You have a Palestinian passport. You grew up in Syria. You’re living in Iraq. Your family is in danger. Now what?

Sept. 2, 2015

“Sameer, habibi, how are you? It’s me, Stefano, I am back in Iraq.”

“Stefano! Habibi! I am good now that I hear your voice. I missed you.

“I missed you too. Where are you?

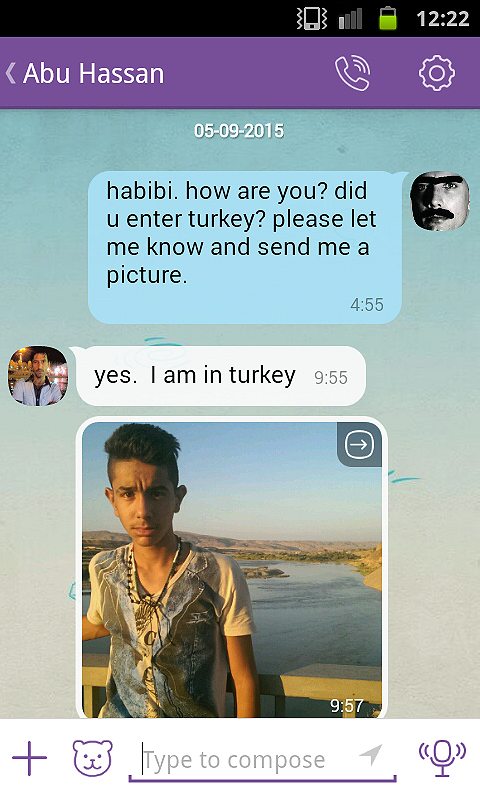

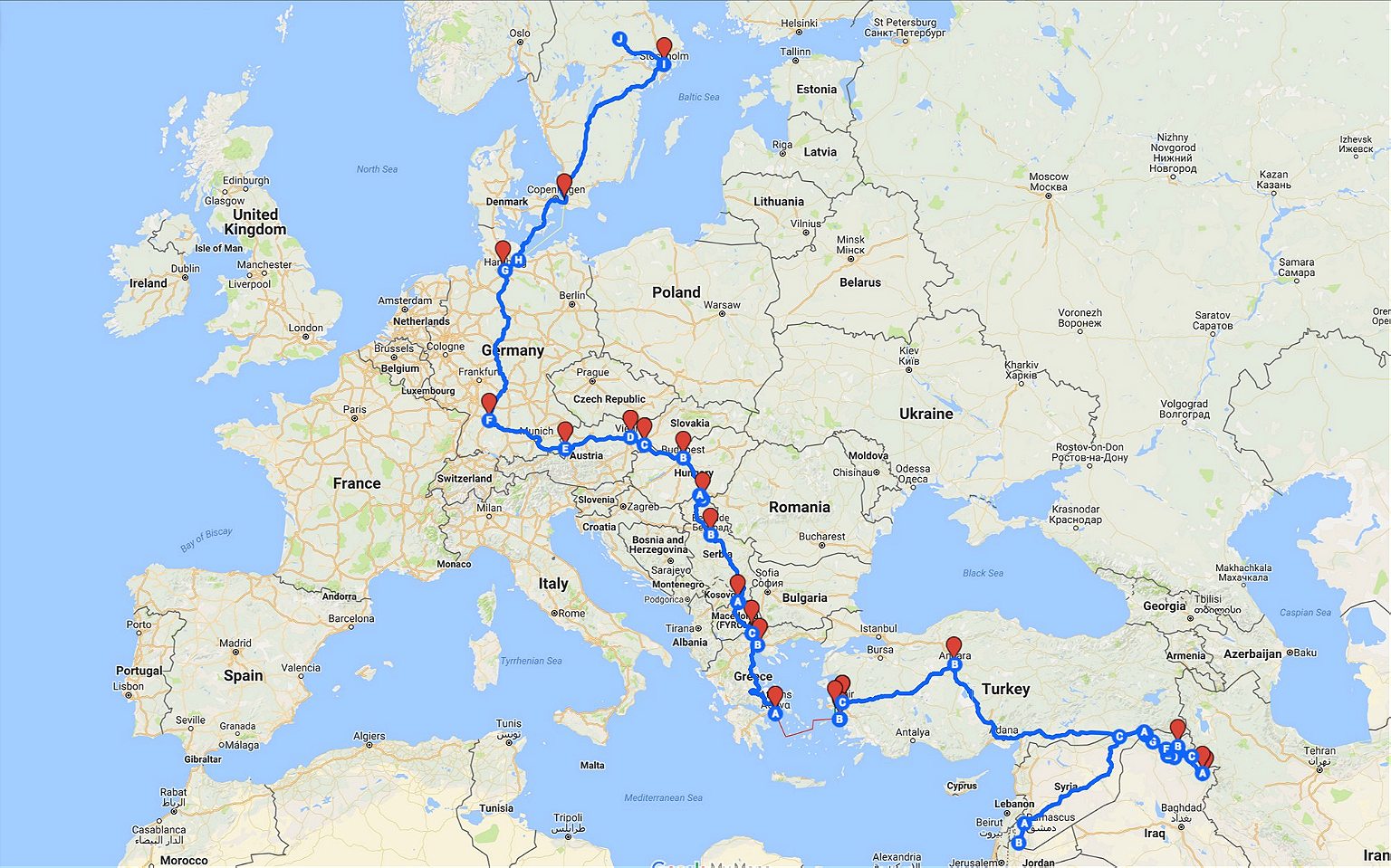

“I am at home, now. Today at 4 p.m. from Sulaiymaniyah I will go to Duhok, then Zakho, Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary, Austria, Germany and then, inshallah, Sweden. It is a long journey.”

Sameer sits next to me, quiet as usual, while Hassan plays with his phone. “The natural world was the first thing I noticed here,” he says in English. “It was so green, luscious, and beautiful. Later it becomes normal, and you wonder about the people: I wanted to meet Swedish people and I could not find them. Maybe sometimes an old person, walking their dog, appears in the streets. Otherwise Arabs, only Arabs,” Sameer says, his eyes fixed on the beauty of the Swedish landscape. He turns to me, suddenly serious. “I hear this word many times these days: refugee. But what is it? What does it really mean? Isn’t it just human? I lived my entire life as a refugee. It is even written on my passport. I am tired. How many times do I have to start from zero again?”

How many times can a person start over again is a question I can’t answer. But I believe that it is necessary to understand what happens to the heart of a person who has everything—happiness, wealth, security, health—and suddenly loses it all.

