A new cultural center in Buenos Aires reflects the good and bad of the Kirchner political dynasty.

For millions of Argentinians, the late Nestor Kirchner, the political strongman who ruled Argentina between 2003 and 2007, was a colossus. He took on the banks, the International Monetary Fund, and George W. Bush. He was an iconoclast, so the myth goes, who dragged Argentina from the flames of its biggest economic meltdown and restored pride to a nation on its knees.

The Palacio de Correos in downtown Buenos Aires is unmistakably a colossus. Built over four separate decades, between 1888 and 1928, the city’s old central post office is the biggest, most beautiful example of Beaux-Arts architecture in Argentina’s capital. It occupies an entire city block; a robust palace of muscular columns and marbled walls, a once gilded sorting post for correspondence arriving from the old world to the new.

The Kirchners—Nestor and Cristina, who succeeded her husband as president in 2007—handpicked the old postal palace as the site for their legacy project, the biggest cultural center in Latin America, no less. The Kirchners promised to convert the old post office into an arts space that would be as impressive as the Centro Pompidou, a gift to the nation that would bring art to the masses, free of cost.

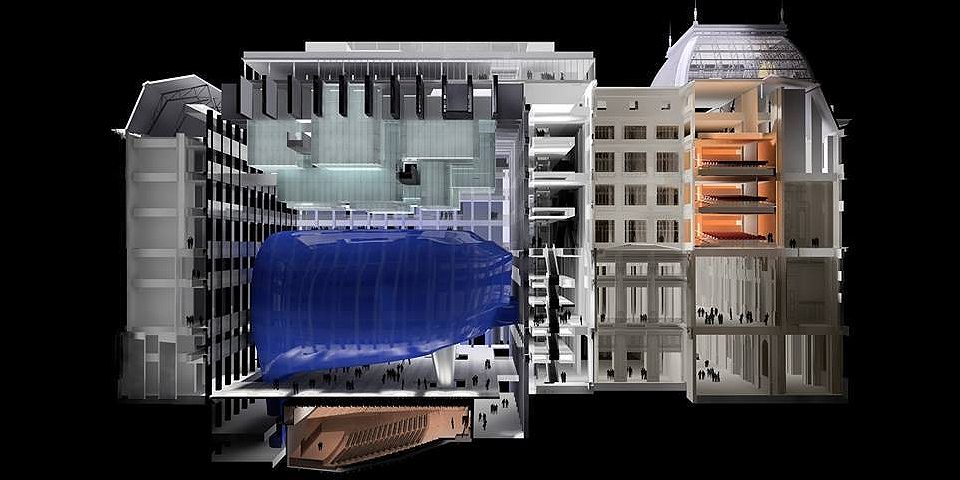

It would transform a floor space of 115,000 square meters into a state-of-the-art cultural center with capacity for more than 50 separate concert rooms, a museum of modern art, and, to top it all, a central auditorium with seating space for nearly 2,000 spectators. It would be a fitting monument to a political power couple who, in more than a decade of leftist rule, brought deep social and economic change to Argentina.

In May 2015 this grand vision became reality. Cristina Kirchner, now a widow following her husband’s sudden death, opened the brand new Centro Cultural Kirchner (Kirchner Cultural Center) to great fanfare and greater controversy. Close to tears, she dedicated it to her late husband’s memory.

The lavish budget for the conversion had spiraled so much it rivalled the cost of major contemporaneous work on Rome’s Coliseum. But Cristina’s supporters didn’t mind; they believed the project to be a loving homage to her late husband. Critics, however, called it pharaonic folly, a vanity project befitting the couple’s 12 years in power.

The new cultural center polarizes opinion. In fact, it has become a symbol of Kirchner rule itself.

My partner and I crane our necks upwards at the building’s façade, all weighty classicism and as big as a cliff-face. We climb a pile of steps. There are three sets of open double doors. We choose the ones on the left, where two members of La Cámpora, the militant youth wing of Cristina Kirchner’s political party. Remunerated staff at the cultural center are in the pay of the Argentinian state, and according to local media reports a slice of their state-funded wage is funneled back to the political party Cristina heads. (Argentinians commonly refer to Ms. Kirchner by her first name.)

One of the guards, whose crimpled t-shirt is emblazoned with the Kirchner brand, informs us that the entrance is at the next doorway. There, a second foot soldier welcomes us to the Centro Cultural Kirchner and a young man tells us about the center and its exhibitions.

Hero-worship informed the designation of the old postal palace as a legacy site. Nestor Kirchner’s father spent his working life in the employ of Argentina’s postal service. For Cristina, it was her political heroine, Eva Perón. In the 1940s the charismatic former First Lady ran a charitable foundation from an office at the old postal palace.

The cultural center preserves Evita’s office in-situ. Its floors are crafted from French oak, the walls lined with silk cloth. From a singularly luxurious space, Evita sat in the manner of a medieval queen, dispatching gifts and monies to the poor and destitute, while receiving hundreds more in person each day.

