In rural Ontario, a decrepit nuclear fallout shelter awaits the end times.

Set into a grassy hill, the metal door opens with a deep clunk. A blast of frigid, dank air escapes from within. My colleague and I affix particle masks over our faces; we’ve been warned of the mold that has spread throughout the underground structure we’re about to enter.

Our guide, Bruce Beach, leads us into the structure’s ante-chamber, his giant white beard ruffling in the cold breeze rising from the blackness inside. We descend down the gradual incline—five, ten, fifteen, twenty feet underground. The air is thick and heavy, an odd mix of humidity and chill. Condensation flickers and drips as we trace our lights over the support beams of a conveyor belt used to ferry goods and supplies down below ground, now fully encrusted in rust.

Turning left, a long hall opens in front of us, the far end disappearing in the inky darkness. I feel uneasy being this far underground, and I constantly have to duck my 6’5” frame below the low ceilings; the whole experience feels like I’m living out some kind of zombie video game.

Slowly making our way down the long hallway, we turn into the first room we come across. There’s a simple red tag above the five-foot doorway. “This is the decontamination room,” Beach says. Decontamination for what? “Decontamination from nuclear fallout, radiation, radioactive particles, the like,” he replies. “Anyone who comes down here post-nuclear war will have to be decontaminated.”

We’re standing in the center of what has come to be known as ARK 2, a privately financed nuclear fallout shelter nestled in the rolling backcountry hills of rural Ontario, Canada, and built by Beach’s own hands more than three decades ago. The shelter’s backstory connects the Canadian federal government, the country’s most popular prime minister, diverted millions, an ongoing battle with local authorities, a determined belief in the end of the world as we know it, and the hope for a better future.

Beach is a man of few words, but when he does chime in, the room listens. A solid, curmudgeonly man in his mid-80s, with a Santa Claus beard and a slight limp in his step, Beach is known throughout North America as the quintessential “prepper”: someone who is ready and actively preparing for the dissolution of society and the need to reconstruct after “the crash.” Beach has written two books on the topic, Society After Doomsday and TRIAD Individual Networking: Preparedness For Disastrous Times. Not your typical bedside reading.

Beach’s concern about nuclear war and the need for societal reconstruction began while he was in the United States Air Force in the 1950s, guiding intercontinental bombers as an air traffic controller at Dobbins Air Force base in Georgia. Seeing the realities of the Cold War firsthand led Beach to think about planning for the worst. He started keeping a bug-out bag, filled with all the necessities to live and survive on the road in the case of emergency, packed and ready.

In the 1970s Beach and his wife, Jean, moved to Canada into the very small, very rural town of Horning’s Mills, population 500. The land that would eventually house ARK 2, he says, “was Jean’s grandfathers; it was the mill.” Located beside a cascading waterfall and tucked into the rolling hills, it was an idyllic setting for a modern day ark.

Inside the shelter I smack my head on the low ceiling with a solid crack. In front of me, Beach continues guiding us through the complex, no flashlight, no concern. He knows these corridors.

He shows us the bunk rooms, cots and beds stacked and aligned tightly. We walk though functioning bathrooms and a boardroom, past kitchens and wash facilities, and finally through a full dental operating theater, complete with X-ray machine.

Beach learned how to build shelters when he was still living in the United States. He breaks down his process: “You need to dig a hole, put the buses in, fill it up with concrete, and then back fill the hole.” It’s no simple task, and it isn’t cheap. One of the underlying mysteries of ARK 2 is how Beach financed it—the project was rumored to cost upwards of a million dollars.

According to local government sources, Beach was commissioned by the Canadian government under the charismatic prime minister Pierre Trudeau to build a bunker in the Cold War-era 1980s, when the threat of nuclear war was ever-present. It was to be a bunker not unlike those he had built in Utah and Idaho in previous decades. However, local sources—a regional councilor and a former councilor, who is a current local museum employee, both of whom requested anonymity—suggested that the majority of the funds provided by the federal government never made it to the government-commissioned bunker, and were instead diverted toward a separate project: ARK 2.

