In Soviet times, sanatoriums were the concrete, clinical heart of Soviet holiday culture. For many in the region, they still are.

Of all the treatments I receive during my three-day stay at Ai Petri, the carbon dioxide bath is one of the most unusual. It involves climbing into a large, white plastic bag that covers my entire body and is tightened around my neck, leaving only my head exposed. It’s the kind of getup that you could imagine seeing on a Japanese game show, except that instead of battling an opponent I am told to lie down, and the bag is pumped full of carbon dioxide.

When I ask the nurse about the purpose of the treatment, the attendant regales me with a long list of health benefits, from weight loss to a cure for insomnia and infertility. The carbon dioxide bath, it seems, is a panacea for all ills. But at Ai Petri, this same exhaustive list, I soon learn, is trotted out regardless of the treatment.

Winter in Crimea lacks the scorching sun and clear blue sky that draws most visitors the rest of the year. But Ai Petri sanatorium, the Soviet-era health spa where I am staying, is bustling. A stone’s throw from the jagged peak of the same name, this concrete high-rise with crescent-shaped balconies has been offering a variety of treatments from leech therapy to salt caves for several decades. But I’m not exactly here for that. I traveled to the south of the Crimean peninsula to make a film for a crowdfunding campaign I’m launching for a photography book project.

A woman holds a jar full of leeches at Ai Petri sanatorium. Video by: Gaetan Nivon.

In addition to customized therapy programs, some guests at Ai Petri are also assigned specific dietary regimes in accordance with their medical requirements. Diet Number Nine, one of the most common here, is prescribed to diabetics and includes foods such as buckwheat, boiled vegetables, and plain salads. Others treat a variety of ailments from obesity to hypertension. It’s a throwback to the Soviet Union, where an annual sojourn at a sanatorium was not only encouraged, but also subsidized by the State so that workers could rest and re-energize on a pseudo-futuristic health regimen in preparation for the working year ahead. Health, not hedonism, was the order of the day.

Apart from the Wi-Fi offered only in the lobby, there have been few changes to Ai Petri and many other sanatoriums throughout the region. Guests today can enjoy the same treatments as Soviet holidaymakers. When I later tell a friend about the oxygen foam I consumed at Ai Petri, she turns nostalgic, describing it as “a taste of her childhood.” The décor, too, remains mostly unchanged. Muted colors, unintentionally distressed furnishings, and potted plants of every size and shape are a staple of sanatorium interior design, resulting in a kind of “granny chic.”

