Jon Rosen travels to the Wagah border to witness the daily parade that marks the standoff between India and Pakistan

I should not have been surprised by the road sign—the green and white aluminum slab that hung across the highway and read Lahore: 30km.

I knew we were close to Pakistan, but the fields of wheat that stretched to the horizon did little to suggest we were approaching a city of ten million people. It was a Saturday afternoon along the Grand Trunk Road from Amritsar and somewhere up ahead, past the cattle pens, cricket pitches, and wedding-goers swarming to Dream Land and Sun Star Palace, there was a border.

This was not just any border, but one whose creation in 1947 had led to hundreds of thousands of deaths, one of the largest mass migrations in human history, and more than six-decades of highly militarized contempt between what today are two nuclear powers. Since 1959, the India-Pakistan crossing at the Punjabi village of Wagah, where I was headed, has also been one of spectacle, famous for a daily ceremony known as Beating the Retreat—a show of inane yet belligerent antics in which goose-stepping Indian and Pakistani border guards, donning fan-shaped tufted hats, spend 45 minutes trying to out-kick, out-stomp, and generally out-perform the others, before lowering their respective flags and closing the border for the evening.

These theatrics have made Wagah a border crossing unlike any other since Checkpoint Charlie: the vast majority of visitors arrive not to stamp passports but to gawk at the line in the sand and its guards. For both countries, it is a 365-day-a-year national ritual, held at what is the only open road crossing along the 1,800-mile border between the two states. Although I had come in part for the entertainment, I also hoped these stomping men in silly hats might teach me something about the long-intractable India-Pakistan conflict.

Who wouldn’t be fascinated by borders? The lines on maps, the arbitrary way in which the earth is sliced for man’s objectives, the feeling you get from crossing that line into some place new—even when that place turns out to be not so different. Growing up, I had always gotten a rush out of crossing into a new US state, even if it just meant walking on an airport runway or convincing my parents to drive across a bridge so I could step for a moment on Illinois or South Carolina soil. Later, as my travels became more global, this fascination had led me to some of the world’s most distinctive border posts. While living in Rwanda, I had once walked a mile along a mud-strewn path between the two official crossings with the Congolese city of Goma—a border at the crux of one of Africa’s longest simmering conflicts that was demarcated by little more than a piece of string and a few sullen troops with AK-47s.

It was a far different experience along the most fortified border in the world, the 160-mile long “Demilitarized Zone” between North and South Korea, which is open to visitors at the Joint Security Area of Panmunjom. There, on a day trip from Seoul, I stood in a border-straddling conference room with a stone-faced, teenaged South Korean conscript, who guarded a door that opened north into the world’s most secretive state. Outside, 50 meters into Kim Jong-un’s North, a lone member of the Korean People’s Army watched us enter and exit the building through binoculars.

How different in Europe, a continent that is busily melting its internal borders. Two years earlier in Belgium, one border I had set off to explore had failed to appear at all. One day, while visiting a girlfriend in the university town Leuven, I decided to run the sixteen miles round trip to the border between the Dutch-speaking region of Flanders and the French-speaking region of Wallonia—a line that effectively divides two nations within a state that has at times appeared on the brink of splitting apart. Having carefully planned my route on Google Maps, I arrived in an hour to the spot where the border should have been—somewhere along a quiet country road between the Flemish village of Sint-Joris Weert and the Wallonian village of Nethen. Lacking GPS to confirm my location, with no visible border crossing in sight, I approached the only other pedestrian, clearly a local, and asked whether we were in Flanders or Wallonia.

“J’sais pas,” he said in French, seemingly perplexed as to why I cared. “Wallonia is that way,” he pointed ahead. “Flanders is back where you came from.”

That we live in a world of borders at all is largely an accident of history. For the vast majority of human existence, whether in bands of hunter-gatherers, tribes of agriculturalists, or as subjects of great empires, the link between territory and sovereignty has been tenuous. Only at the Peace of Augsburg, signed in 1555 between warring Christian factions within the Holy Roman Empire, did the modern idea of borders begin to emerge. There, in an attempt to end a series of gory religious conflicts that had spread across much of Europe, negotiating parties agreed upon the formula cuius regio, eius religio (“Whose realm, his religion”). This granted princes within the Empire the authority to choose Catholicism or Lutheranism as the religion of those inhabiting the territory under their rule, thus establishing a link between political authority and the division of land.

