As basketball rises in popularity in Bolivia, teams are recruiting American players who have to learn a new language and overcome altitude sickness.

Travis Dupree comes from Eastman, a small town in central Georgia. He played basketball at Voorhees College in South Carolina but after graduation, found himself with no opportunities to play professionally. So like a lot of players in his position, he went to play abroad. But Dupree landed in an unlikely spot: Bolivia.

Dupree is the first American player to join the Liga Boliviana de Basquet, which was created by the Bolivian Basketball Federation in 2014. He plays for the Pueblito Nets, a team started by a group of amateur players that has slowly been climbing the ranks of Bolivian basketball since 2011. Today, the Nets are in second division. They finished the first season of the Liga Boliviana de Basquet in third place.

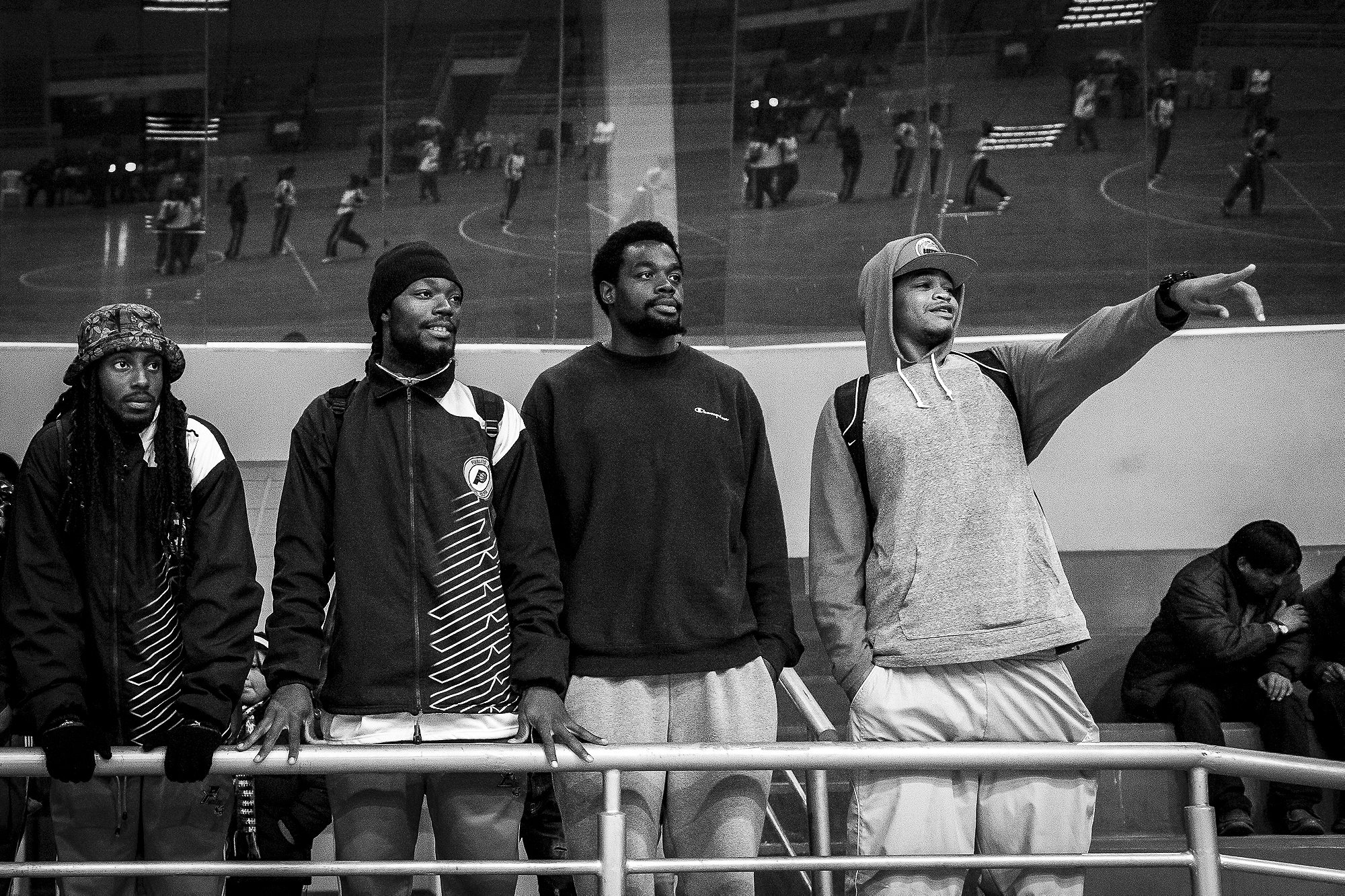

Dupree was recruited by the team’s founder, Carlos Mamani aka Pueblito, who is also the coach and the manager of the team, in 2014. Soon after, two other Americans followed his path: Domonick Steverson from Woodland, Georgia and Tadavius Williams from Moss Point, Mississippi. Other teams followed Mamani’s example. At the moment, at least eight Americans are playing basketball professionally in the Potosí region alone.

Adapting to their new home hasn’t been easy. The first challenge is the altitude; perched at 13,420 feet, Potosí is one of the highest cities in the world. Dupree says he was sick for two weeks when he arrived and lost 30 pounds. “It’s really hard to do anything,” says Georgia-born Rory Miller, who came on a month-long contract to help the Pichincha team toward the end of the season. “I really don’t like the high altitude, I can’t even breathe properly and no one told me about it.” The American players make around $1200 per month.

Cultural differences are also present on the court. “The referees allow a lot,” says DeQuan Massey, a player from New York. “I don’t know the language. I can’t really talk to them, so it’s hard.” Rory Miller agrees. “You can be hit in the face, thrown to the floor and the referees really don’t care. They protect the Bolivian players.”

Bolivian ball, it turns out, has a style distinct from U.S. basketball. More teamwork, more dribbling, fewer layup drills at practice. And, initially, lots of passing the ball to Dupree and the others and then watching them shoot. “At beginning it was hard,” says Dupree. “They used to pass the ball to the Americans and wait for us to score. Now it’s a bit different, but still they love to see us dunk. No Bolivians dunk.”

These skills are in part why, in Potosí, the American players have achieved a certain celebrity status. As African-Americans they stand out—there are Afro-Bolivians, but they are a vanishingly small part of the country’s population. And as basketball players, these men are also much taller than the rest of the population. I met them in a restaurant in Potosí, while I was having dinner. They caught my attention and I started following them. Though many of them see their time here as brief, some, like Dupree, are in it for the long haul. The 26-year-old is hoping for a long career, right here, in the Bolivian league.