José María Areilza, the Spanish Ambassador of the day, wrote in 1946:

It was non-stop clamor. A racket of hundreds of people waiting for hours to be received by Her: workers’ commissions, union representatives, disheveled village women with children… a gaucho family… peasants… secretaries, senators, deputies, governors, the president of the Central Bank. In the midst of this apparent chaos, this noisy, confusing, even insane bazaar, Evita heard the most diverse petitions.

Today, a corner of the office conserves letters piled from floor to ceiling, once posted by Argentinians to Evita in solicitation of her beneficence. Hundreds of packaged gifts—children’s toys, tea sets, bicycles, Christmas cakes—are stacked as if ready to be dispatched in return.

On an oak desk there rests an original letter handwritten by the First Lady to a young schoolgirl. In neat script, Evita congratulates the girl on her exam results and by way of reward encloses holiday vouchers and train tickets to the Córdoba sierras. This was Evita the venerated; protector of the poor.

It is almost certain the Kirchners chose the postal palace because of its links to Evita and General Juan Domingo Perón. A vein of populist rule runs through Argentina’s modern history, bookended by the Peróns in the 1940s and the Kirchners in the modern day.

Together, the Kirchners became the most powerful political couple in Argentina since the 1940s. Nestor was a pragmatic like the old General; Cristina often invokes Evita; so much so that her critics call her the Botox Evita, an allusion to a president who is rumored to have undergone cosmetic surgery but also someone who, her critics say, is a fake. They point to Cristina’s tendency to pontificate on poverty standing at the dispatch box, all dazzling jewels and luxurious hair extensions, while at the same time overseeing an 800 percent leap—according to figures released by Kirchner herself—in the value of her family’s wealth during 12 years in power.

But there are key differences. In 1955, a military coup ousted the general. In a democratic era free of the military coup, the Kirchners’ cycle has been permitted to reach an exhausted end. Only not before creating deep divisions.

To understand the violent birth of that cycle, one must go back to the past and to the devastation visited upon Argentina in 2001 and 2002. At that time Argentina suffered the biggest economic meltdown in its history, when the country’s financial system was crushed under a mountain of foreign debt and austerity programs imposed on it by the International Monetary Fund.

I was a reporter in Buenos Aires at the time and witnessed the struggles for the first time. A review of my notes finds the following excerpts:

Live TV footage: On a highway, a truck carrying livestock to market is stopped and overturned by men, wielding machetes. The men unload the cattle, which they proceed to slaughter at the roadside. Wives and children flee with raw cuts of beef.

An immigrant Chinese man and supermarket owner stand in tears outside his business. Looters strip his store and exit carrying everything from tinned food to the man’s tinseled Christmas tree. (A reporter from La Nación newspaper later attempted to track down the weeping Chinese man. It turns out he took his own life shortly after the episode I described in my notebook.)

Police fire live ammunition on protestors in the main plaza in Buenos Aires, killing dozens in a single afternoon.

President Fernando de la Rúa flees the Pink House by rooftop helicopter lest he be lynched at roadside.

Then—so the story goes—came the Kirchners to drag Argentina phoenix-like from the flames of its earlier collapse. “Never again,” Nestor Kirchner said in his inaugural speech. He promised a new model, which would defend Argentina’s economic sovereignty and end wealth iniquity.

At the Kirchner Cultural Centre, the Nestor Kirchner Salon celebrates this narrative. The great myth, critics say. In video clips we see Nestor Kirchner’s inaugural address. “The expression of the popular will,” he says “is a moral obligation.” Here is Kirchner announcing the cancellation of Argentina’s debts before the hated IMF. There is Kirchner standing up to George W. Bush at a regional summit, after rejecting a proposal for a free-trade zone of the Americas.

The Kirchners were never bad at vulgarity

Much of this is true, though the display strays into vulgar vainglory. (The Kirchners were never bad at vulgarity: Cristina once urged Argentinians to forgo the beefsteak for fish, hinting the latter had spiked Nestor’s virility.) Nestor Kirchner was indeed a political titan who restored growth to Argentina. But there were fortuitous factors. Not least of which was China’s entry into the World Trade Organization at the end of 2001, which saw global demand for agricultural commodities explode. The boom funded lavish spending by the Kirchners on welfare and price-subsidy programs.

It is tempting to view the full power of the Kirchner state as on display at the center. It is not just the gargantuan size of this place, itself a reminder of the omnipotence of centralized government. It is in the almost total absence of visitor signs. Where one might expect to read a sign, two T-shirted loyalists are at hand to advise where to go. Where a locked door might suffice, the doorway is left open and two La Cámpora activists are stationed to remind the entrance to this exhibition is a further 10 meters along.

Jobs for the boys and girls, one might say. The chaotic organization of a new cultural center with teething problems, others suggest. Yet that the new cultural center is massively overstaffed is undeniable, and this has sparked fears of there being something much more insidious at play.

Critics call the center a metaphor for a less appealing aspect of Kirchner rule: the disempowerment of the individual before the state; the creation of a sense of dependency, they say; the subtle curbing, even, of one’s free will. Either way, it is maddening to be subject to instructions every three minutes (or so it seems) by well-meaning staff. One emits a silent scream. The instinctive desire to follow one’s own path meets only frustration.