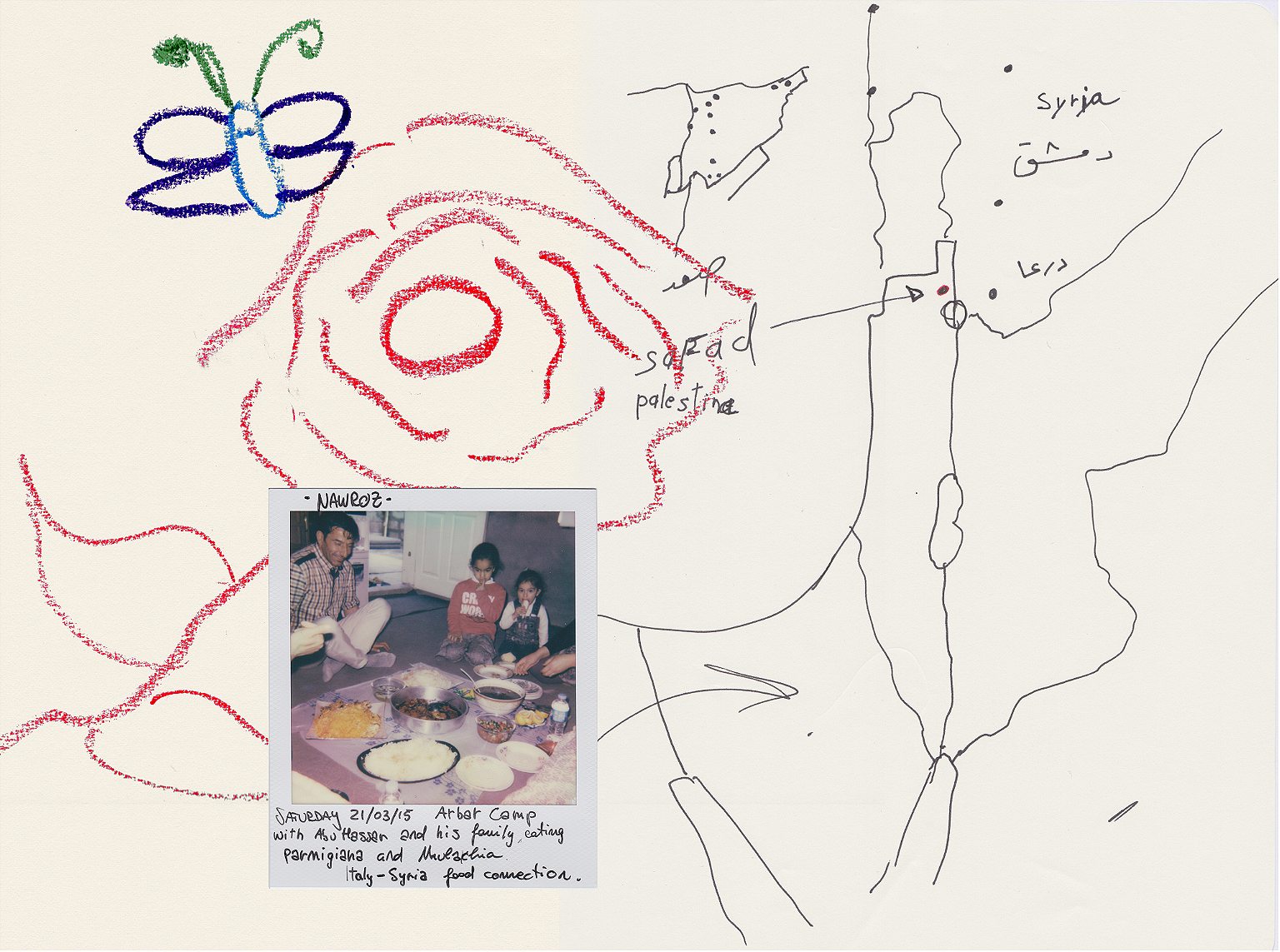

I first met Sameer on March 21, 2015. It was Nawroz, the Kurdish New Year. I had met his wife, Fadya, and their children before, but Sameer was never around; he worked long hours most days. He and his family had been living in the Arbat refugee camp outside of Sulaiymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan for about a year. Finally, we both had a day off and could meet. We decided to cook together, to mix Italian and Syrian cuisines to get a sense of each others’ cultures.

Sameer is a handsome man in his late 40s: not very tall, but with a strong, trim figure; thick, carefully coiffed, dark hair; and a broad, friendly smile. We immediately liked each other. While cooking, he told me that a few days before, he was held at a checkpoint for an entire morning. The Asaysh—the Kurdish security forces—wouldn’t let him pass. “Every day they stop me, they make me get out of the bus, they ask me the same questions and they put my name in their computers. Usually they let me go, but sometimes they just send me back to the camp. They are racist and being Arab is a curse,” he told me with a bitter smile.

Meanwhile, Rama, Sameer’s youngest daughter, sat quietly in a corner making paper boats with her sisters. Sameer was preoccupied. “Maybe I won’t stay here for much longer,” he said suddenly, looking at the sky while smoking a cigarette in the patio. “I am worried for the children; there is no education here, they are being discriminated against, and every day they become more isolated. I want to give them a better future, so when I make enough money I will go to Libya. From there it is cheap to go to Italy by boat.” I tried to persuade him not to go, being aware of the extreme risks they would face.

“It is very dangerous, but what else can I do?” Sameer asked me. “Here we are less than nothing. Arabs, Palestinians, we have no future here. Kurdistan is not for us, it is not our country: Kurdistan is only for the Kurds.” I feared for him, but also understood his motivations. Wouldn’t I do the same in his position?

