After meeting him on a rescue mission in the Mediterranean Sea, a photographer reconnects with a young migrant from Gambia to document his new life in Italy.

It was 6:40 in the morning when the crew aboard the Iuventa sighted the rubber boat. Aboard were 129 people from Gambia, Senegal, Ghana, Guinea, and Nigeria, among other countries. They had departed six hours prior from the coast of Libya, where they were brought by paid smugglers. Thanks to the rescue mission, conducted by the German NGO Jugend Rettet, all of them survived that day.

I was also on board the Iuventa, documenting the missions and interviewing some of the people being rescued. This is how I met Malick Jeng, one of the 181,436 refugees and migrants who reached Italy by sea in 2016, a year that broke all records in Mediterranean crossings. We spoke as we waited for the Italian Coast Guard vessel to pick them up and bring them to Sicily. Before he left, we exchanged names on Facebook.

Malick, who is now 19, left his hometown of Banjul, the capital of Gambia, five months before that rescue day in August. He walked away alone, without telling his family, like many young people who have attempted the journey to Europe before him. After passing Senegal, he crossed the desert in Mali inside an oil tank, where he nearly suffocated. Once he arrived in Libya, he was imprisoned for a month.

Denounced by the International Organization for Migrations as a “slave market,” Libya, plunged into a power struggle since the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, is home to various armed groups that prey on sub-Saharan migrants in order to make money. They manage the migratory routes to the coasts, as well as the prisons where migrants are often confined and abused, their families extorted to pay for their release.

Malick witnessed the murder of some of his fellow travelers. When he was released from prison, thanks to a payment sent by his family, he immediately got in touch with a smuggler. He was transferred to a “connection center” in the Libyan capital city of Tripoli, where he waited for weeks to be taken to the beach and depart towards Europe.