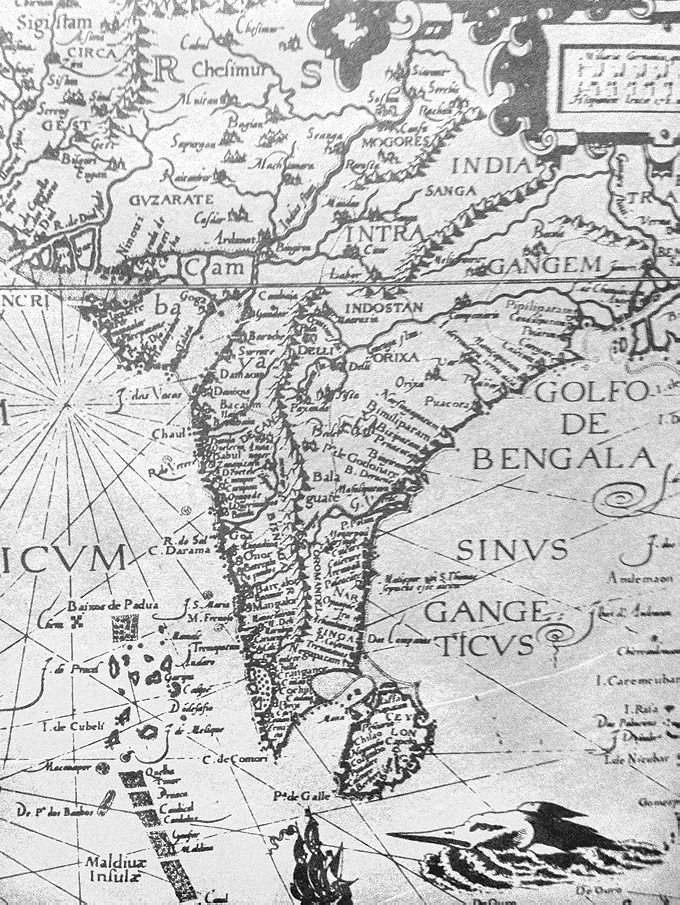

It was not until the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, after another century of European bloodletting, that the principle of Augsburg began to take hold. Under the Westphalian formula, as the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman has written, “rulers were entitled to impose laws that would override the choices made individually by their subjects, including the choice of god they ought to believe in and worship.” As Bauman explains, this model provided the foundations for the modern idea of the nation state, which was gradually “naturalized” in Europe, and subsequently imposed on the rest of the world by European colonial powers— often via crudely drawn boundaries dividing traditional tribal structures. Although emerging from the peculiar realities of 16th and 17th century Europe, “this historically composed pattern, chosen from many other conceivable ordering principles,” as Bauman writes, continues to define the contemporary international system.

For India and Pakistan, which were administered together under the British East India Company, and later the British Raj, division among Westphalian lines was never supposed to happen. In his book The Dust of Empire: The Race for Mastery in The Asian Heartland, journalist Karl E. Meyer argues that neither leaders of India’s twin independence movements, the Muslim League and the Hindu-dominated Indian National Congress, supported the idea of religious-based partition. Despite the subcontinent’s religious, linguistic, and cultural diversity, Congress’ mentor Mahatma Gandhi had said that India was still one nation, born of the great Mughal Empire, of Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians “drinking the same water, breathing the same air, and deriving sustenance from the same soil.” Even Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the secular-minded leader of the Muslim League, envisioned a united, confederal India consisting of Muslim and Hindu “nations,” rather than a separate Muslim Pakistan. With Muslim League and Congress leaders unable to agree on such a formula, however, Jinnah ultimately pushed for partition, fearing subjugation under a Hindu-majority central government.

What followed was a manifestation of the Westphalian model at its worst. Accepting the inevitability of partition, and seeking to get out of India as fast as possible, Britain’s last viceroy to India, Louis, Earl Mountbatten of Burma, set an independence date of August 15, 1947. He hastily established a boundary commission, led by British barrister Sir Cyril Radcliffe, to carve out the future Pakistan. Despite never having been to India, Radcliffe was given just 36 days to create not one boundary but two: a western frontier, dividing today’s Pakistani provinces of Punjab and Sindh from the Indian states of Punjab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat; and an eastern frontier, establishing East Pakistan, which would break away as Bangladesh following a 1971 war.

Despite the difficulty of the task—Radcliffe’s private secretary would later admit his boss had been “a bit flummoxed by the whole thing”—Radcliffe got to work, using a pile of maps, a 1943 census, and the assistance of two Hindu and two Muslim judges to best determine which areas should lie on the Muslim and non-Muslim sides of the border.