Sameer’s father was born in the Palestinian city of Safad, from which he fled in 1948 during the Palestinian exodus—known as the Nakba, or disaster, in Arabic—in which more than 700,000 Palestinians were forced to leave their homes. At 12 years old, he walked to Lebanon and then Syria to escape the war between the newly created state of Israel and a coalition of Arab states. He eventually fell in love with a Syrian woman while living in an unofficial refugee camp, and they moved to a house in the Old City neighborhood of Damascus, where Sameer was born in 1969.

Sameer sighed nostalgically. “Ah, the Old City, with the smell of jasmine and coffee, and tapes of Fairuz playing at every corner of every street,” he said, referring to the beloved Lebanese musician. “Not many people know the real nature of Old Damascus, of the neighborhood where I grew up, the Jewish neighborhood. Soon, nobody will remember. Its narrow alleys surrounded by those ancient walls: you could almost hear them whispering when you walked in the evening hours,” he told me while Fadya prepared lunch.

Sameer was 27 when he met Fadya: she was in town for a wedding and stopped in the shop where he worked. She was tall, young, and pretty. He proposed to her the moment they met: they were engaged a few days later and married within a couple of months. At the beginning it wasn’t easy, as Fadya was only 15, perhaps too young to be married to a man almost twice her age, but the two of them learned to respect and care for each other.

Their family grew rapidly; they soon had a son, followed quickly by four daughters. Sameer worked as a successful decorator: they owned two cars and three houses, and he had so much work that he often had to turn down clients. Life was good, even though he was still classified as a Palestinian refugee, and neither he nor his children were granted Syrian citizenship. Other than that, they felt fully integrated into Syrian society and were very happy until the arrival of the “glorious revolution,” when the Syrian people took to the streets, demanding democratic reforms.

Sameer doesn’t like to talk about the revolution: he never believed in it. Like many other Syrians, in the beginning, he didn’t think that the protests would last long. He continued his life as normally as possible, but the crisis only got worse.

“One day, in November 2012, I was with my son in the car when I saw a dead person in the street,” he told me. “I immediately changed my route, and in the next street again there were corpses. I don’t know if he saw them: but what difference does it make? By then, my children could recognize all the different weapons only from their sound. You cannot understand if you have never heard the sound of shelling when the bombs hit the ground. It throws you out of bed, and you feel that it is all over, and all it is left for you to do is to pray,” said Sameer with a heavy voice on the edge of breaking.

Over the following 12 months, things deteriorated quickly and life in Damascus became too dangerous. Work became scarce and then dried up completely: in a time of war, who cares about painting and decorating their houses? He didn’t know how to support his family, so he sold the last car they owned, packed a few bags with Fadya, and they left.

They crossed Syria by bus. When they reached the Iraqi border, they continued on foot, their bags on the back of a donkey, until they reached Iraqi Kurdistan, where one of Sameer’s brothers lived. For a little while, they lived with him and his family in the city of Sulaiymaniyah, but money ran out once more, and they had no choice but to move to the refugee camp. In the beginning, despite the fact that they were the only Arab family in a camp full of Kurds, life there was good. “For a moment we were happy,” he told me, looking at the concrete walls that he built in the autumn of 2014.

Then the discrimination began: as sectarian violence raged in Iraq, Iraqi Kurds became very suspicious of Arabs, especially after June 2014, when ISIS took control of the city of Mosul and millions of Iraqi Arabs poured into the relatively stable Kurdish region.

There are other instances of discrimination besides the constant and humiliating intimidation at the checkpoints surrounding Sulaiymaniyah. One day, when Fadya had to renew her residency card, she was harassed by the officer in charge. “I could not go with her because I was at work. When I came home that evening, I found her in tears: she told me that the officer of the Asayish refused to talk to her in Arabic, and only addressed her using the words ‘animal’ or ‘dirty Arab’. He also tried to touch her and she had to run out of the office to avoid his dirty hands,” he told me. Fadya’s face darkened at the memory.

Sameer focused on his family and his job, trying to ignore the harassment. But his children could not ignore the taunts that made school unbearable. One day, Lama, Sameer’s oldest daughter, described to her mother how the Arabic teacher in her class told them that he hated Arabs and the Arabic language. “What can you do with people like that when they have the education of your children in their hands?” he asked me. “There is no future without education.”

