After working as a correspondent in Africa, a British writer discovers an album of photographs mysteriously taken in Sierra Leone during the 19th century.

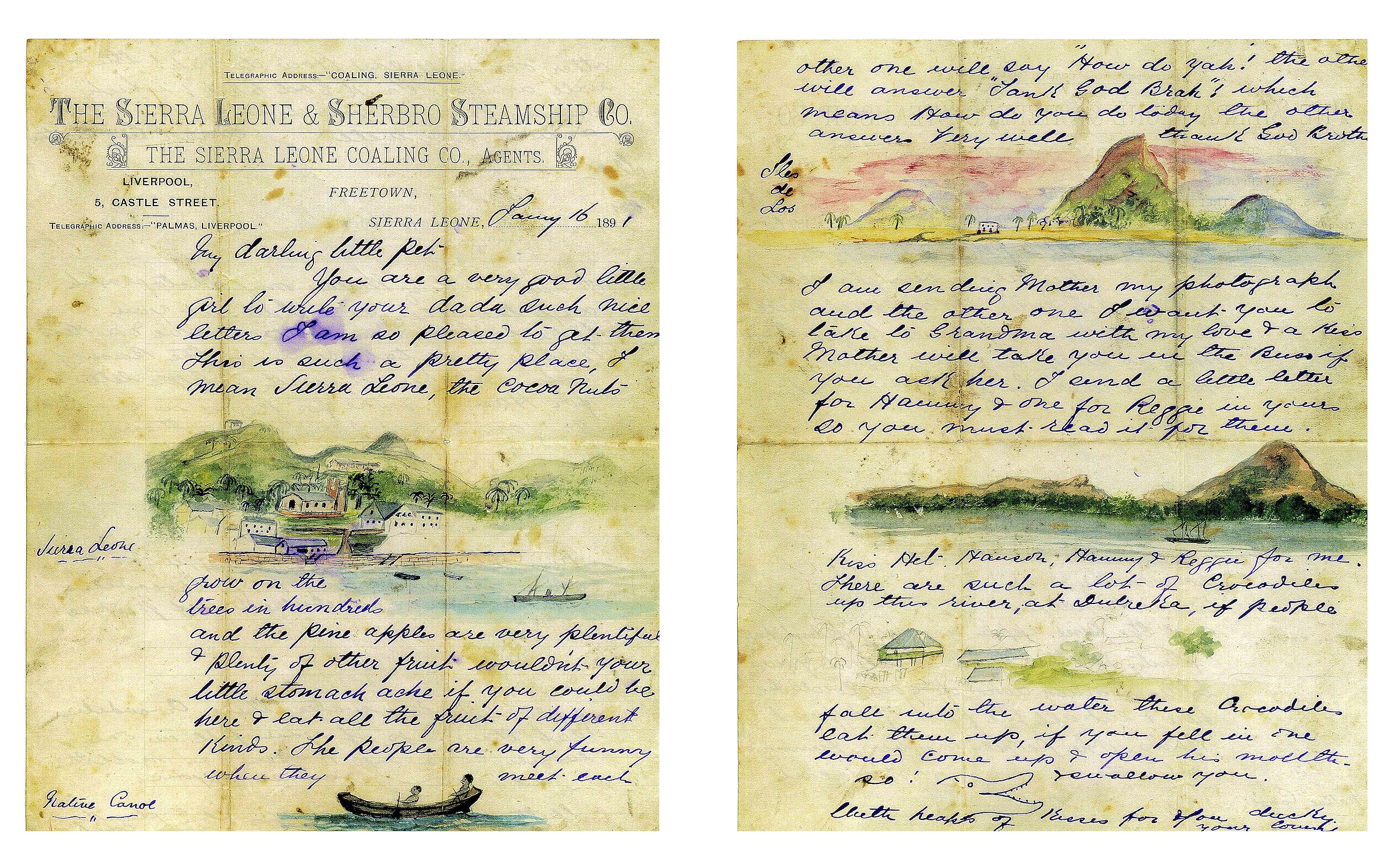

On a wet day last year I took a bus to Joppa, an eastern suburb of Scotland’s capital Edinburgh. I had traveled north from London to meet a woman called Barbara Hilliam, an artist whose work includes illustrations for Eleanor Catton’s Booker Prize-winning novel The Luminaries.