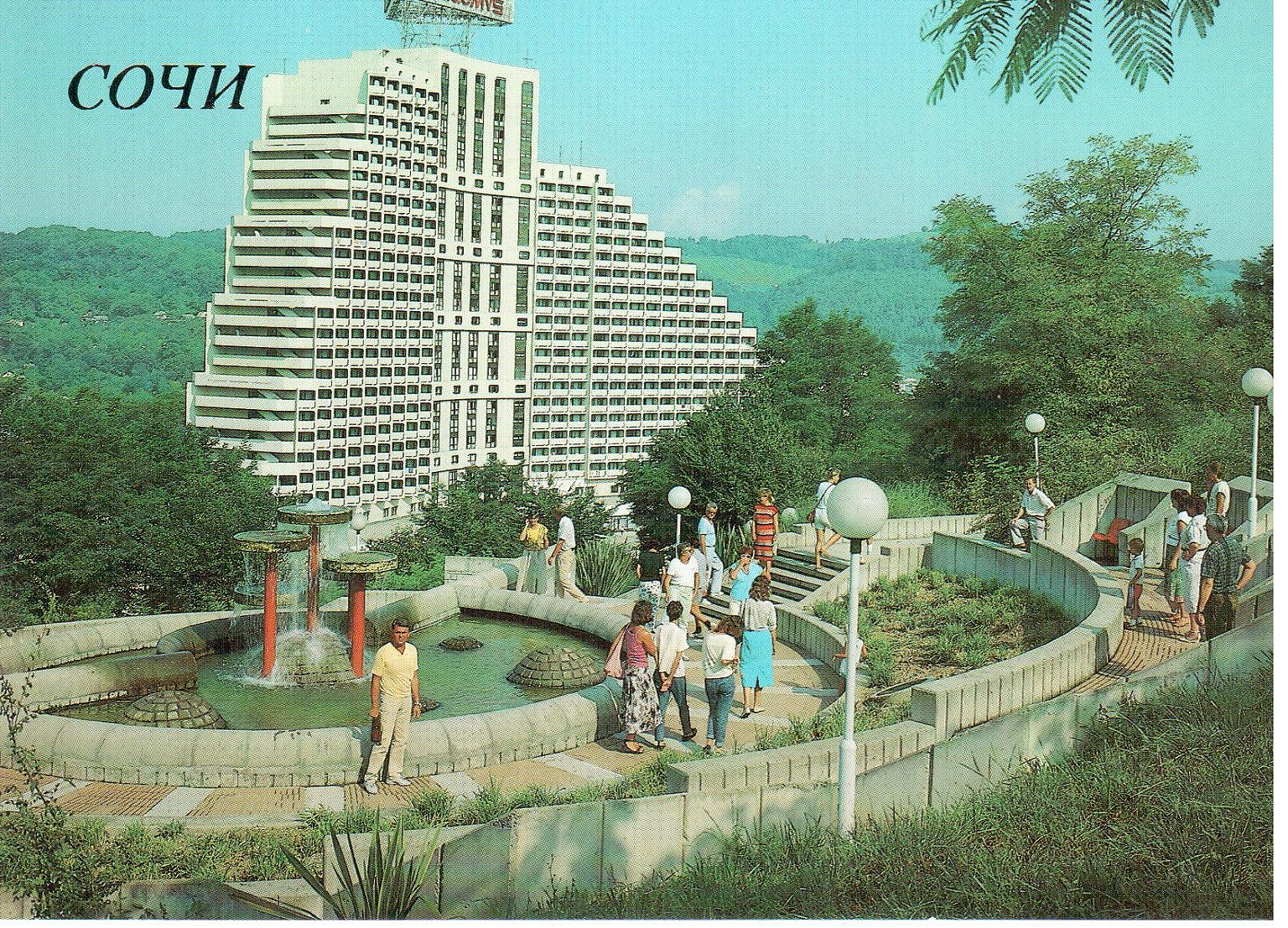

I first became interested in Soviet sanatoriums thanks to the Sochi Project, which sought to document the changes taking place in the Russian city in the run up to the 2014 Winter Olympics. I was captivated by photos of the Metallurg sanatorium: the grand, neoclassical architecture; the unusual-looking contraptions and treatments; and the portraits of guests, simultaneously foreign and familiar. I began reading up on the history of sanatoriums and their place in Soviet culture. When I travelled to Central Asia in early 2015, I had to stop at Khoja Obi Garm, a giant, brutalist block on top of a mountain in Tajikistan, where I hoped speaking Farsi, a language related to Tajik, would enable a more meaningful experience.

As a Londoner, I’m reminded of home by such brutalist architecture, which was once the go-to style for social housing. Yet instead of the usual urban context, here was a building that resembled a council estate nestled among snow-capped peaks, with a picture-perfect blue sky as its backdrop. Located on a rock fault about 2,000 feet above sea level and a short drive from the Tajik capital of Dushanbe, Khoja Obi Garm is famed for its curative, radon-filled waters, which draws visitors from across the country looking to relax and recharge. As with Ai Petri, all meals and treatments are included in the daily price, which, in the case of Khoja Obi Garm, is $18 a night. It’s more Center Parcs than a Four Seasons wellness resort, but the price is not insignificant when you consider the average wage for Tajiks in 2012 was $2,700 a year.

On arrival at Khoja Obi Garm, as is the custom at any sanatorium, I had met with a doctor to receive my tailor-made program of treatments. Assuming he was just making small talk, I had answered “no” to his questions about me being married or having children. A week in Tajikistan had taught me that a person’s marital status was their defining characteristic, and far more important than details such as name or profession. When I said I was single, a look of pity inevitably followed, which turned into horror as soon as I divulged my age. Most Tajik women are married by the age of 20.

“That means you won’t be able to have certain treatments,” the doctor had continued. “For example, one which involves a high-pressured jet of water between your legs.” For Tajiks, any treatment that risks compromising an unmarried woman’s virginity is a no-no. Later, I looked up the treatment in the sanatorium’s brochure, where it was described as “hot treatment radon water sprinkling method between legs.” Descriptions of other treatments were similarly lost in translation, with names such as the “electrical hot chair” and “friction and shaking with medical electrical equipment.”

A guest receives treatment at Ai Petri sanatorium. Video by: Gaetan Nivon.

Apart from another Iranian woman and two Afghan men, I was the only foreigner at Khoja Obi Garm. I was stumped. Why weren’t there more visitors? People traveling to Tajikistan often head straight to the Pamir Mountains, but I couldn’t help but feel that trekkers in the Pamirs were missing out. Not only is Khoja Obi Garm visually striking, but it’s also an opportunity to spend time with locals in the most intimate of environments. The richness of that experience stayed with me. When I returned to London several months later, I pitched a book to the London-based publisher Fuel and received an enthusiastic reply: if I could gather the content for the book, they would cover its design and publication.