By the end of our lunch, Rama had created a collection of small boats with which she played in a dish full of water. One of the boats fell on its side and was water logged.

While making the crossing to Europe was safer through Turkey, that route was also more expensive. I suggested Sameer delay his plan of going to Libya to cross the Mediterranean Sea, as it was still early in the year, and the water would be frigid. He replied with a smile and promised we would make pizza together soon, while I hoped that summer would bring down the prices of Turkish smugglers.

On Sept. 2, 2015, Sameer left his concrete-block home in the refugee camp. He kissed Fadya and the girls, hugged them one by one, looked them in the eyes, and left with Hassan, his eldest and only son. He took Hassan because he feared if his son turned 18 while they were separated, it would be harder to reunite. Fadya stayed behind with the girls because Sameer didn’t have enough money to bring them all.

Almost immediately after they departed, they were stopped at a checkpoint and held because of their Palestinian refugee passports, which made the guards suspicious. It was late at night, so they rested on the street and tried to catch some sleep among scorpions and snakes while waiting for a friend to pick them up. The next day, a Syrian friend living in Duhok, another city in Iraqi Kurdistan, arrived and spoke at length with the guards, eventually convincing them to let Sameer and his son go. He then drove them to the border with Turkey.

By bus, they travelled without incident to Izmir, where many smugglers’ boats set off for Europe. Sameer had the telephone numbers of several smugglers, but their boats were all full. He didn’t think it would be difficult to find another one as, at the time, the smuggling industry was booming. However, it was late, and they spent the night in a hotel. While having breakfast the next morning, Hassan recognized a young man he had known in Damascus, who was traveling with his whole family. They had found a smuggler, who confirmed that there was still space on the boat.

When Sameer met the smuggler, a skinny and emaciated drunk, he did not trust him. However, they had no choice: he paid the man the equivalent of US$2400 before going to buy life jackets.

In the middle of the night, the smuggler took them to the boat, a small rubber dinghy. When everyone arrived, the smugglers announced they would teach one of the passengers how to steer the boat. Sameer was shocked; he couldn’t imagine how one of the passengers could be capable of navigating to Europe. But there was nothing they could do at that point, so everyone got on board with their bags, and, packed tight as sardines, they sailed off. For hours, they drifted aimlessly. They were cold, wet, tired, and scared, and most of them didn’t know how to swim.

At last, after eight and half hours, the shore of Samos Island, which should have been a one-hour trip, was before them: they had almost died, but they had made it, and many passengers had tears of joy from streaming down their cheeks.

That night, along with hundreds of other people, Sameer and Hassan slept outside. It was cold that night—frigid—and they didn’t have blankets. The first thing they did the next morning was to buy tickets for the ferry to Athens. Then they waited for their papers to be registered by local authorities. In the evening, Sameer went to a café to charge his phone’s battery so that he could call Fadya. There he met Giorgos, a man who was born on the island and was trying to help the people arriving by sea. They sat and drank coffee and spoke at length, mainly about Syria. Giorgos listened carefully to Sameer’s story and then repeated it in Greek to the other people in the bar. The other patrons listened without a word, and Sameer felt a warmth and an empathy he had not felt since he had departed from Kurdistan.

They left the island on a ferry the next day. At noon, they arrived in Athens. Everywhere, there were Arab people shouting “Macedonia, Macedonia,” and inviting the newly arrived refugees to get on buses that they were driving to the border. Sameer and Hassan jumped on a bus and continued their long journey.

The house, which Sameer had built the year before, was simple: a toilet, a patio, a kitchen, and two rooms, one for sleeping one for eating. There was an iron swing for the children, and wild mint, tomatoes, and a palm tree grew alongside the patio. Fadya was in the kitchen. When she saw me she smiled, but her eyes were tired. “I am holding myself together, for the sake of the girls, but I am afraid during the nights. I have never slept without my husband or my son before,” she said to me, while her daughters prepared the room for dinner. Fadya was harassed by local security forces several times when Sameer was still there. I could only imagine her fear now that she was alone with the girls.