Beach broke ground on the shelter in 1984. He obtained 41 school buses to use as prefabricated subterranean structures. “We put [the school buses] in in ‘85,” Beach says, adding that it’s “still a work in progress.” As we walk through the shelter, Beach mentions a long list of things that need to be updated, added, and fixed.

Up until just a few years ago, ARK 2 was still a running, fully equipped, and viable shelter. Recently, however, it has fallen into disrepair as the generators failed; many of them require thousands of dollars in repairs, money that Beach and his supporters don’t have. Beach originally envisioned a shelter that could house a few thousand people, but eventually scaled it down to about 500 because of size and power restrictions. The shelter was created to “support refugees and support people,” in the event of a nuclear apocalypse, Beach says. “The concern here is survival and the reconstruction of society.”

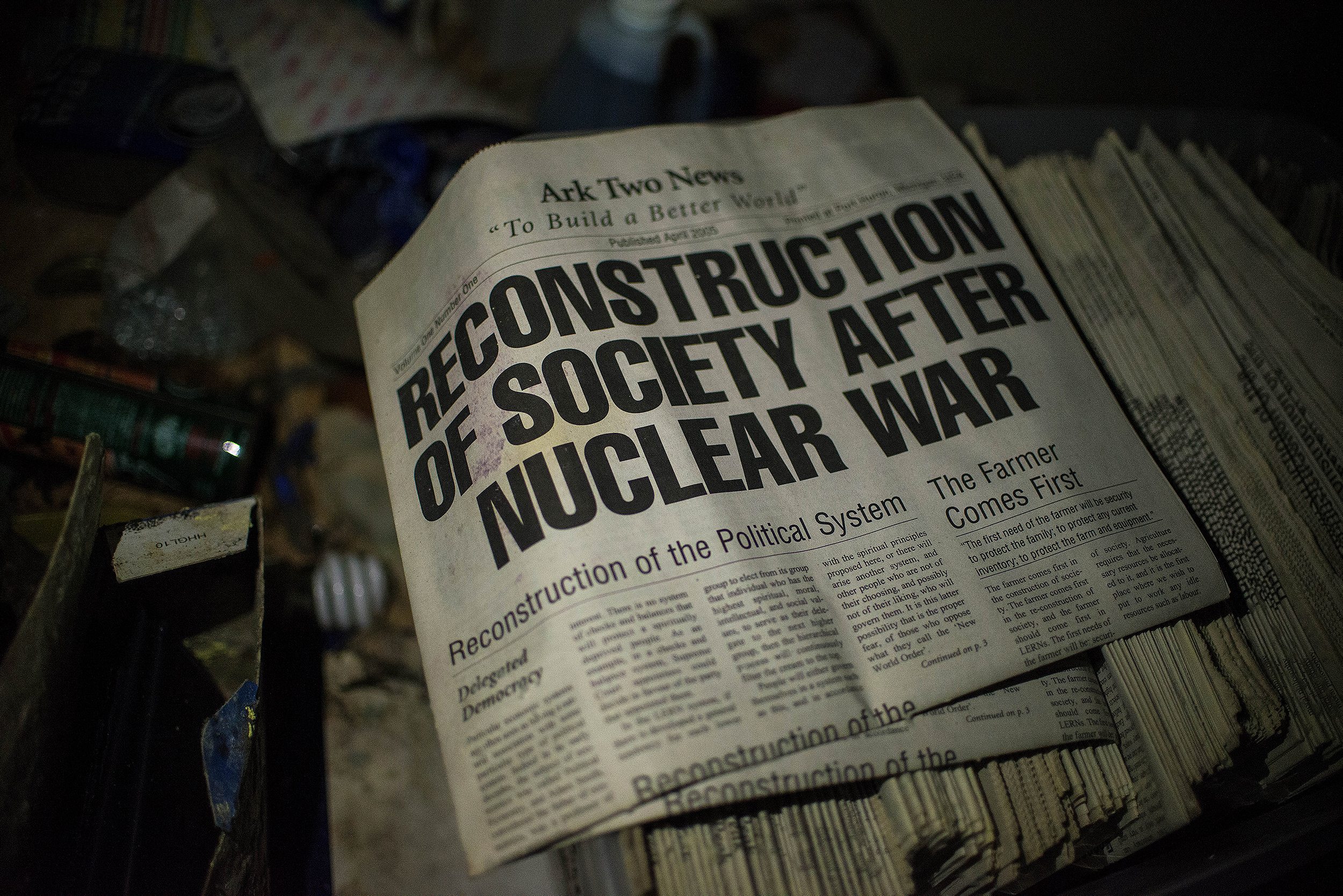

At the dawn of the new millennium, Beach and his followers wrote and distributed full broadsheet newspapers. Sample topics: how to use advanced radio communications (ARK 2 has such a powerful radio signal that it can reach about 300 miles), the importance of the farmer in the post-nuclear war society, and a range of other instructions that could be handed out and easily distributed among the survivors.

Beach believed ARK 2 would act as a central hub and shelter for reconstruction and redistribution of supplies. The shelter includes huge storage and distribution docks that flank the green entrance and blast door and would be “used to send off to other refugee stations,” he says. “You can back two semi trucks up to here, load on what you need, and off you go.”

The early spring grasses have begun to pop up through the brown mat of dead leaves, and the waterfalls in the ravine can be heard as we walk through the aboveground compound. Beach points out the multiple air intakes and vent shafts, essential when 500 humans are all breathing the same air in a confined space below. He points out the mortuary, tucked into the backside of the main entrance. We walk past a single rusted metal cylinder, about 15 feet in diameter—the very uncomfortable looking brig, or prison.

