at his request, is another one of these victims. He’s an athletic boy with skin darker than its natural tone from all the time he spends outside. In February 2014, he was a 13-year-old student at the Federal Government College (FGC) in the town of Buni Yadi. He had just returned from the winter holiday and was getting back into the reassuring routine of school life. On the night of Feb. 25, he remembered that he needed to wash his uniform for classes the next day. While soaking the green-and-white clothing in soapy water, he heard shouting outside. Probably just classmates returning from a visit to town, he reasoned.

The voices became louder. Hamza heard gun shots—then, Allahu akbar! It wasn’t a call to prayer. It was a war cry.

“They started shooting and piling up bodies,” Hamza remembers of Boko Haram’s assault on the school. “When they saw you were not dead, they shot you.”

He and a friend ran to hide in a bushy area outside to wait out the massacre, which lasted for several hours. Then the guns went silent; the militants had left. At first light, Hamza and his friend went back to see if there were any boys who needed help.

Dead bodies sprawled on the pathways he had walked to class. One boy who was bleeding from the neck called to him and begged Hamza to find his younger brother. “We went apartment by apartment until we found his dead brother’s body. We carried his brother’s body to him,” Hamza says. “When we showed him his brother, it wasn’t even up to five minutes, and he too died.”

It was reported that 59 boys were killed. Hamza puts the figure closer to 100. He personally lost a dozen friends. FGC Buni Yadi had female students, but none were killed. Mausi Segun, a researcher for Human Rights Watch (HRW), describes this as part of a pattern in which male students die and girls get more lenient treatment—at least at first. “[Girls] were intimidated to stop attending school,” she explains. “If they didn’t stop, they were targeted for abduction.”

If students heard what they thought was gunfire, they would scream and run

Three weeks after the attack, Hamza was with his family when the local Ministry of Education announced that all FGC Buni Yadi students would be transferred to FGC Maiduguri. Even when Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State, closed most schools later that year, this one would remain open. Some of its grounds were used as a displaced-persons camp.

The new city never felt safe to Hamza. The constant attacks by Boko Haram made him and other students jittery. “We couldn’t learn anything because of the noise,” he says. If students heard what they thought was gunfire, they would scream and run out of buildings.

To make matters worse, FGC Maiduguri was overcrowded. Other students had been transferred from towns such as Bama and Chibok, the sites of other Boko Haram attacks. “Children would cry out that they didn’t get any food because there were so many of us,” Hamza recalls.

While home for a holiday, Hamza decided not to go back. The two-hour journey from Maiduguri to his parents’ house was lined with desolate fueling stations, empty villages, burned buildings, and military checkpoints. Boko Haram had been known to stop travelers, kill them, and leave their bodies on the side of the road. Spent by the terrifying trip home, Hamza asked his father if he could enroll in a local Islamic theological college. Later, he would enlist in the Nigerian military. His father agreed.

“When I close my eyes and think about the situation, I could cry,” Hamza, who is now 17, tells me of his time in Maiduguri. “Sometimes, I would look at my friend and get this feeling that it could be the last time I would see him, because if the insurgents burst in, I didn’t know where he would go and I would go.”

This January, a suicide attack at the University of Maiduguri killed at least four people and injured another dozen, maybe more. Though the Nigerian government insists it is winning the war against Boko Haram, questions remain about the safety of students who are returning to school in northeastern Nigeria.

“If urgent steps are not taken to ensure that they have the right to education,” Segun of HRW explains, “this could mean that these children are locked in unending cycles of underachievement and poverty.” Those steps include getting as many displaced kids as possible into school with minimal cost to their parents, developing early-warning systems for future attacks, incentivizing teachers to return to classrooms, and building more schools in safer areas to accommodate the students who have nowhere to go. Segun says that the state also must stop using schools for military purposes and instead make them safer for students and teachers.

The task of helping young people like Bazza and Hamza cope with all that they’ve seen and lost is more complicated, but no less important. Without support, their emotional limbo could become a permanent condition.

Bazza tells me that he tries to forget what happened whenever he can, at least for a little while. He is working from home on his final project for school, yet I don’t see books or papers anywhere. During the day, friends pack into his small bedroom, spreading out on the carpet to watch Korean soap operas and Hausa films. They smoke cigarettes and steal drips of euphoria from small bottles of cough syrup. In the evenings, they squeeze into cars, blaring pop tunes on their way to an outdoor restaurant where they sit on plastic chairs. They continue smoking, talking, and forgetting.

The key, Bashir says, is to not be alone. “Friends help me stop thinking,” he explains. “If I start thinking, I’ll start going nowhere.”

Reporting for this article was supported by a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation through the Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Go back to Part I: We Will Not Stop Coming or to Part II: The Run of Their Lives