SYRIA IS GONE AND IT WILL NEVER COME BACK. EVERYBODY IS DEAD

On the floor, the feast had been laid. There was hummus with tahini, baba ganoush, salads, pizza, chips, and mulukhiyah: jute leaves cooked in a soup with chicken, a staple dish in every Syrian or Palestinian household. I asked Fadya if she could tell me more about their life in Damascus, something we avoided until then because the memories were so painful.

“Ah … Damascus … forgive me if I will cry,” she said. “We were very happy there. My parents were nearby, we had our own house, the children were going to school: it was very different, we were free. Here we have been humiliated and I never felt welcome. There is nothing after Damascus. But Syria is gone and it will never come back. Everybody is dead.”

Tears streamed down her cheeks while memories brought her back to a life that she missed deeply. Then her phone rang. Fadya wiped her eyes and answered anxiously, as she had been waiting for this call for some time. It was Sameer. He had lost his phone in a taxi in Serbia: he was charging the battery with the car cigarette lighter and he left the phone attached to it when they suddenly had to get out. This was the first time he had called in a couple of days. “He said only a few words. He is on his way to Hungary. He sounded very tired: he has not slept for four days. May God protect them, and guide them for the rest of their journey,” she said, while she walked me to the door where the girls were lined up. They waved, chattering and smiling. The four of them with their mother looked so happy, yet so vulnerable.

I think of them while Mahmood, Sameer’s nephew, drives us from the bus station in Västerås, Sweden to their house in Fagersta. Mahmood’s father, Walid—Sameer’s brother—was the first of the family to arrive in Sweden, arriving almost six years ago, well before the war in Syria started. Since then, one by one, all of Sameer’s relatives have left Syria. Nobody is left there.

It’s a crisp evening as we arrive in Fagersta, and I’m told that we’re going to have a barbecue to celebrate the arrival of Isham, Sameer’s youngest brother. Isham arrived a little over a week before with his family. He stayed in Damascus to care for his sickly father: after he died, Isham had nothing left to keep him there. It took him a week and cost $3500 to be smuggled out of Syria with his wife and three children, as his Palestinian passport didn’t allow him to cross the border. They crossed ISIS-controlled territories and were told that at checkpoints, guards were chopping off people’s fingers if they found cigarettes in their cars. In Turkey, it cost another $3500 to cross the sea. The rest of the journey to Sweden cost about $700.

While a family discussion about the Syrian revolution inevitably heats up, with some supporting it and others blaming it for the destruction of their lives, Sameer and I withdraw from the gathering and find a quiet place so he can tell me about the last part of the journey that brought him here.

Sameer and Hassan were terrified as they approached Hungary. They had heard that the police were violent and would fingerprint them, making it impossible for them to travel any further. They recognized the border when they saw fences, barbed wire, and police everywhere. Then they saw the railway and a line of people, fellow refugees. When their time to cross came, nobody bothered asking for anything; instead, they were welcomed by NGOs into a small camp, where they rested for a while. They learned they were a few hundred feet from the checkpoint where the Hungarian police, purportedly, were taking fingerprints. Sameer and Hassan turned the other way and silently walked through thick orchards. At the other end of the field, taxis were waiting. The drivers’ prices were outrageous, but at least they would take them to the station in Budapest and not ask questions.

When they reached the last train station in Hungary, the Hungarian police walked with them until they entered Austria, which, for Sameer, was their real crossing into Europe. Things were different there, better organized. In a large building, there were about 2,000 beds, and food and beverages were available. Sameer described it as extraordinary and unexpected. For the first time in a long while, he really felt welcome.

Then they entered Germany by train. At the border, in a small village (Sameer doesn’t remember the name) German officials took all the refugees off the train to register them and then they put them on another train to Stuttgart. Sameer was extremely tired, and his memories are confused: he remembers only being in a camp where everything was provided free of charge. There were even showers, which made him very happy, as the last shower he took had been in Turkey over a week before.

From there on, in the heart of Europe, they were free to go anywhere they wanted without anybody checking their papers or stopping them, something novel, as they were used to Iraq, where they could not even leave their neighborhood without difficulty. However, they didn’t have any idea where they were or what to do next.

But each time they felt lost, the German people helped them. When they arrived in Hamburg and didn’t know where to go, a woman approached them and explained in English how they could reach Lübeck, where they could take a boat to Sweden. Then she bought tickets for them, put them on the right train, and made sure they knew where to get off.