The site’s centerpiece is the Blue Whale, a world-class concert hall built in the shape of a whale, a free standing structure that spans the giant sorting area of the old building, where it rests on mammoth concrete legs. It seats 1,800 and is the new residence of the Argentine National Symphony Orchestra. It is a stunning work, emblematic of a free arts space that splices the elegance of the old postal palace—all giant archways and cascading chandeliers—with the thrilling contemporaneity of modern performance art.

But an officious guard blocks our entry to the Blue Whale, because, he says, we are not wearing visitors’ badges. We weren’t given any, we retort. And so it goes, back and forth. A second staff member is dispatched to fetch the badges. We are not obliged to register our details on collect; nevertheless, it is only with badges can we enter the whale. It feels pointless, representative of a bloated, inefficient state. The episode is instructive, like the conversation we overhear on our exiting the new hall.

A La Cámpora girl has ended her guided tour with a group of visitors. The girl asks her group to say what springs to mind when they consider the center. “The importance of the state,” says one, to murmurs of consensus. The Kirchners had an avid audience. Theirs was a reciprocal relationship with millions.

In late 2010, Nestor Kirchner died suddenly from a heart attack. A mourning Cristina Kirchner wore black and turned to youth for succor. She empowered La Cámpora. A head-nosed pragmatist, Nestor had advised the ideological youths to get back to him once they had graduated university. Cristina, driven by emotion and alone in mourning, embraced them.

Key positions in national government and industry were awarded to the top rung of La Cámpora officials. Lower down, thousands of fanatical, younger supporters found employment by the state at places like the cultural center. On orders, they staged massive political rallies at which they urged their lonely president to fight “the right-wing conspiracy” being waged against her. La Cámpora became a hate word for the middle classes.

Ideologue, where her husband was pragmatist, Cristina sought reform of the independent judiciary and opposition media. Democratic reform of conservative bastions, said Cristina; attacks on opposition judges and press, cried critics. Cristina wanted judges to be chosen by popular vote, to bend to the popular will. The Supreme Court knocked her back on grounds of unconstitutionality.

Cristina is sometimes fascinating to watch. She is a brilliant orator who believes in the reality of her own rhetoric. Hers was the antithesis of prosaic orthodoxy. It was a pseudo-revolution that dangled hope before a fanatical following; an alternative to life’s humdrum realities. La Cámpora, for one, chose notoriety over anonymity. Certainly, the outsiders—the right-wing foreign media for one—never got it. They never understood the Botox Evita, the fist-waving populism, but millions in Argentina did; lest we forget, there were three election victories.

But it unraveled. Global commodity prices fell. The well ran dry and Cristina’s government took to printing money to fund the welfare programs that underpinned its populist rule. The middle-classes, already spooked by creeping authoritarianism and corruption scandals, reacted badly as soaring inflation eroded savings. Restrictions on currency exchange hardened criticisms.

The Kirchners did much good for Argentina. They defended jobs and righted the bloody wrongs of Argentina’s 1970s dictatorship when subjecting military officers to criminal trial for the first time.

They enshrined the right to gay marriage. But the economy has not grown in four years, the annual inflation rate rages at 30 percent according to independent estimates. The nation is split.

Then there’s the cultural center. It is the newest of some 170 sites in Argentina—including roads, schools, a gas pipeline, hydroelectric dam, and football stadium—named to honor the titan, in what critics call a cult of personality. It is a monumental symbol of polarization.

At dinner parties in Buenos Aires I’ve made attempts to talk about the center with middle-class acquaintances. I’ve avoided its political angle and focused solely on its fantastic art spaces. I am stonewalled with silence. For these people, nothing Kirchner does can ever be considered good. In other company, I have criticized aspects of Kirchner rule. People have left the table.

In national elections in December, Cristina was constitutionally barred from running for re-election. In her absence, the conservative Mauricio Macri defeated the ruling party candidate. Argentina voted for change after 12 years of Kirchner rule and will embrace a new era of right-wing conservatism.

Macri, who was born into of Argentina’s richest families, is a darling of the markets. He has promised to open up Argentina’s economy. He has pledged to change the name of the cultural center, too. It is too divisive, Macri says. A parliamentary bill is already in the offing.

One wonders what will happen to the kids at the center. Some of them dream of a second coming, praying the 62-year-old Cristina will make a comeback like the general once did. There is speculation of a renewed bid for the presidency in 2019. But four years is a lifetime in politics, and besides, Cristina has other problems. Her family business is subject to a criminal investigation into money laundering allegations, which Cristina has denied.

We exit and look up at a cliff-face of white stone. Above the entrance to the building, the inscription Centro Cultural Kirchner is writ large on a plaque made of stone. Hidden from view beneath it, there lies a second stone slab that is carved with the words Palacio Correos. The old postal palace’s status as a protected building had prevented the removal of this original signage, prompting a compromise in which the Kirchner name was simply bolted on top. That, like the political model the Kirchners built, will now be dismantled. It is not the toppling of Saddam or Lenin, but it will be significant for its symbolism, nonetheless. The colossus is dead and Cristina’s populism has fallen.

In Argentina, nothing is set in stone.