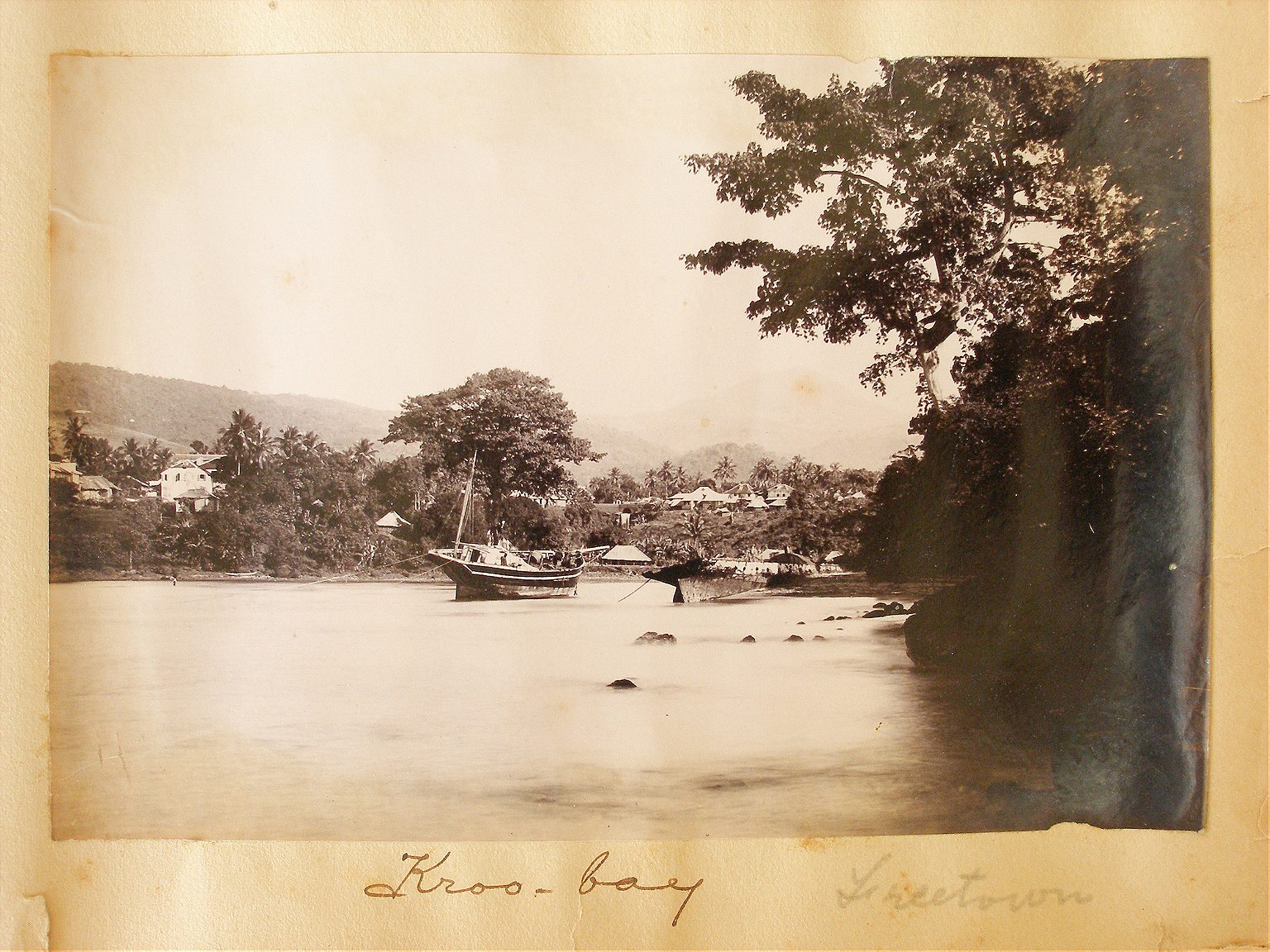

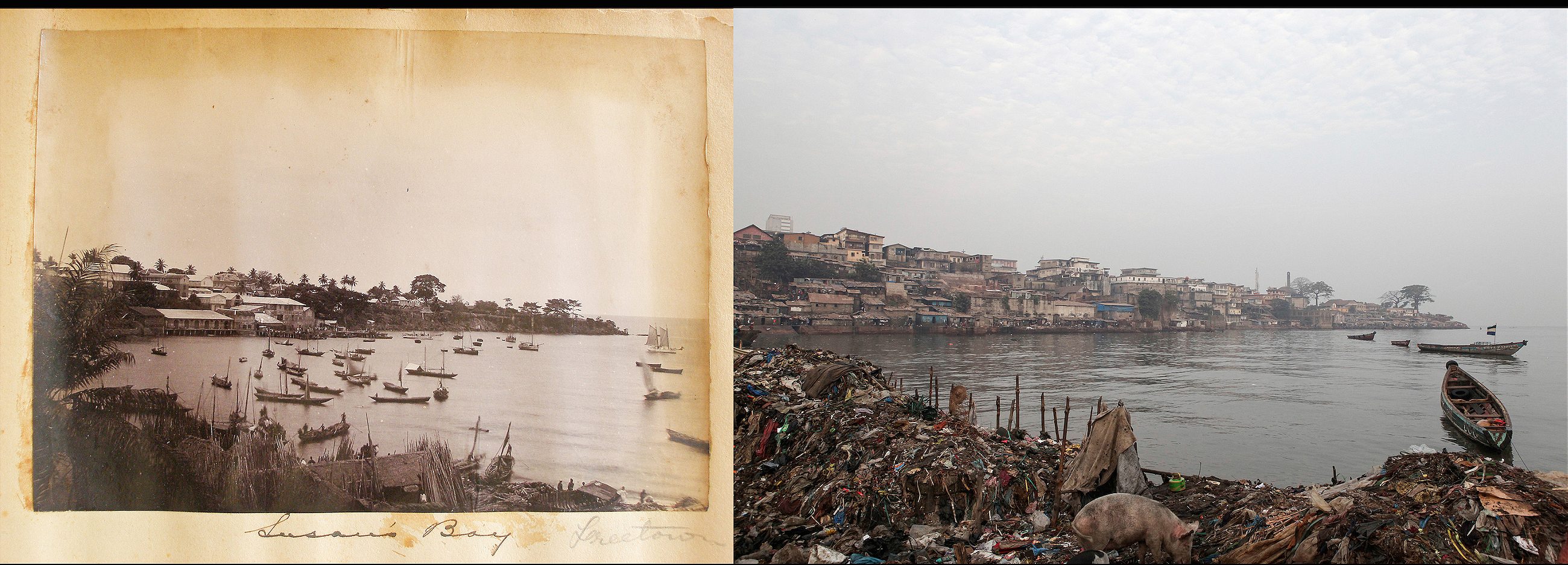

Hilliam and I had previously corresponded for almost two years. In 2010, I moved to Sierra Leone, a small country in West Africa that spent much of the 1990s convulsed by war, to work as a correspondent for Reuters and the Economist. The following year, I wrote a story about Kroo Bay, a slum in the capital Freetown. Hilliam saw the story and reached out to me by email. She explained that she had inherited an album of photographs of Sierra Leone taken in the late nineteenth century by her great-grandfather George Alfred Williams. One of the images in the album was labelled Kroo Bay. It showed a bucolic tropical cove hemmed with greenery, a dramatic contrast from the overcrowded shanty I had visited.

