Step inside the traditional Indonesian factory that makes ugly noodles.

It’s still early morning when I land in Yogyakarta, the last remaining sultanate in Indonesia. I flew in from my home in Bali to meet Yasir Feri, the owner of a legendary noodle factory in the nearby village of Bendo. After a quick breakfast, I jump on a motorcycle and drive for two hours through the lush vegetation and rice paddy fields.

Feri is just back from the market, where he has been selling his famous noodles. As I arrive, one of his workers greets me with a smile. He carries a large bundle of grass. “I must feed the cow first before he can work with us,” he says.

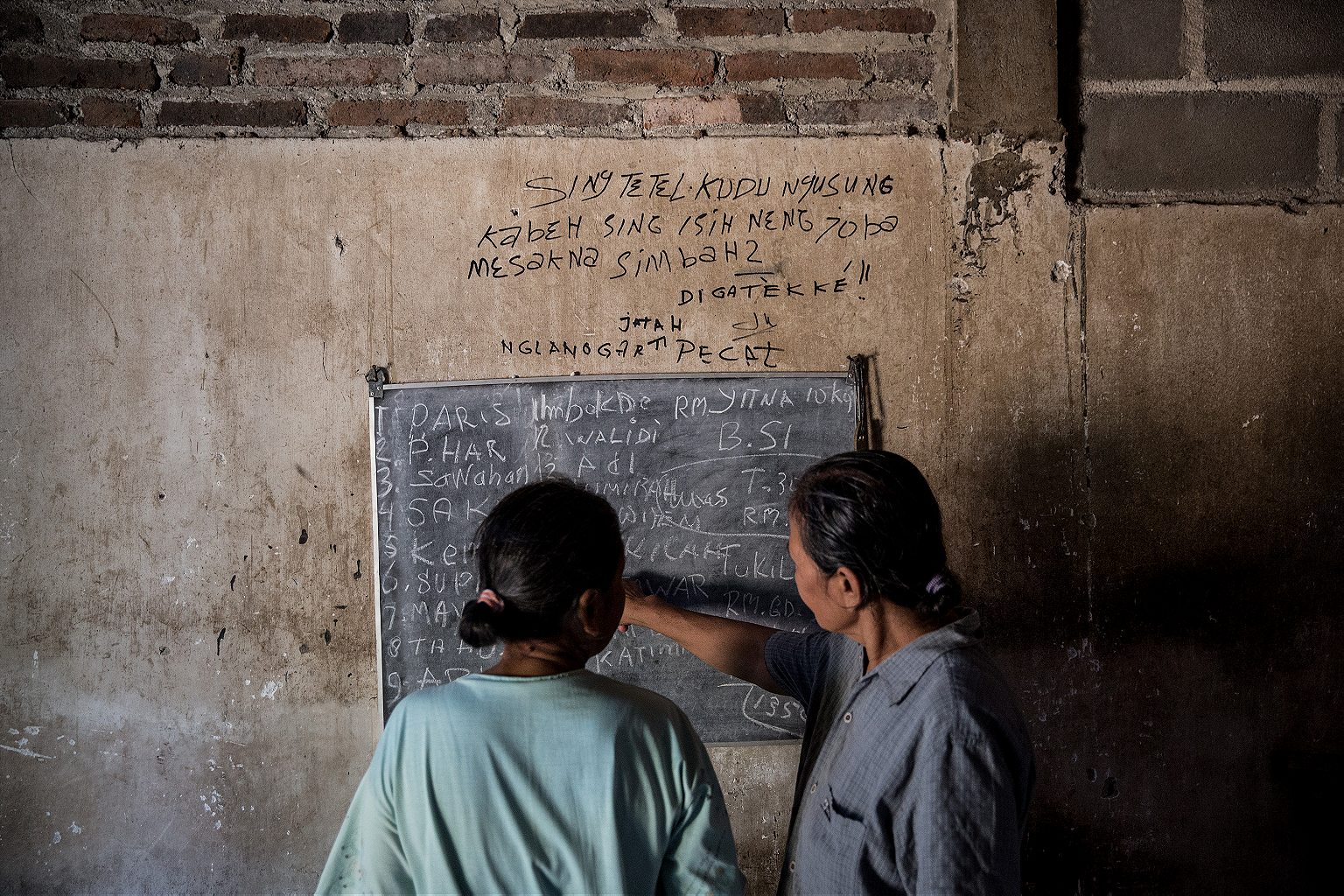

In this traditional factory, about 30 men from nearby villages make mie lethek, meaning dull or ugly noodles. The name comes from their grayish color, caused by sweet potato flour and dried cassava.

Yasir Feri’s factory is a family business. In the 1940s, his late grandfather, who was from Yemen, met his grandmother, a woman of Chinese descent, and they started the business together. “At that time, many people were making noodle mixture from rice and corn,” explains Feri. “To be competitive, my grandmother tried making noodles from cassava.” The noodle-making method was also his grandmother’s technique.

In the high-ceilinged factory, sunlight streams through wooden windows. Songs in Javanese reverberate out of an old radio. To prepare the flour, Feri uses a six-foot-wide mortar and a stone cylinder attached to a cow: with the help of three workers, the cow pulls the one-ton cylinder over the starches for one to three hours. On the other side, the noodles are manually pressed into shape and steamed in a traditional giant stove.

The noodles must dry in the sun for a day before they are sold at the market. A little more than two pounds of mie lethek costs around 8,000 Indonesian rupiah, or 60 cents.

Very few people make these noodles because the production process is so arduous. Yet Feri says he can churn out 10 tons of mie lethek in a month, about 100 pounds of which are sent to the Department of Agriculture to be delivered to the residence of the former President of Indonesia. The noodles’ distinct flavor has made them famous throughout the country, and they have become synonymous with the culinary traditions of Yogyakarta.