I embarked on an adventure to explore these places in more depth, both through the lens of guests who stayed there during the Soviet Union and through the stories of current visitors and employees. I enlisted a team of six photographers—Claudine Doury, Michal Solarski, Egor Rogalev, Dmitry Lookianov, Rene Fietzek and Olya Ivanova—who will be documenting the sanatoriums visually while I write about them. Our plan is to create a book that will inspire and inform readers not only about sanatoriums, but also the post-Soviet space in Central Asia, an under-reported part of the world.

By the time Khoja Obi Garm was built in the second half of the 20th century, the “right to rest” was enshrined in the constitution, with all workers entitled to two weeks off per year. According to the academic Diane Koenker, two types of holidays were available in the Soviet Union. The first involved traveling to a new destination for a cultural experience, while the second consisted in resting at a sanatorium. Both were considered “medically, culturally and socially beneficial.”

For sanatorium stays, trade unions and factory committees provided workers with vouchers that offered discounts, while those who excelled in their fields were rewarded with complimentary visits. Workers were matched with sanatoriums that catered to the medical needs associated with their profession. Mineworkers, for example, would only stay at places that offered oxygen inhalation treatments to help clear the lungs.

For the Soviet government, rest was purposeful. Sanatorium guests received a full program of activities and treatments, and everything from diet to daily walks, and even sunbathing, was monitored by a health professional. At the heart of this approach was Marx’s labor theory of value, which says that the value of a commodity can be measured by the number of hours of labor required to produce it. Rest was viewed as a necessary and natural counterpart to productivity, and an essential part of the economy. This philosophy was thought to be far nobler than that of the West, where holidays were a time to engage in strictly pleasurable, and therefore morally corrupt, pursuits. Occasionally architects were given carte blanche when it came to building sanatoriums so that they could serve as showpieces for Soviet superiority. The more ostentatious, the better, with no expense spared.

The result is a selection of architecturally striking buildings, designed according to the style du jour, from neoclassicism to constructivism and brutalism. Since making it to the front cover of Cosmic Communist Constructions Photographed, a photography book on Soviet brutalist architecture, Druzhba Sanatorium in Crimea has become iconic. A series of stacked cylindrical cogs on top of several columns jutting out of a hill that overlooks the sea, the futuristic-looking sanatorium was mistaken for a rocket launcher by the US Department of Defense when it was built in 1985.

A guest receives treatment at Ai Petri sanatorium. Video by: Gaetan Nivon.

As one might expect, authorities chose sanatorium locations for their temperate climate or proximity to the sea, mountains, hot springs or therapeutic mud. The abundance of crude oil in the Azeri city of Naftalan resulted in a handful of colossal spas being built there in the 1950s, each offering treatments for skin and joint conditions based on the so-called “miracle oil.” Cities along the Black Sea Coast such as Sochi in Russia—home to Stalin’s summer residence—Yalta in Ukraine and Gagra in Abkhazia were prime sanatorium destinations. And although the “right to rest” was egalitarian in theory, vouchers for these sanatoriums were usually reserved for those with the right connections, in summer rather than winter months. The different social strata that socialism proclaimed to eradicate were, in fact, reinforced.

Still, I was struck by the sense of camaraderie among guests throughout my stay at Khoja Obi Garm. Communal treatments such as the pool and the sauna are sex-segregated, and I was welcomed on my first day by a group of corpulent Tajik women in the nude, their breasts bobbing up and down in the water, their smiles flashing gold teeth. We formed a close bond as we spent our days together, swimming, sweating and gossiping.

The evening’s activities were similarly sociable. Guests descended staircase after staircase into the belly of the building where a plush auditorium with red velvet seats and a chandelier awaited them. The first night, an elderly man with luxuriant silver hair and matching mustache hobbled in on crutches to announce he was our DJ for the evening. He exhorted us to sing songs, recite Persian poetry, and dance sequences. Traditional Tajik dancing is similar to Iran’s, with the arms and hands doing the bulk of the work, a little hip action and a lot of swirling.

There is a vibrancy—children chasing each other, a guest playing Beethoven’s fifth symphony on the piano in the reading room, the unforgettable disco in the evenings—that captured my imagination at Ai Petri. Documenting these places is not like documenting urban decay or abandoned Soviet military sites. Yes, the sanatorium buildings can have their own beauty, but I am excited about these and the other locations we’ll explore precisely because they teem with life.

For more information about the book and to donate funds, visit the project’s Kickstarter page.