Beach reiterates that he believes the “crash” is coming “within weeks.” Beach and his supporters view every issue, every war, and every socio-cultural clash, as the harbinger of the end. He and his wife send out weekly emails and online newsletters to the hundreds of followers and supporters throughout North America, detailing Beach’s prediction of when things will go sour.

Beach’s newsletters outline his many predictions for “the crash.” Although he mentions the possible oncoming of a third world war, his current focus on an potential economic collapse, a topic he frequently addresses during our outing. “I keep saying, ‘Where is that economic/financial/monetary crisis?’ Everything seems the same one day to the next. I thought it would happen long ago. Everything is in place for it to happen… The trigger will probably be something we don’t imagine, but it will be sudden. That is the way catastrophes are.”

Beach comes to a halt, quietly panting in the mid-day heat. He sits down on a crusty, grass covered ventilation shaft and complains about the changes forced upon him and his bunker in recent years. Local officials “come in and always ask for something new. ‘Put a fence up! Kids might fall in.’ So we put a fence up. They come back, ‘Cover up the vent shafts.’ So we cover up the vent shafts. It’s a never ending struggle with the local authorities.” (Despite Beach’s objections, in its current state ARK 2 clearly presents some ongoing health and safety issues.)

In fact, most local authorities want ARK 2 filled in and sealed. Many have felt this way since it was first put in the ground. Yet others in the community like Beach and the odd buzz his shelter has brought to the region. In the words of one local councilor: “Let the man have it. As long as he isn’t hurting anyone, what’s the problem?”

Our tour is at an end. Before we leave, Beach reminds me of the myriad dangers that exist outside the ark. “We have more missiles now, greater conflict now, more countries have nuclear weapons,” he says. “Things are a lot more dangerous now than they were” when he first began building shelters.

We look out beyond ARK 2 to the idyllic landscape of rural Ontario, where, thankfully, the Apocalypse has yet to come.

Laura Babyn contributed reporting.