Although he finished the top-secret work on August 13th, violence caused by rumors and speculation led Mountbatten to delay the release of the final line until two days after rule of the Raj had ended, causing some towns to raise both flags at independence. When all was sorted, and the “Radcliffe Award” released, the uptake of violence was swift, particularly in the region of Punjab, now divided between India and Pakistan. “In and around Amritsar,” the historian Stanley Wolpert writes, “bands of armed Sikhs killed every Muslim they could find, while in and around Lahore, Muslim gangs—many of them ‘police’– sharpened their knives and emptied their guns at Hindus and Sikhs. Entire trainloads of refugees were gutted and turned into rolling coffins, funeral pyres on wheels, food for bloated vultures who darkened the skies over the Punjab.”

In all, ethnic and religious violence following partition left between 200,000 and one million dead, with more than 14 million resettling across Radcliffe’s borders.

During the next sixty-six years, the process of building nations out of the entities spawned by partition unfolded in a highly divergent manner. Today, east of the Wagah border sits a highly imperfect yet vibrantly democratic India; a state of myriad languages, ethnicities, religions, and castes that—for all its problems—has somehow crafted a robust sense of national identity. Although home to stark inequalities, periodic bouts of religious violence, and corruption in its rawest form, India is a country sufficiently cohesive that even the poorest citizens, as Walter Anderson, director of the South Asia Studies program at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, told me, “have faith that the system will somehow work to their benefit.” One reason for this, Anderson argues, was the use of democracy by India’s early leaders to unite a potentially fractious population—most notably through the granting of universal suffrage in India’s first constitution. “The leadership of the Congress was convinced it was necessary to unite the country, to give people a role in decision-making,” Anderson said. “I’d say the core reason for the Indian basis of integration is democratic institutions.”

To the west of Wagah sits a Pakistan where both democracy and identity are far more tenuous; a country routinely paralyzed by instability and Islamic extremism, where weak civilian governments have long played second fiddle to the military. This weekend’s election provided some evidence of hope for orderly civilian transitions, but even then millions of Ahmadis, to take one example, were disenfranchised. Many of the country’s woes, as the author Farzana Shaikh argues in her 2009 book Making Sense of Pakistan, can be directly linked to a crisis of identity that emerged following Pakistan’s partition. According to Shaikh, Pakistan’s birth as an entity rooted in opposition to Indian nationalism – and therefore defined by what it was “not” rather than what it was – has forever hindered the Pakistani sense of nation. Ultimately, she writes, this crisis of identity has “deepened the country’s divisions, blighted good governance and tempted political elites to use the language of Islam as a substitute for democratic legitimacy.” Moreover, she argues, Pakistan’s struggle to overcome this “negative identity” is at the core of its quest for military parity with India, a neighbor “almost seven times its size in population and more than four times its land mass.”

The Line of Control is not an official international border, but is nonetheless serious business.

Nowhere is this quest more visible than in Pakistan’s dispute with India over Kashmir, the strikingly beautiful Himalayan enclave that remains at the crux of the antagonism between the two states. The struggle over Kashmir, which was administered under the British Raj as a nominally independent Princely State, began at independence, when the Hindu ruler of Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh, wavered before joining India or Pakistan, hoping to somehow remain autonomous. In October 1947, however, a rebellion of Pashtun tribesmen forced Singh to seek Indian assistance in defense of the Kashmiri capital, Srinagar, which India provided only when the Singh agreed to cede the Muslim-majority territory to it. War broke out over Kashmir soon thereafter, and again in 1965, leading to the creation of another contentious border: the Line of Control dividing Indian-administered Jammu & Kashmir state from the Pakistan-administered territories of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan.

At 460 miles, 340 of which are paralleled by an India-built electric fence, the Line of Control is not an official international border, but is nonetheless serious business. For much of the 1990s, it effectively demarcated a war zone, as militants armed and trained by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) spy agency regularly launched attacks on Indian-held Kashmir, prompting a brutal Indian counter-insurgency and a conflict that resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and the exodus for most minority Hindus from the Kashmir Valley. Despite a 2003 ceasefire between the Indian government and Pakistan’s former military dictator Pervez Musharraf, the atmosphere in Kashmir, and along the Line of Control, remains tense. Here, along a frontier that splits villages and bisects mountains, there is no attempt at goose-step choreography. Instead, there is periodic violence, including a series of tit-for-tat attacks across the Line of Control that led to the deaths of one Pakistani and two Indian soldiers this January. According to Indian officials, Pakistani agents crossed the Line of Control, mutilated the bodies of the dead Indian soldiers, and carried the severed head of one back into Pakistan.