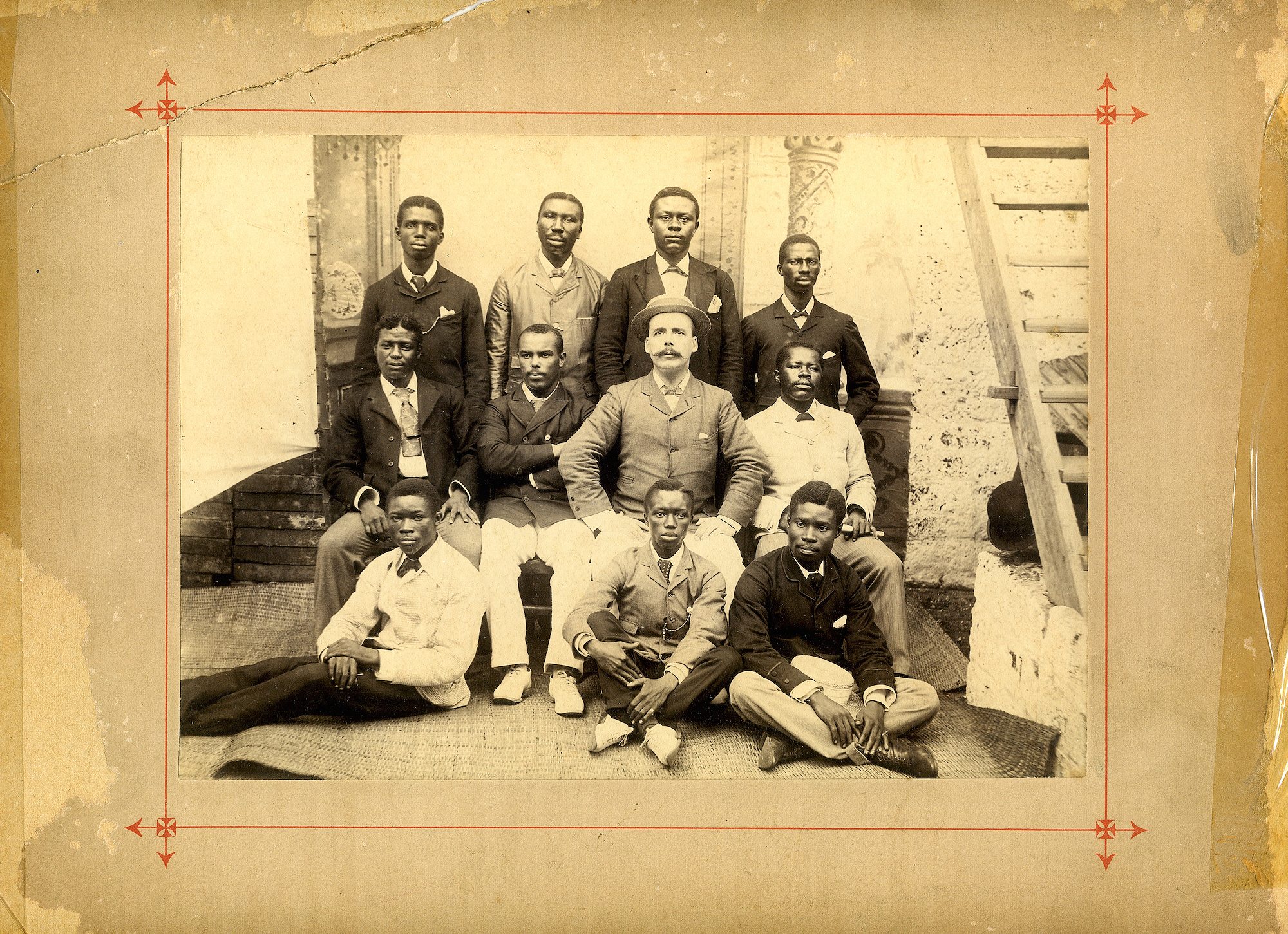

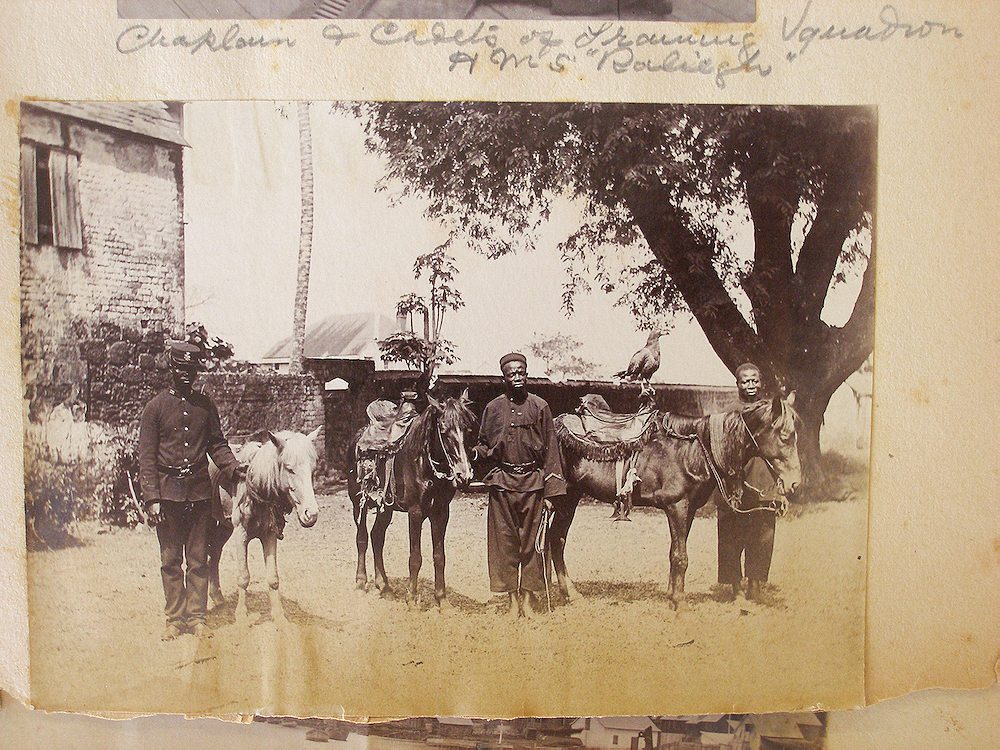

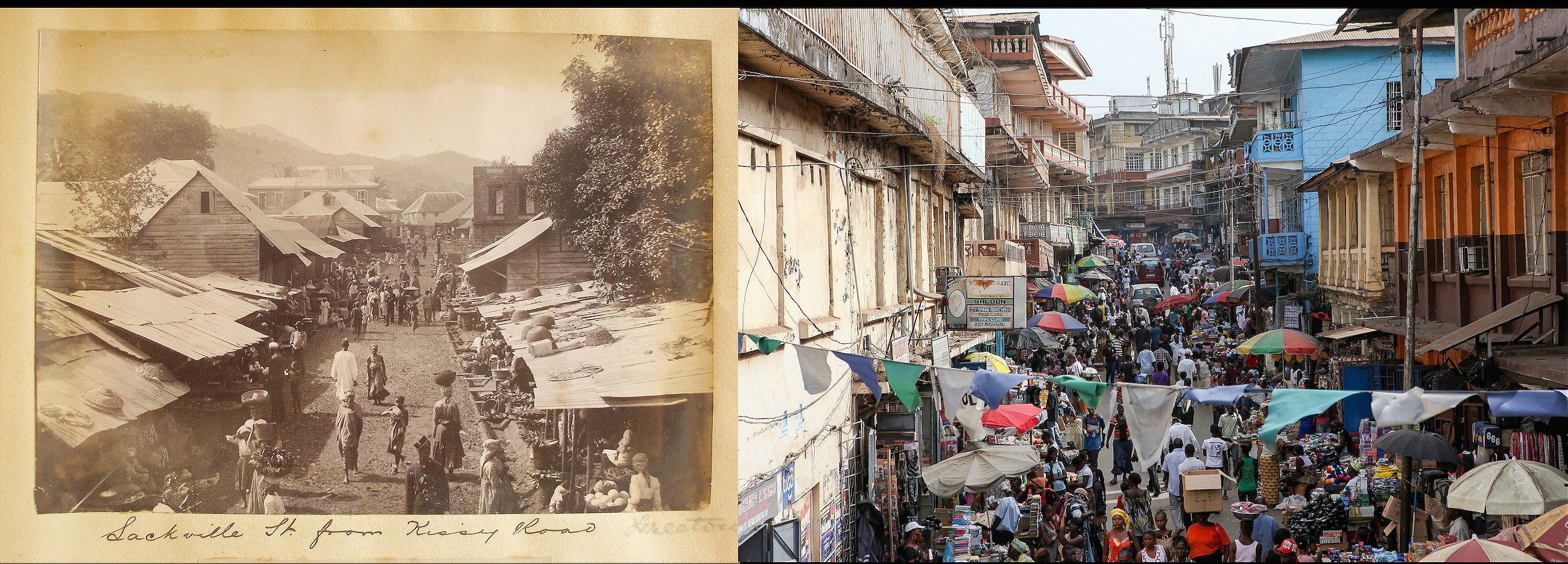

Hilliam sent over digital versions of other photographs. They amazed me. I knew Sierra Leone as a place of bright colors and a dark past, friendly people and shaky infrastructure. Freetown is vibrant but hectic, a city of manic traffic, crowding and noise. (The time I lived and worked there was before the Ebola outbreak that has brought such suffering to the country this year). Williams’ photographs, though, showed a wholly different world – British colonials in straw boaters and starched mustaches, sailing boats in the harbor, gas lamps in the streets.