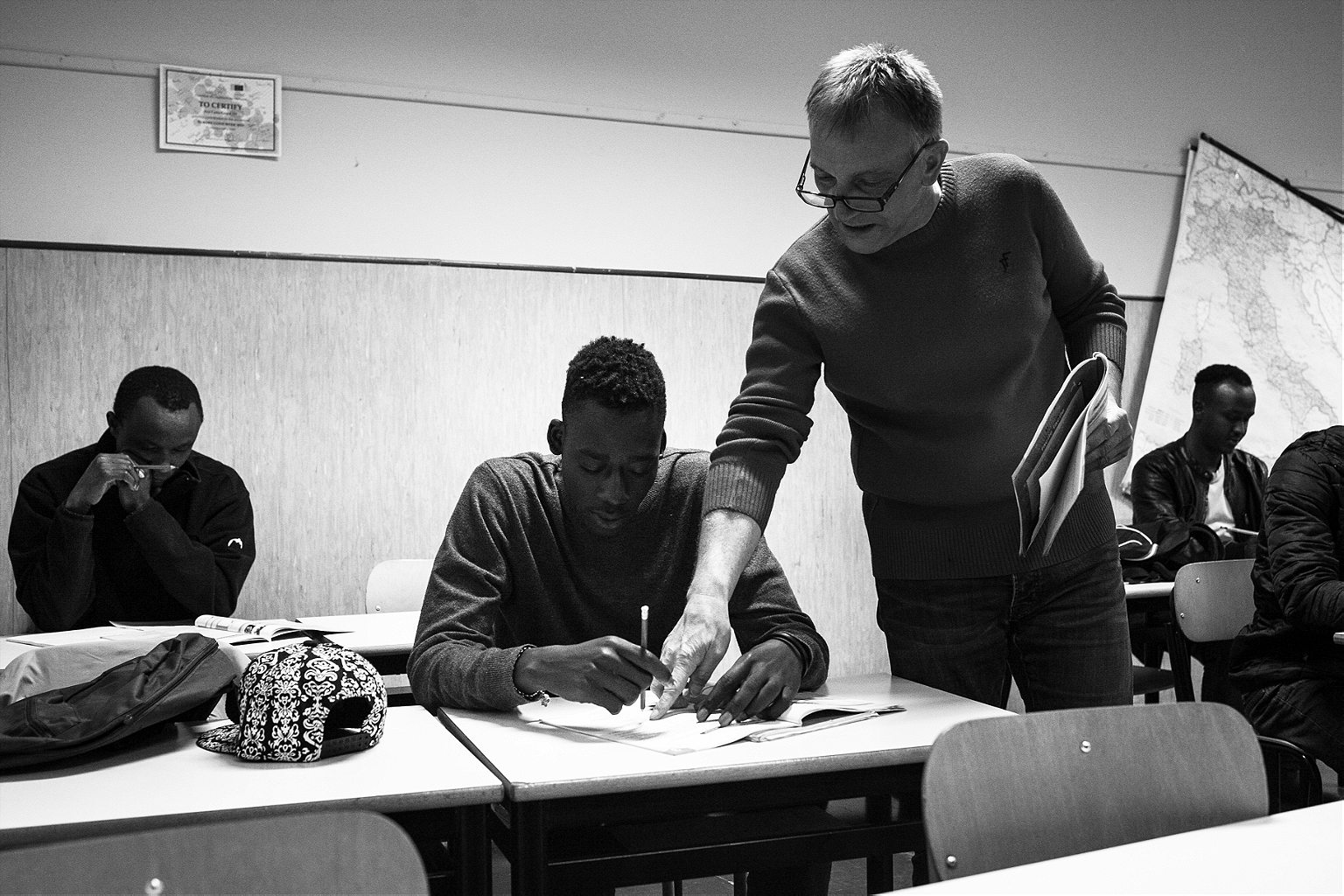

At the end of my three weeks aboard the Iuventa, I started sending Facebook messages to the migrants with whom I had spoken. It took three months for the first replies to come in. Little by little, I heard from Abdoulie, Assan, Henry, Seikou, Maha, Drissa, and Malick. They all told me that they had been saving the money given to them by Italian reception centers, 75 euros a month, to buy basic necessities like clothes and food before getting phones. During this time, they had been unable to send news to their relatives back home.

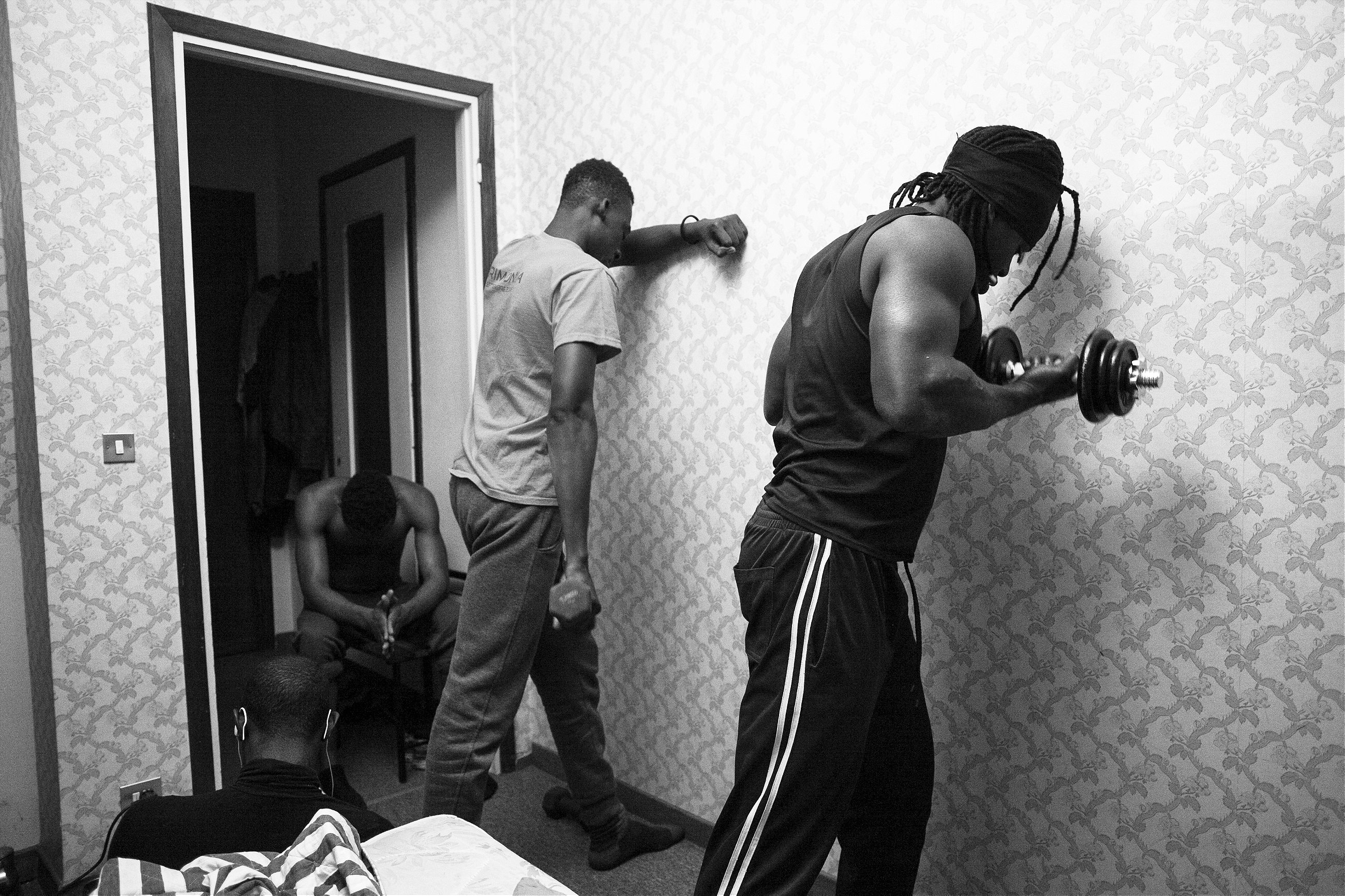

I started speaking with them regularly and planning a trip through various regions of Italy in order to see them again. In January, I started photographing Malick’s transition into a new life.