This same Line of Control is, in sections, a skiable border. Or at least, it’s surprisingly alpine. My first day in Srinagar, where I began my month-long trip to India, a friend and I spent an afternoon with a young shikara boatman, gliding on Dal Lake though reflections of Himalayan peaks. The second day, we headed to the ski resort of Gulmarg, in the Pir Panjal mountains to the west of the Kashmir Valley. Gulmarg is just a few miles from the Line of Control, and if it wasn’t just a week after the January skirmishes, and if I hadn’t been flopping around in the knee-deep powder to begin with, I would have contemplated skiing the backcountry to get there. Instead I thought I could just return to the hotel and look at a map, simply to relish how close we’d made it to the de-facto border. Yet when I loaded Google Maps, the dotted Line of Control I had seen back home was gone. As I would later learn, Indian law prohibits the publication of maps that are not in “conformity” with the official Survey of India, including those that fail to represent India’s claim to all of Kashmir. Although I could see plenty of Pakistan from the ski slopes—including the 26,660-foot Nanga Parbat, the world’s ninth-highest mountain— my border fix would have to wait for Wagah.

That day would come two weeks later, after a flight to Delhi and a bus trip north to the Punjabi city of Jalandhar, where I had stopped for a few days to visit a friend. There, on a Saturday morning in early February, I stood under a dusty highway exit ramp, breathing the fumes of India’s industrialization, and waited for a bus to Amritsar. The city is the spiritual center of the Sikh religion, and India’s closest to the Wagah crossing. Arriving 90 minutes later, I hopped a rickshaw to the colonial-era Grand Hotel, where I booked a ride to the Wagah ceremony for later in the afternoon. I spent the next few hours exploring the town, passing by the Harmandir Sahib, home to the holy scripture of Sikhism and better known as the Golden Temple, and the Jallianwala Bagh public garden, site of one of the darkest moments in Punjabi history. Here on an April afternoon in 1919, Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer ordered 50 British Indian Army riflemen to shoot at a peaceful civilian gathering in an event that would shock both the British government and leaders of the Indian resistance movement. With all entrances to the garden blocked, Dyer’s troops fired on the protesters for a full ten minutes— including women, children, and the elderly— spending 1,650 rounds and stopping only when ammunition was nearly exhausted. According to the Indian National Congress, the number of dead approached 1,000.

I returned to the Grand Hotel, hopped in a van with a group of Western travelers, and headed west, past the wedding goers and wheat fields, toward Pakistan. Twenty minutes later, not long after passing the Lahore road sign, our diver pulled over and parked in a field, as we alighted to a swarm of vendors hawking popcorn, chaat, and plastic Indian flags, much like the atmosphere outside of a stadium. Twenty rupee flag in hand, I walked toward the border with a stream of Indian and foreign spectators, arriving at a concrete grandstand as a festively plumed member of India’s Border Security Force (BSF) checked my passport. As a foreigner, I was assigned to the VIP section—somewhat closer to the action, yet far less raucous than the already brimming grandstand, which came to life as flag-bearing men in track-suits initiated the wave, and the high-wattage speakers unleashed a flurry of popular Hindi film songs including the Slumdog Millionaire hit Jai Ho. Glancing at the crowd, my eyes fixed on an artist’s rendition of Gandhi, painted in traditional white shawl, that was perched atop an archway that spanned the two-lane highway. A hundred meters away, across an iron fence in Pakistan, a stern-looking Jinnah, depicted in trademark Karakul hat, stared back.

What followed was a spectacle much like I had imagined. For 45 minutes, the stretch of road in front of me became a theater for all manners of stomps, kicks, steps, thrusts and marches. There were ordered salutes, peacock-like struts and seemingly crotch-defying knee-to-nose maneuvers, made all the more impressive by the advanced age (many appeared to be in their forties) of the BSF performers. Although the two sides agreed in 2010 to tone down some offensive gestures, including “thumb showing” and “staring,” the expressions of the guards were as stern as those I had witnessed at Korea’s Panmunjom, and the posturing of both India’s khaki-clad BSF and Pakistan’s black-clad Sutlej Rangers suggested something more odious than high-stepping pageantry. The only significant difference between the two sides appeared to be the role of women. In Pakistan, the performers are all male and female spectators sit separately in the grandstand. In India, seating is integrated and, since 2010, women have been part of the performance. However, as one BSF officer told local media in 2010, they are only allowed to continue the “very hard job” if they “feel comfortable and don’t receive any injury.”