The photographer’s story was extraordinary too. Williams worked in Sierra Leone as an agent for the Liverpool shipping line Elder Dempster. Around 1894, he became the consul for Sweden and Norway. And while imperialists were vying for power and influence in the region, he mounted an expedition to meet Alimamy Samory Touré, a war chief who was fighting against French colonization in West Africa. He lost 19 of his 300 ‘bearers’ to disease and skirmishes on the trip.

While so much had changed there were elements of Williams’ photographs that had survived in the Freetown I knew: a lighthouse here, a church there, the shape of a hillside over the water. With the help of a historian at Fourah Bay College, the oldest European-style university in West Africa, I was able to exactly identify a number of views. I re-photographed them, traversing the city with laminated prints of Williams’ photos kept in a spiral binder. Everywhere I went the local Sierra Leoneans were fascinated by this fragment of their past.

I spent something over two years in Africa. After I returned I wanted to meet Hilliam and see the album in person, so I made the journey north to Scotland. I was glad I did. As we sat her sitting room overlooking a wintry beach and the waters of the Firth of Forth I carefully turned ancient pages. It turned out Williams had covered more ground than I thought. There were images – in particular those of a large settlement – that I struggled to reconcile with Sierra Leone. Penciled captions in the album solved the mystery. Alongside Sierra Leone, Williams had also visited and photographed Ghana – then termed the Gold Coast and scene of the large settlement, Liberia and the Gambia.