“In Lübeck, a couple of young German volunteers took us in their car and first drove us to a house where we could eat, drink, and rest, before driving us to the pier, where they gave us warm clothes, shampoo, toothbrushes. They did not leave us until the boat sailed off: may God protect them always,” he tells me, remembering the people who made him and Hassan feel welcome in this faraway, foreign land.

When they arrived in Malmö, Sameer finally managed to buy a new phone and call his family to let them know that he was in Sweden. His brothers picked him and Hassan up in Stockholm and they went home. Nobody stopped them. They were free, at last. “It took us 17 days to travel more than 6,000 kilometers across nine countries. The most difficult part of the whole trip was to get out of Kurdistan. And that is because we are Arabs and maybe for them we are animals,” he tells me, finishing his incredible account on a bitter note as memories of how badly they were treated in Kurdistan surface again and worries for his wife and daughters cause deep worry lines to appear across his forehead.

It was a mild autumn in Sweden and across the whole of Europe: perhaps nature’s act of mercy for those who were late in crossing the sea. Every day, refugees arrive in Greece; every day, they cross half of Europe. On our screens and in our newspapers, there is an endless march north, as if more than simply escaping, people want to go as far as possible from their destroyed houses, from their past lives.

Like every good Syrian, Sameer has had a cup of coffee in his hands since before he was fully awake. Fairuz plays on the laptop, as if we were back in Damascus. But outside, the leaves are yellow and fog blankets the landscape. This is not Syria.

Two Iraqi men stroll in front of the window and wave. Sameer laughs, wondering again where the Swedes are. Inside, he smokes and stares into the distance. Fadya calls, right on time, as she does every morning. She asks about Hassan, who she worries about: he has never been away from his mother. The girls giggle in the background. The youngest, Rama, calls her father “an animal” because he is not there to take care of her. “She is very honest, the little one,” he says and laughs, but there is profound sadness in his dark eyes.

Sameer had been in Sweden for 40 days: he was very sick when he arrived and needed to rest. Now he looks at things one by one. First, he needs to take care of Fadya and the girls in Iraq, who are running out of money. He isn’t allowed to work in Sweden until he gets his residency permit, but he needs to send them funds soon. The second thing is getting Hassan back into his studies; they were able to register him in a local school. Sameer is also going back to school, to learn his new language. He has already started on his own, with a book, the newspapers, the television. Then there is the residency permit, which unfortunately is not in his hands; only after he gets his papers can he ask for family reunification.

“Sometimes I get worried and I think of how I am going to live and how I am going to feed my family,” he tells me over a breakfast of hummus, olives, bread, eggs, and tea. “Other times, I see us in a big house where the girls will share two rooms, Hassan will have a room all for himself, while Fadya and I will have our own. I see a large living room, with a television, and a kitchen, comfortable and fully equipped. I hope I will be able to get it, but more than this, I hope for the children to integrate into this society. That is the most important thing. It is for this reason that I am thinking to move to the north [of Sweden]. Yes, because there are no Swedish people here. They are all Iraqis, Syrians, Afghans, Somalis. You can go to the Arab café, to the Arab shop: everybody is Arab. But I left Syria and Iraq, and I want to be out of that society now. I don’t want to be part of the same community because I cannot trust my own people anymore. They say one thing but in their heart they mean something else. You know, I miss Damascus tremendously. I miss my entire life in Damascus: my memories, my childhood, even the walls of my school. But all of it now is gone, forever, destroyed by people who cannot think with their own heads. Those are nations that ride the waves, nations that change colors like chameleons: do you think you can trust them? I came to Sweden to give a future to my children, to give them a nationality, a proper education and certain values. These are the values of Europe now, not the values of the Middle East. Therefore, we will go to the north and we will start all over again. This time, maybe, for the last time.”

By Dec. 2015, Fadya could no longer wait: she decided to leave Arbat with her daughters. They made the same journey her husband and Hassan did in Sept. and arrived in Sweden before Christmas. They now live together in a three-room house in Fagersta, Sweden. All the children go to school and are rapidly learning Swedish.