At Wagah, though, the crowds are as much a part of the show as the troops. For the thousands on the Indian side, the patriotism was a living, firebreathing thing. Young and old from all religions, castes, ethnicities and walks of life meshed to create a frenzy unmatched by even the most high-stakes events in sport while launching into regular chants of Hindustan Zindabad, or “Hail India.” Although the Pakistani crowd was smaller, shouts of Pakistan Zindabad and the occasional Allah-o-Akbar taunted from underneath the green and white crescent moon flag across the border. The fervor reached a crescendo as both sides inched closer to the barrier, stomping more ferociously in one final bout of pent-up machismo before pausing for a bugle-accompanied lowering of both flags, the briefest of handshakes, and the slamming of the two gates.

When it was over, many in the crowd rushed onto the road to meet the performers, while others milled about, discussing the merits of a spectacle that, despite the overt belligerence, was clearly better than the Line of Control-style alternative.

“You don’t have your borders as bad as this?” one spectator— an auto parts dealer from the southern state of Tamil Nadu— joked as we walked back to our vehicles.

“We do some drama out here,” he smiled. “But we like it this way. At least at this level where they meet each other every day, you don’t expect them to start taking a gun and shooting at each other. As long as it stops with this, let’s all be happy.”

Back at the Grand Hotel in Amritsar, over Kingfisher beers and Punjabi butter chicken, I tried to make sense of the bizarre intensity of the scene I had witnessed. What was it about this rivalry—between entities divided by such an arbitrary line—that elicited such passion? I kept returning to the portraits of Gandhi and Jinnah, icons of the independence struggle, which gazed over the Wagah crowd like fathers watching over their children. Perhaps it was something about these men—and their visions for India and Pakistan—that was behind this show of patriotism.

Yet something about this reasoning did not seem right. Where, after all, was Gandhi’s India of agrarian self-sufficiency in today’s emerging industrial powerhouse? Where was Jinnah’s secular Pakistan in a country where security forces mingle with jihadists and political elites trade accusations of Islamic impurity?

“The irony is that those are jest images,” Johns Hopkins’ Anderson told me a few weeks later. “Jinnah’s views and Gandhi’s views have almost been forgotten in both countries. Gandhian philosophy and Gandhian economics have no following. Jinnah’s views of secularism in Pakistan have remarkably little following, either. Jinnah was a person who barely could speak Urdu, who drank, who ate pork, never went to a mosque, was probably an agnostic at best… he would be horrified with what he would see today in Pakistan.”

What if the two sides needed this conflict for the sake of building nations?

If the fervor were not about these icons, then, what if it were about something even simpler? What if Pakistan’s “negative identity,”—its birth as a response to “Brahman chauvinism and arrogance,” as Ayub Khan, Pakistan’s second president, wrote in his autobiography—gave ordinary Pakistanis a raison d’être, a source of pride? And what if Indians, despite India’s stronger basis of national integration, also needed Pakistan, that ever present thorn in India’s side, to fully embrace their Indian identity? Maybe, despite the bloody legacy of partition, the history of atrocities in Kashmir, the attacks by Pakistan-supported militants and counter-abuses by the Indian army, the two sides needed this conflict for the sake of building nations, for the sake of forging unity. And maybe, throughout this whole process, these entities divided by a highly artificial border had somehow come to justify that division; to bring the Radcliffe line to life, to give the Wagah crossing its meaning.

I washed down my second Kingfisher and passed through the hotel lobby on my way out to catch the night’s last train to Jalandhar. There, I paused to chat with Kuldeep Singh, a Grand Hotel employee who’d given me a primer on the ceremony that day and was eager to hear what I had thought of it. As we talked, I asked Singh—who told me he’d been to Wagah 30 times—if he had any reliable attendance estimates.

“Yes sir,” he replied, grabbing a pen to jot the numbers in my notebook. “The Indian side averages 25,000 spectators each day. Pakistan normally gets 200 or 300.”

Laughing, I almost began to argue. Sure, the Indian crowd I had seen was substantially larger than Pakistan’s. Perhaps by a factor of five. But certainly not a factor of 100.

But then I realized, this wasn’t about the facts. Forging a nation from arbitrary lines on a map requires more than that: both an embrace of the collective ‘us’ and a rejection of the collective ‘them’ that necessitates the bending of truth, be it exaggerating a few numbers, or celebrating historical icons, even if their views have largely been forgotten.

So instead of arguing over his figures, instead of telling him I felt the whole ceremony was a tad on the silly side, that I had actually been more affected by the no-nonsense, goose-step free glowering of Korea’s Panmunjom, I played along.

“You’re right,” I said. “The Indian side was crazy. I still cannot believe how high those guards could kick.”

Singh smiled.

“But what’s the deal with those Pakistanis?” I continued. “Man, their side was empty. Don’t they love their country?”