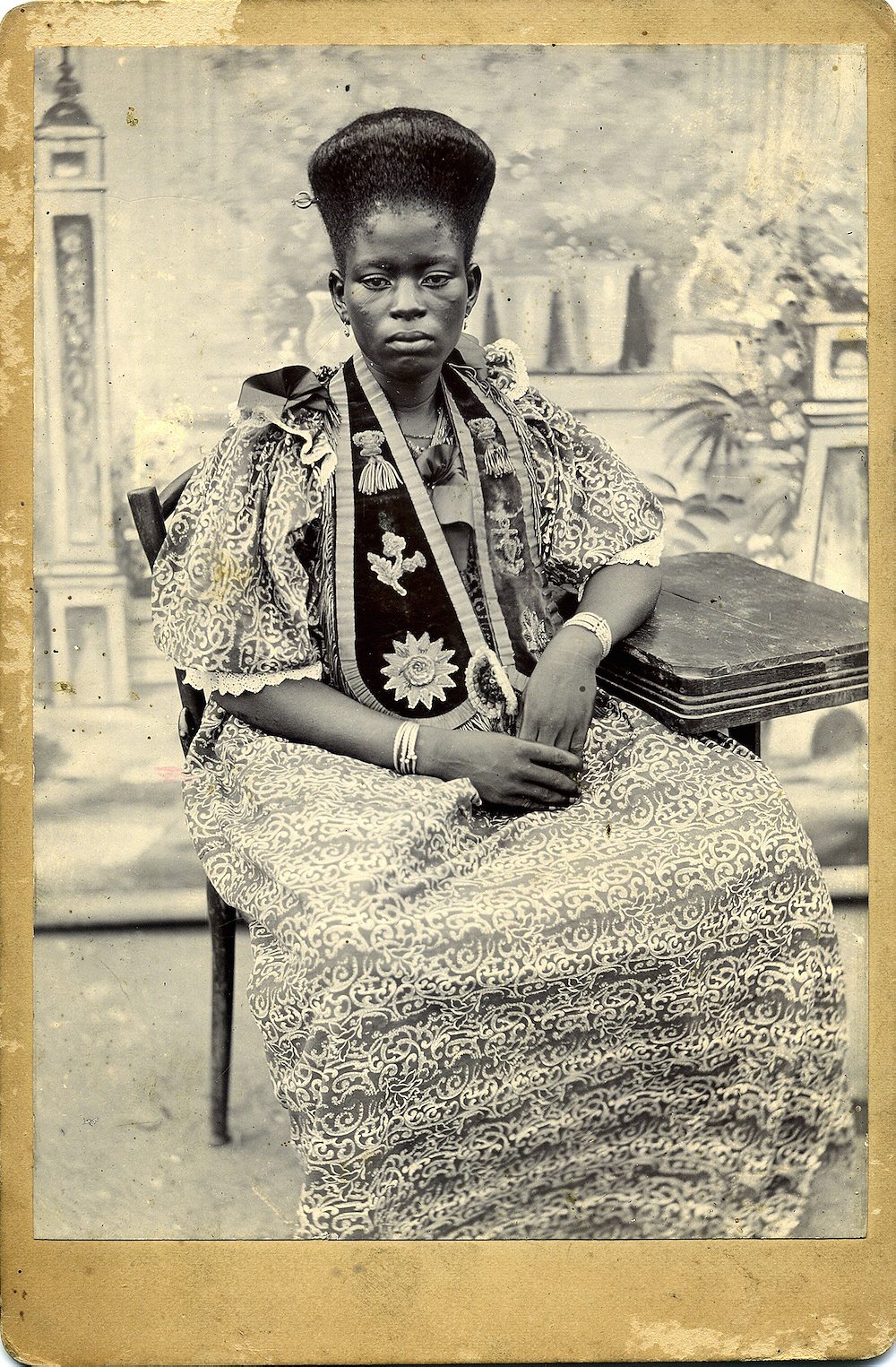

Most extraordinary were two images of his African butler and his wife. In one, a young man wears a quasi-Masonic outfit. In another, a girl with sad eyes has her hair arranged in an extraordinary vertical formation. Hilliam explained that by 1896, Williams had brought his African servants to England with him. They lived in his house in Southport outside Liverpool.

I wondered how those young West Africans felt, displaced so long ago to a cold northern clime. I also wondered about Williams himself. The longer I lived in Sierra Leone, the more I found the western expatriate community a curious and ultimately unsatisfying environment. Behind the hectic parties and bed-hopping lay considerable darkness. It seemed to me that many, perhaps myself included, were in Africa in flight from some element in their past lives; a failed relationship, their family, burdens of expectation.

“Mercenaries, missionaries, misfits,” quipped the older hands. I came back from Africa because I realized being there ultimately changes nothing; it is just geography, simply a place. It never really made anything better for anyone. As I looked at his old photography, I wondered what had driven George Alfred Williams there, so long ago when it was even more remote. We can never really know, but we can certainly wonder.